In a postwar illustration, Robert E. Lee is depicted leading his men at Gettysburg.

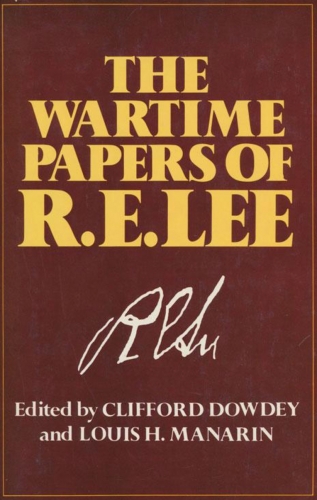

Three books containing Robert E. Lee’s testimony provide the foundation for any collection on the Army of Northern Virginia. Lee forged the army into a powerful military instrument, molded its culture of command, built an unrivaled bond with its rank-and-file, and, based on operational successes, saw it become the most important national institution in the Confederacy. This essay examines two volumes of his correspondence and a third that contains a series of postwar interviews with him. As a group, these books illuminate myriad elements of Lee’s tenure at the head of the army. Anyone seeking more information can go to the 128 volumes of the Official Records or to the Lee Family Digital Archive, sponsored by Stratford Hall, at leefamilyarchive.org. Clifford Dowdey and Louis H. Manarin edited the most important published collection of Lee material in The Wartime Papers of R.E. Lee (Little, Brown, 1961). They selected 1,006

items from an extant body of more than 6,000. “In his official correspondence, even in his most urgent messages on plans and needs,” the editors observe, “there is the guarded control of careful composition. In the letters he wrote to Mrs. Lee and his children, there is a casual candor about the larger events and the course of their fortunes in the simplicity of homey exchanges.” The editors give locations for all the documents but add no editorial notes, a regrettable decision likely aimed at keeping the book, which runs to almost 1,000 pages, at a reasonable size. Space limitations prevent a systematic review of the book, but two documents suggest its value. A letter to Secretary of War James A. Seddon dated January 10, 1863, reveals Lee’s visceral reaction to the Emancipation Proclamation. Lincoln had laid out “a savage and brutal policy,” Lee fumes, “which leaves us no alternative but success or degradation worse than death, if we would save the honor of our families from pollution, our social system from destruction….” Lee’s use of “degradation,” “pollution,” and “social system”—words white southerners often deployed when discussing the consequences of abolitionism—highlight the degree to which he believed Lincoln’s policy menaced more than the integrity of the Confederate political state. A second letter, written to Mrs. Lee on July 26, 1863, concerns Lee’s thoughts about Gettysburg. “The army has laboured hard, endured much & behaved nobly,” he affirms. “It has accomplished all that could be reasonably expected.” The soldiers “ought not to have been expected to have performed impossibilities,” Lee continues, “or to have fulfilled the anticipations of the thoughtless & unreasonable.” The last sentence can only be read as self-criticism, inasmuch as Lee himself asked Confederate infantry to win a contest marked by what he considered substandard performances from senior subordinates. Successful assaults at Gaines’ Mill, Second Bull Run, and Chancellorsville no doubt explain his reliance on the soldiers’ prowess. The letter also shows that he grasps the degree to which the Confederate populace had invested its hopes in the army. One important document in the book contains a crucial error. Lee’s letter to his brother Sidney Smith on April 20, 1861, has been quoted endlessly to explain why he resigned from the U.S. Army. The editors took their text from Robert E. Lee Jr.’s Recollections and Letters of General Robert E. Lee (1904), long the principal source for Lee’s family correspondence. In a key passage, Lee states that he had “wished to wait till the Ordinance of Secession should be acted on by the people of Virginia….” But the junior Lee had quietly edited the original. Lee actually wrote: “I wished to wait until the ordinance of revolution should be acted on by the people of Virginia….” Clearly, Lee’s son had softened the import of his father’s statement, portraying a constitutional, rather than a revolutionary, course of action.

Lee’s Dispatches: Unpublished Letters of General Robert E. Lee, C.S.A. to Jefferson Davis and the War Department of the Confederate States of America, 1862– 65, edited with elaborate notes by Douglas Southall Freeman (G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1915), presents 204 documents omitted from the Official Records. A new edition published in 1957, with a foreword by Grady McWhiney, adds 10 items but otherwise leaves the original text unchanged. Based on close investigation, Freeman concludes that the 204 letters and telegrams originated as “a file kept for his own reference by President Davis himself.” He further remarks that the documents “show … that relations between General Lee and President Davis never reached that degree of restraint that rendered frank confidence and full co-operation impossible.” In fact, they underscore the two men’s agreement on the primacy of national over state and local needs, a central element in their working relationship.

These documents feature many famous quotations associated with Lee. On July 12, 1864, for example, Davis solicited his opinion about John Bell Hood as a replacement for Joseph E. Johnston at the head of the Army of Tennessee (an indication that the president sought Lee’s advice about topics unrelated to the Army of Northern Virginia). Lee sent two responses. The first, a telegram, states bluntly: “It is a bad time to release the commander of an army situated as that of Tenne. We may lose Atlanta and the army too. Hood is a bold fighter. I am doubtful as to other qualities necessary.” The second response, less brusque but equally clear, reads: “Hood is a good fighter very industrious on the battle field, careless off & I have had no opportunity of judging of his action, when the whole responsibility rested upon him. I have a high opinion of his gallantry, earnestness & zeal. Genl [William J.] Hardee has more experience in managing an army.” Earlier that year, Lee had urged an all-out effort on the part of farmers from Virginia’s Northern Neck who complained about Union depredations. His comments highlight a belief, shared by Davis, that civilians should look to national needs even when coping with local problems. “The best way for the citizens of the Northern Neck to save their cattle grain bacon &c from these marauding parties,” insists Lee, “is to send them across the Rapp[ahannock] and sell them to the Confederate government.” Such a “proper combination & energy on the part of the citizens with what aid government agents can give would in this way save a great deal for the army & the people.” Lee never published anything about the war. Notes from a series of postwar conversations offer the clearest

expression of his thoughts about the conflict—though, admittedly, they are evidence once removed from the source. I decided to publish Lee the Soldier (University of Nebraska Press, 1995), which comprises an array of assessments of Lee’s generalship, in part to include the notes from his conversations with William Allan (former ordnance chief in the Second Corps), William Preston Johnston (General Albert Sidney Johnston’s oldest son and wartime aide to Jefferson Davis), and Edward Clifford Gordon (a Presbyterian minister and veteran of Lee’s army). The conversations at Washington College between 1868 and 1870 reveal Lee’s opinions about various lieutenants, policies adopted by the Richmond government, and the published writings of former Confederate officers. Sections on the 1862 Maryland Campaign and Gettysburg are especially enlightening. Lee twice mentions his support late in the war for enrolling enslaved men in the Confederate army and discusses his decision to resign from the U.S. Army in April 1861. Overall, the conversations shed light not only on Lee’s military operations but also on his postwar frame of mind. A few quotations will suggest the flavor of the conversations. On April 15, 1868, Lee spoke with Allan about Gettysburg. “First he did not intend to give general battle in Pa. if he could avoid it—” records Allan. “The South was too weak to carry on a war of invasion, and his offensive movements against the North were never intended except as parts of a defensive system.” With battle approaching, “He did not know the Federal army was at Gettysburg, could not believe it, as Stuart had been specially ordered to cover his (Lee’s) movement & keep him informed of the position of the enemy, & he (Stuart) had sent no word. He found himself engaged with the Federal army therefore, unexpectedly, and had to fight.” Once fighting began, “victory wd. have been won if he could have gotten one decided simultaneous attack on the whole line. This he tried his utmost to effect for three days, and failed.” In sum, “Stuart’s failure to carry out his instructions forced the battle of Gettysburg, & the imperfect, halting way in which his corps commanders (especially Ewell) fought the battle, gave victory, (which as he says trembled for 3 days in the balance) finally to the foe.” Lee told Allan why he eased Richard S. Ewell out of the army during the Overland Campaign. “On May 12 Lee found Ewell perfectly prostrated by the misfortune of the morning, and too much overwhelmed to be efficient,” Allan writes, “and on May 17 or 18 [actually, May 19] when E. went out on Grant’s flank, to attack, and did get into a corps or two of troops, he lost all presence of mind, and Lee found him prostrate on the ground, and declaring he cd not get [Robert E.] Rodes div. out. (Rodes being heavily engaged with the enemy.).” Lee remonstrated “that if he could not get him out, he (Lee) could.” Ewell’s moment of truth arrived later in the month: “Lee tried to put him off by sickness, but when E. insisted, he told him plainly he could not send him in command.” Robert E. Rodes “had come to Lee and protested against E’s being again placed in command…. [H]e (Lee) was very reluctant to displace him, but felt compelled to do so.” In a talk with Johnston on May 7, 1868, Lee “spoke of Grant’s gradual whirl and change of base from Fredericksburg to Port Royal, thence to York River and thence to James River, as a thing which, though foreseen, it was impossible to prevent.” Lee knew “this campaign had been compared by General Johnston to his re- treat from Dalton. ‘I do not propose to criticize him,’ said he, ‘but I fought the enemy at every step. I faced him and I protected Richmond. Stay-at-home critics may censure my army,’ he said, ‘but I believe I got out of them all that they could do or all that any men could do.’” The final voices in this series will be a Louisiana priest, a Texas chaplain, and a Marine lieutenant colonel turned novelist whose grandfather served on James Longstreet’s staff.

GARY W. GALLAGHER IS THE JOHN L. NAU III PROFESSOR OF HISTORY EMERITUS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA. HIS PUBLICATIONS INCLUDE THE ENDURING CIVIL WAR: REFLECTIONS ON THE GREAT AMERICAN CRISIS(LSU PRESS, 2020).

This article appeared in the Summer 2023 (Vol. 13, No. 2) of The Civil War Monitor.

Read other installments in this series:

Part 1: Foundational Works

Part 2: Artillerists

Part 3: European Observers

Part 4: Corps Commanders

Part 5: Division Commanders

Part 6: Managing the Cavalry

Related topics: Robert E. Lee