Confederate gunners fire at the enemy in a postwar illustration titled “The Artillery Duel.”

Artillerists created an invaluable body of evidence relating to the Army of Northern Virginia. Though they made up only about 7.5 percent of the army’s strength, they figured prominently in almost every battle and decisively in a few. Porter Alexander’s Fighting for the Confederacy, discussed in the first installment of this series, offers the best narrative by any gunner in the army, and Jennings C. Wise’s The Long Arm of Lee, published in two volumes in 1915 and later reprinted several times, is an essential title on Lee’s artillery. The latter, though marred by the author’s embrace of many Lost Cause arguments, nonetheless contains extensive information about ordnance, the evolution of the artillery’s organization, tactical details at major battles, and battery and battalion commanders. The three books in this essay include a set of letters and a memoir written by two officers who led battalions and the diary of a private in a Virginia battery.

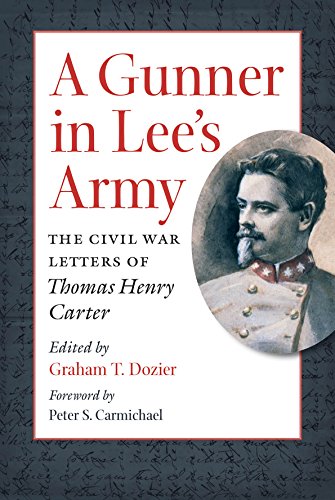

Colonel Thomas H. Carter’s letters, edited by Graham T. Dozier in A Gunner in Lee’s Army: The Civil War Letters of Thomas Henry Carter(University of North Carolina Press, 2014), cover the entire war from the perspective of one close to the army’s higher

echelons. A graduate of his home state’s Virginia Military Institute, Carter scrutinized events with a realist’s eye and the benefit of significant martial training. His observations about generals and the conduct of units enlivened many of the letters, as when he described the action at Turner’s Gap in South Mountain on September 14, 1862. “We had Hill’s (D.H.) Division & the remainder of Longstreet’s corps to contend with the whole Yankee Army,” he began. “Still I think with good management we could have held them in check…. Our men in many instances behaved very badly. Hills troops are mostly N[orth] Carolinians not our best troops by any means & his men have taken up the impression that he is rash & enter a battle with the idea that they are to be exposed to certain annihilation. Therefore they fought badly.” Thirteen months later, Carter offered his reckoning of Confederate prospects in the eastern theater. The army enjoyed “fine health and spirits” and with “Corps commanders like Jackson & Longstreet we might reasonably hope to give the enemy a decent thrashing. Ewell & Hill are poor concerns. Still I have great confidence in our troops, some of our leaders & in Providence & I believe we will drive them back, & possibly strike them a heavy blow.”Part of a family that stood at the apex of Virginia’s slaveholding class, Carter commented periodically about how the war, and especially the presence of United States military forces, affected white control of enslaved people. Late in the conflict, he supported enrolling African Americans in Confederate armies. “I think some fifty thousand should be mustered in immediately,” he argued, “& their freedom given the day they are mustered. Many would desert if they could with safety—so would the whites…. If we do not enlist them the Yankees will.” For Carter, a Confederate nationalist, the question boiled down to “the use of them or ultimate subjugation.”

William Thomas Poague was another Virginian who served in the Second Corps. A lawyer in Lexington, Virginia, when the war erupted, he enlisted in the Rockbridge Artillery and went on to attain the rank of lieutenant colonel. Nearly four decades after Appomattox, he wrote his memoirs, which Monroe F. Cockrell edited, together with some of Poague’s wartime letters, in Gunner with Stonewall: Reminiscences of William Thomas Poague(McCowat-Mercer, 1957). Bell I. Wiley contributed an introduction that described Poague’s account as “the recollections and judgment of an intelligent, articulate and fair-minded man, who was in the thick of most of the big eastern battles and one who knew and had the confidence of many key personalities, including Lee, Jackson, A.P. Hill, and W.N. Pendleton.”

Poague’s 16-gun battalion stood on the western edge of the Widow Tapp’s farm on May 6, 1864, when Winfield Scott Hancock’s II Corps smashed A.P. Hill’s lines. In one of the dramatic moments in the army’s history, the batteries held off the attackers just long enough for the leading elements of James Longstreet’s corps to restore the line. In the midst of the action, Lee rode forward with the Texas Brigade. “This was the first time General Lee ever advanced in a charge with his troops,” noted Poague in measured language, “and his action shows how critical the condition was at that juncture. I have often been asked about the appearance of General Lee at the time. He was perfectly composed, but his face expressed a kind of grim determination…. I suppose the scene was very similar to that of May 12 near the Bloody Angle.”

In a letter to his mother in November 1864, Poague wished that Abraham Lincoln fail in his bid for reelection but doubted that a Democratic victory would yield Confederate independence. “The Northern people haven’t got enough of the war yet,” he wrote: “There is still too much hatred towards the South and pride and Fanaticism among them to stop at this stage of the contest. They still have a sort of hope that they can conquer us. Very well: let them try.” Then Poague addressed the choice Confederates faced between continued resistance or surrender in the grinding last year of campaigning: “As for myself, although tired of this kind of life, yet I would not think of exchanging it for such a peace as Lincoln would offer. If I were to live three score and ten years, I would a thousand times choose to spend them as I have the past 3 or 4 of my life, than endure peaceful & quiet subjugation to yankee rule.”

Four Years in the Confederate Artillery: The Diary of Private Henry Robinson Berkeley, edited by William H. Runge (Virginia Historical Society, 1991), shifts the viewpoint to the ranks. Born into a prominent Virginia family, Berkeley remained a private

from his enlistment in May 1861 through the end of the war and saw action at the Seven Days, Fredericksburg, Gettysburg, Spotsylvania, Cold Harbor, and during the 1864 Valley Campaign. Captured at the Battle of Waynesboro on March 3, 1865, he finished his Confederate service as a prisoner at Fort Delaware. The entries in his diary, many of them brief but others quite lengthy, chronicle artillery action in battles, camp life, marches, the bond among men in a unit, interaction between soldiers and civilians, problems of equipment and supply, and other topics.

The diary features some compelling scenes. At Gettysburg on July 2, 1863, Berkeley walked the ground below Oak Hill where Alfred Iverson’s North Carolina brigade had been decimated the previous afternoon by Union infantry firing into their left flank. “This morning on getting up,” he recorded, “I saw a sight which was perfectly sickening and heart-rending in the extreme. It would have satiated the most blood-thirsty and cruel man on God’s earth. There were [with]in a few feet of us, by actual count, seventy-nine (79) North Carolinians laying dead in a straight line. I stood on their right and looked down their line. It was perfectly dressed. Three had fallen to the front, the rest had fallen backward; yet the feet of all these dead men were in a perfectly straight line. Great God! When will this horrid war stop?” Berkeley mentioned nearby bodies of other North Carolinians and some Federals, but his gaze focused on the seventy-nine. “I turned from this sight with a sickened heart and tried to eat my breakfast,” he continued, “but had to return it to my haversack untouched.”

On October 19, 1864, Berkeley described a lost opportunity for Confederate artillery at the Battle of Cedar Creek. Jubal Early’s infantry had routed two Union corps that morning and placed a third, Horatio Wright’s VI, in a vulnerable position. “[A]fter we had driven them to this point, we were halted,” wrote a disgusted Berkeley that evening, “just as Col. Tom Carter, our chief of artillery, had gotten 45 pieces of artillery ready to open on the Yankee Sixth Corps…. I don’t believe there is one particle of doubt that had we been permitted to open on those Yanks with our forty-five cannon, but that we certainly would have put them beyond the Potomac River.”

Some books convey the impression that artillery made a lot of noise without affecting the outcome of most battles. Wise countered that the guns exerted “a tremendous moral effect in support of their infantry, and adverse to the enemy” and precluded “heavy damage from the enemy by preventing him from essaying an assault against the position the guns occupy.” Testimony from Carter, Poague, Berkeley, and Porter Alexander supports Wise’s claim that the long arm compiled a well-earned record as a fighting component of the army.

GARY W. GALLAGHER IS THE JOHN L. NAU III PROFESSOR OF HISTORY EMERITUS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA. HIS PUBLICATIONS INCLUDE THE ENDURING CIVIL WAR: REFLECTIONS ON THE GREAT AMERICAN CRISIS(LSU PRESS, 2020).

This article appeared in the Fall 2021 issue (Vol. 11, No. 3) of The Civil War Monitor.

Read other installments in this series:

Part 1: Foundational Works

Part 3: European Observers

Part 4: Corps Commanders

Part 5: Division Commanders

Part 6: Managing the Cavalry

Part 7: Robert E. Lee