Soldiers of the Texas Brigade

Putting this series together has been enjoyable but also frustrating. None of the retrospective literature created by soldiers in the ranks made the cut, including classics such as Carlton McCarthy’s Detailed Minutiae of Soldier Life in the Army of Northern Virginia, 1861–1865 (1882) and John O. Casler’s Four Years in the Stonewall Brigade (1893). But so it goes with efforts such as mine. These final three books include a chaplain’s account from 1863, a Catholic priest’s voluminous diary, and a Marine lieutenant colonel’s novel published on the eve of World War II. Nicholas A. Davis’ The Campaign from Texas to Maryland was published in 1863 and reprinted with annotations by Donald E. Everett as Chaplain Davis and Hood’s Texas Brigade (Principia Press of Trinity University, 1962; paperback, LSU Press, 1999). Chaplain of the 4th Texas Infantry, Davis relied on his extensive

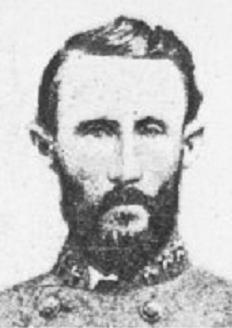

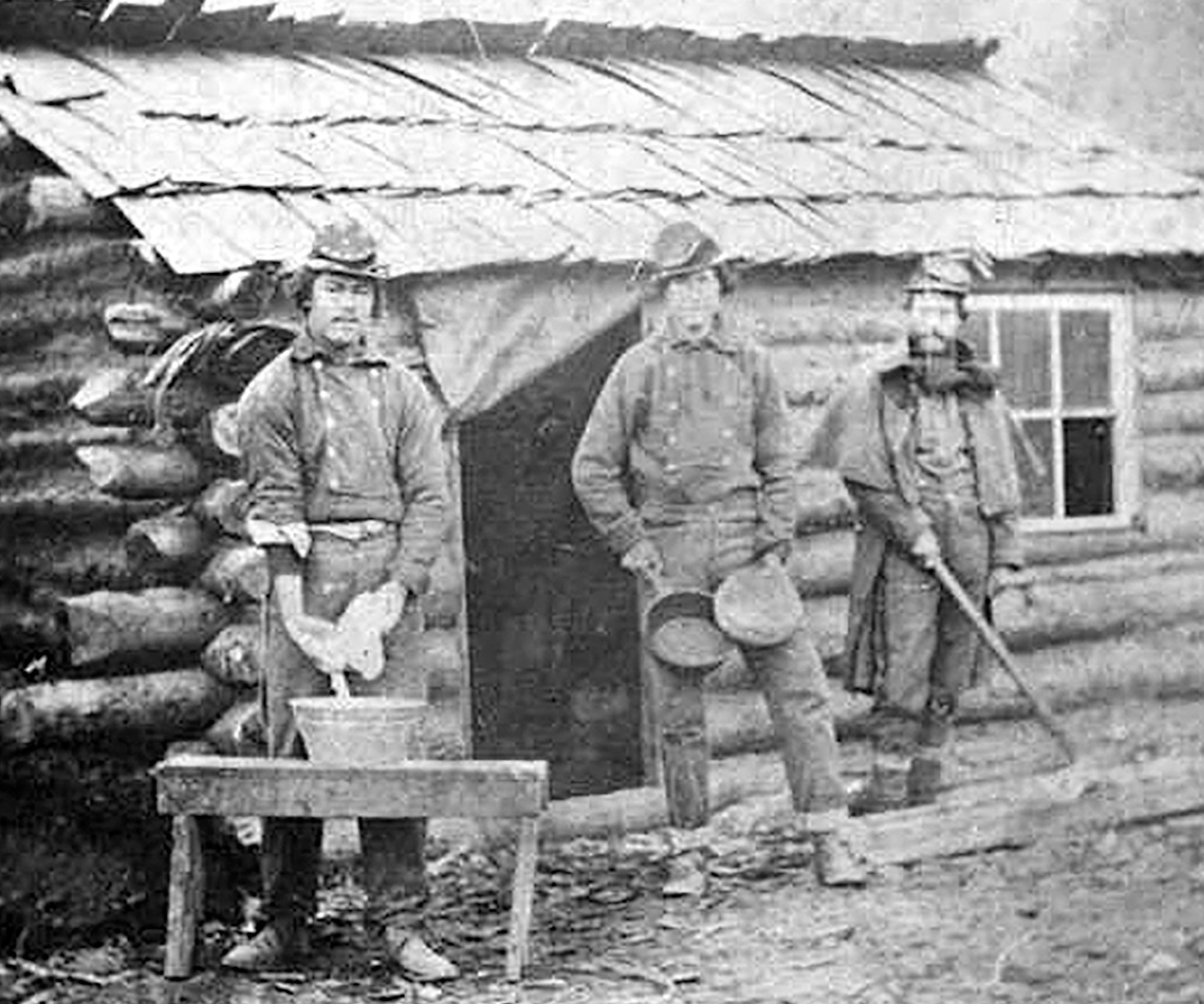

diary, other contemporary documents, and newspapers to produce a history covering the first 18 months of the Civil War. He chronicles incidents from Eltham’s Landing through the Battle of Fredericksburg in a narrative supplemented by biographical sketches of officers, a roster of the 4th Texas, and names of the brigade’s killed and wounded. Davis allocates considerable attention to the period before the regiment’s first combat, including the rough transition from citizen to soldier. “[W]e had the first realization,” he notes, “of the fact that we were actual soldiers, and … that a soldier must be patient under wrong, and that he is remediless under injustice—that he … is but the victim of all official miscreants who choose to subject him to imposition.” A long sketch of John Bell Hood illuminates why the Kentucky-born officer proved so successful with the Texas Brigade. Physically, Hood stood out at “about six feet two inches high, with full broad chest, light hair and beard, blue eyes, and … gifted by nature with a voice that can be heard in the storm of battle.” Davis pronounces him “as much admired and esteemed by the men under his command, as any General in the army.” Hood instilled strict discipline, which led to “his promotion in rank, and our success in battle. Its importance is admitted by all.” Only when “our people, our army and our Congress are willing to see it properly enforced,” writes Davis of Hood’s disciplinary standard, would Confederates “see our enemy beaten, our liberty won, and our country free.” Davis viewed the 1862 Maryland Campaign quite positively. He joined other Confederates who celebrated the capture of 12,500 Federals and immense materiel at Harpers Ferry and highlights George B. McClellan’s failure to pursue Robert E. Lee after the Battle of Antietam. “We had accomplished our object, as far as we were able,” he observes of the decision to withdraw to Virginia, “and, of course, were ready to return. Harper’s Ferry had fallen, and its rich prizes were ours.” Moreover, “Our march to and across the river was undisturbed—This, of itself, will show to the world the nature of McClellan’s victory…. [I]f he had beaten and driven us, as he publishes, why did he allow us to pass quietly away, after holding the field a whole day and night?” One long passage discusses “Abolitionist, Unionist, Federals or Yankees” as possible terms for the enemy. Davis reveals his deep sectional bias in settling on “Yankees,” a word that “has ever been used in contemptuous ridicule of their conduct towards each other, and their dealings with the rest of the world.” Correctly understood, he explains, “it means meddlesome, impudent, insolent, pompous, boastful, unkind, ungrateful, unjust, knavish, false, deceitful, cowardly, swindling, thieving, robbing, brutal and murderous.”

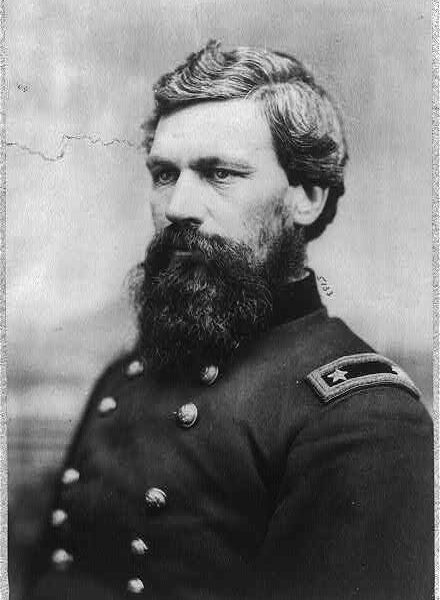

The Civil War Diary of Father James Sheeran: Confederate Chaplain and Redemptorist, edited by Patrick J. Hayes (Catholic University of America Press, 2016), covers operations from Second Bull Run through the 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign. The Irish-born Sheeran, who served with the 14th Louisiana Infantry in the Second Corps, comments frequently about “Stonewall” Jackson, Jubal Early, and other leading generals in the army, describes the natural and built environment, conveys details about battles and skirmishes, and provides valuable information about his religious work with the troops. Some of Sheeran’s passages dealing with combat and its aftermath anticipate realists such as Frank Wilkeson and Ambrose Bierce. On May 6, 1863, he surveyed carnage on the battlefield at Chancellorsville: “[Y]ou could see the dead bodies of the enemy lying in every direction, some with their heads shot off, some with their brains oozing out, … some with their noses shot away, … others with their bowels protruding, some cut in two with shells….” Worst of all, fires had swept through parts of the field “and for near half a mile burned the dead bodies and many of the wounded to a crisp.” An ardent Confederate, Sheeran expresses muted criticism of Lee during the retreat from Gettysburg. “We had penetrated the enemy’s country,” he notes on the evening of July 4, “and had an ample opportunity of retaliating on them for the cruel and barbarous manner in which their soldiers had treated our people. We had the capital of Pennsylvania at our mercy, but our general chose rather to meet the enemy on the battlefield and test by the fortunes of war our claims to independence.” The rain-soaked march away from Gettysburg also prompted far harsher comments about northern Protestants. “I thought too on this sad night of the great injuries Protestantism had done to society,” he laments, “by robbing man of a religious guide and leaving him a prey to his own wild passions and frantic imaginations. For were it not for this fanaticism of the demonical Abolitionists of New England, this unholy and murderous war should never have taken place.” Sheeran remained behind to minister to wounded soldiers after the Confederate defeat at Cedar Creek in 1864. On October 31, he recorded that “the Brute Sheridan and his servile cubs at the Provost office” determined to arrest him. While on the way to more than a month’s imprisonment, he combined sarcasm and anger in telling one of his captors that “the ‘liberators of the Valley’ were not satisfied with killing the bodies of their Catholic soldiers, but they wished also to damn their souls by depriving them of the help of their religion.” John W. Thomason Jr. brought combat experience and familiarity with Confederate veterans to the task of writing Lone Star Preacher: Being a Chronicle of the Acts of Praxiteles Swan, M.E. Church South, Sometime Captain, 5th Texas Regiment Confederate States Provisional Army (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1941).

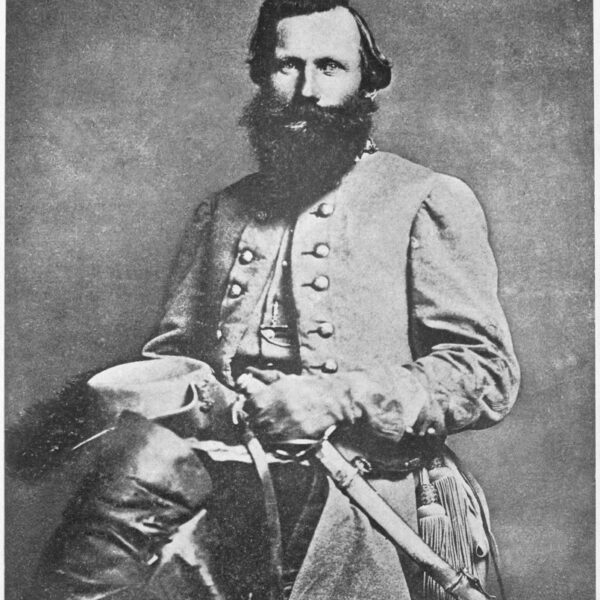

A grandson of Major Thomas J. Goree of James Longstreet’s staff, Thomason was awarded the Silver Star as a Marine in World War I. Historical characters inhabit his novel, among them Lee, Jackson, “Jeb” Stuart, and Hood of the army’s high command, as well as Major William “Howdy” Martin, an officer in the 5th Texas Infantry. For Praxiteles Swan, the novel’s fictional central figure, Thomason drew on “a combination of two distinguished early Methodist saints in Texas, with overtones from several godly and scholarly men of those days whose life span overlapped my own.” Thomason deployed his considerable artistic talent to create numerous sketches of individuals and episodes that enhanced the text. Both Lost Cause and reconciliationist themes emerge in Lone Star Preacher. The Confederate rank-and-file, drawn from very different parts of the South, did not compose “a really homogeneous army,” states Thomason in his foreword, but held in common “a belief in Southern rights.” “That one of those rights involved the dark institution of chattel slavery is not pertinent,” he insists in vintage Lost Cause style, “because few of them owned slaves, or hoped to own them.” As for reconciliation, the men’s “effectiveness in war” impressed their opponents and left a legacy of “valor and devotion … treasured by a united country.” A grandson of a soldier in the 20th Maine Infantry had served as Thomason’s “adjutant the last two years, and we are proud, both of us, of the fight our people made on Little Round Top…. And perhaps better marines for it.” I selected Lone Star Preacher, the only nonparticipant’s voice, because of Thomason’s ability to evoke the military culture of the Army of Northern Virginia and to narrate battle’s chaos. An incident late in the war got at the powerful bond among soldiers from individual units. Rumors reached the Texas Brigade that, because of attrition, it might be combined with other diminished commands. Martin and Swan seek out Jefferson Davis in Richmond to argue against the proposal. Martin passionately recites a list of the brigade’s great battles, followed by: “I tell you, Mr. President, we have left our dead on every field this army has fought—from the James River up into Pennsylvania—an’ as far west as north Georgia! And outside of a few boys who straggled too far forward at Gettysburg, we have buried our dead ourselves! (This was important to soldiers—it meant you held your ground.)” The brigade carried “battle flags that our women gave us … they air Texas Flags. Texas ladies made them. Texas boys have fought under them. Those names I named you, they air on those flags. Will you take ’em away from us, an’ give us a number in place of them?” Texans always obeyed orders, continues Martin, “‘But Mr. President, we air the Texas Brigade, an’ so we will remain’—He stopped talking and the silence fairly thundered. Then Praxiteles added quietly—‘That’s what the boys wanted you to know, Mr. President.’” Thomason’s handling of the brigade’s action at Antietam showcases his narrative skill. As the Texans approached D.R. Miller’s cornfield, “Hooker was storming with all his corps; batteries in line with his infantry; his men shouting in the deep-chested, rhythmic, Northern way.” The Texans, “not quite nine hundred bayonets, met them on the run, in the plowed field beyond the corn; there was a collision that shook the world, and Hooker recoiled from that place … but the Southern yell was mighty thin, and the musketry soon drowned it.” Amid “dust and thick smoke,” soldiers followed a routine: “Plunging forms appeared over your sights; you fired, drew cartridge, bit cartridge, poured the powder down the muzzle, plied your ramrod, capped your piece, fired, and did it over again.” The struggle intensified: “Men had grotesque black powder rings around their mouths. Men fired standing, to see over the smoke, or squatting, to see under it, or kneeled and fired straight into it…. The battle howled around their left and ran off across their front to the right, and away; Lee’s army was fighting for its life.” Thomason the novelist surely consulted some of the testimony discussed in “Voices From the Army of Northern Virginia.” So also have countless historians over more than a century. For foundational scholarly works, readers should consult Douglas Southall Freeman’s Lee’s Lieutenants: A Study in Command (3 vols., 1942–1944), still essential despite the author’s embrace of much Lost Cause orthodoxy, and Joseph T. Glatthaar’s General Lee’s Army: From Victory to Collapse (2008), a superb overview of the subject. For debates over memory and historiography, my own Lee and His Generals in War and Memory (1998) and Lee and His Army in Confederate History (2001) might prove useful. But for anyone hoping to understand the Confederacy’s preeminent army there is no substitute for the published primary testimony.

GARY W. GALLAGHER IS THE JOHN L. NAU III PROFESSOR OF HISTORY EMERITUS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA. HIS PUBLICATIONS INCLUDE THE ENDURING CIVIL WAR: REFLECTIONS ON THE GREAT AMERICAN CRISIS(LSU PRESS, 2020).

This article appeared in the Summer 2023 (Vol. 13, No. 2) of The Civil War Monitor.

Read other installments in this series:

Part 1: Foundational Works

Part 2: Artillerists

Part 3: European Observers

Part 4: Corps Commanders

Part 5: Division Commanders

Part 6: Managing the Cavalry

Part 7: Robert E. Lee