Library of Congress

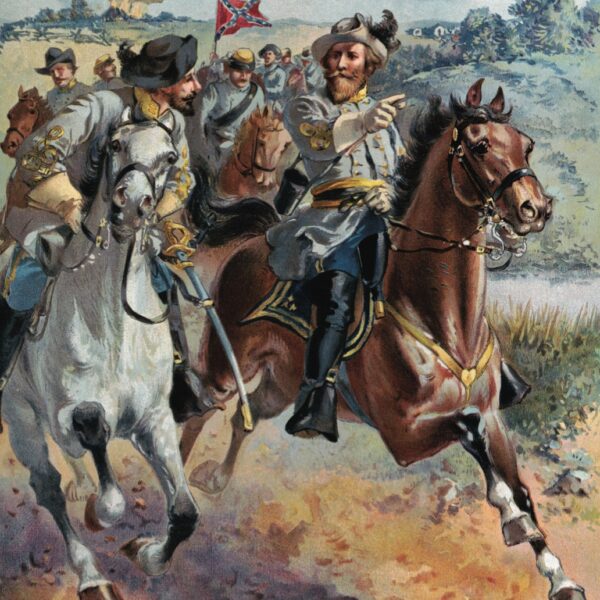

In this lithograph by Henry Alexander Ogden, James Ewell Brown “Jeb” Stuart leads his cavalrymen on a raid around George McClellan’s Union army in the summer of 1862.

This installment in the series focuses on the top leadership of the cavalry. The three titles include the correspondence of James Ewell Brown “Jeb” Stuart, by far the most important cavalryman in the Army of Northern Virginia, and Wade Hampton, his successor in 1864, together with staff officer Henry B. McClellan’s combination memoir and biography of Stuart. Other notable books with cavalry themes include William Willis Blackford’s literate and informative War Years with Jeb Stuart (1945); John Esten Cooke’s uneven but still valuable Wearing of the Gray (1867); and John N. Opie’s unassuming view from the ranks, A Rebel Cavalryman (1901).

The Letters of General J.E.B. Stuart, edited by Adele H. Mitchell (Stuart-Mosby Society, 1990), covers the life of a gifted soldier who hungered for attention, praise, and advancement. Stuart’s excellent relationship with Robert E. Lee began at West Point. “Last Saturday I had the pleasure of dining at Colonel Lee’s,” Cadet Stuart wrote of his superintendent in June 1853, “and found the Colonel in a fine humor. Mrs. Lee is still in Virginia, but we hope to see her again on the Point very soon. I have formed a high regard for the family.” Stuart’s reasons for resigning from the U.S. Army mirrored Lee’s. “For my part I have had no hesitancy from the first,” he advised a friend in January 1861, “that, right or wrong, alone or otherwise, I go with Virginia….” The correspondence underscores Stuart’s friendship with Lee’s sons Custis, a classmate at West Point, and Rooney, who served as his subordinate in the army’s cavalry.

Stuart’s self-absorption sometimes recalls that of George B. McClellan. After his second “Ride Around McClellan” in October 1862, Stuart wrote to his wife, Flora, “It is a march without a parallel—90 miles in 36 hours in one stretch besides the long march otherwise.” Terming it “my brilliant success,” he said she might be able to read some of the “marvelous accounts in the Northern papers.” The same letter closed with this: “You ought to have heard Emmitsburg and Leesburg hurrahing for your husband and showering bouquets and blessings. I never saw anything equal to it.” About a year later, in another letter to Flora, Stuart remarked, “My staff are so devoted to me. Isn’t it gratifying?”

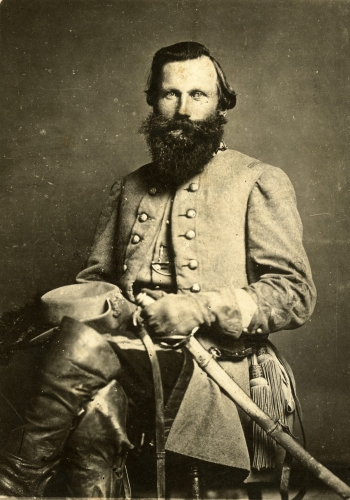

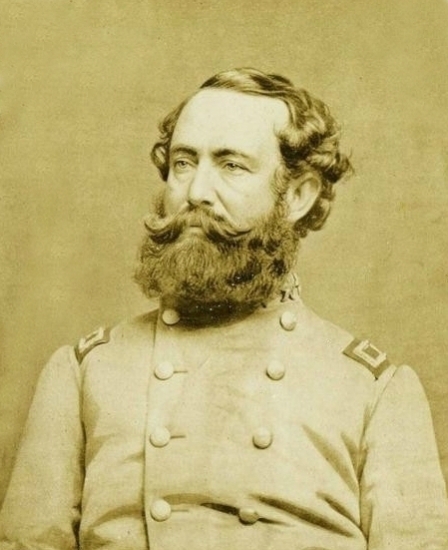

Jeb Stuart

Setbacks did not bring out the best in Stuart. A near-humiliation at Brandy Station on June 9, 1863, prompted a defensive reaction. His command had been taken by surprise, something noted in the Richmond Examiner and other newspapers, but Stuart insisted the “papers are in great error, as usual, about the whole transaction. It was no surprise. The enemy’s movement was known and he was defeated.” He treated the Gettysburg Campaign similarly—though his actions, which left Lee without vital intelligence for several days, came under heavy criticism at the time. Ten days after the battle, Stuart assured Flora, “My Cavalry has nobly sustained its reputation and done better and harder fighting than it ever has since the war.” Shortly thereafter he reiterated, “I have been blessed with great success on this campaign….”

Several letters highlight Stuart’s quest for promotion to lieutenant general. Creation of a two-division Cavalry Corps in early September 1863 seemed, in his mind, to clinch the case: “Wade Hampton and Fitz Lee are Major Generals Commanding Divisions in my Cavalry Corps, but I am not yet Lieutenant General.” In February 1864, his frustration boiled over. “I yield to no man in the Confederacy in quantity and quality of service…. I command two Divisions of Cavalry,” he sputtered, “While rank should be no patriot’s motive, it is nevertheless the acknowledged evidence of appreciation, and when withheld from one occupying a position corresponding to higher rank the inference is against the officer and prejudicial against him.”

Stuart developed an ardent loyalty to the Confederacy. In March 1863, he discussed what Flora should do in the event of his death. “I wish an assurance on your part,” he said, “… that you will make the land for which I gave my life your home, and keep my offspring on southern soil.” She should find “a nice little home of your choice. My darling one, don’t stay an instant where you are not contented; there is the whole Confederacy before you and I desire you to seek contentment….”

At 3 o’clock on the afternoon of May 11, 1864, Stuart sent a brief message to General Braxton Bragg in Richmond. “The enemy now has the Yellow Tavern and hold the Old Mountain Road for some distance above,” he wrote while a battle developed just north of the capital, “I have attacked once and feel confident of success.” Stuart was “glad to report enemy’s killed large in proportion.” Shortly after sending the message, he was mortally wounded by a dismounted Union cavalryman.

Wade Hampton

South Carolinian Wade Hampton proved an able successor to Stuart. Family Letters of the Three Wade Hamptons, 1782–1901, edited by Charles E. Cauthen (University of South Carolina Press, 1953), reveals a simmering tension between the two officers. A wealthy planter with no formal military training, Hampton resented what he saw as Stuart’s favoritism toward Virginians and members of the Lee family. Stationed near Culpeper in late November 1862, Hampton complained: “The country is exhausted and I do not see how we are to live. But Genl. Stuart never thinks of that; at least as far as my Brigade is concerned.” Stuart’s other brigades—including Rooney and Fitzhugh Lee’s—enjoyed better circumstances near Fredericksburg, “but of course mine has to take the hard work and starve in this poor country.” Two months later Hampton shared his sense of grievance with an aunt. “All my time and correspondence of late have been taken up in quarreling with Stuart, who keeps me here doing all the hard work, while the Va. Brigades are quietly doing nothing.”

Hampton commented acidly about Stuart’s quest for a lieutenant generalship. On May 19, 1863, he wrote from Culpeper, “Stuart will be here today I suppose, after his trip to Richmond where he went to have himself made Lt. Genl.” Hampton thought the effort would fail, “but there is no saying, how far newspaper puffs will go in this State.” Noting rumors that more cavalry from states south of Virginia soon would arrive, Hampton intended “to ask for it. This will bring up the question of my promotion and I will see what ground Stuart will take.” Relations between the two men never improved. In January 1864, Hampton again accused Stuart of creating a situation where “my command will be unfit for duty next spring.” Should that happen, “I shall ask to be transferred to some other army, or I will resign. I am thoroughly disgusted with the way things are managed here….”

In early July 1864, two months after Stuart’s death, Lee chose Hampton to succeed him. Hampton reported that the “Regts. from the other divisions greet me as kindly as those of my own.” He soon demonstrated great skill at discharging his increased responsibilities and in February 1865 was promoted to lieutenant general.

Major Henry B. McClellan, a first cousin of the celebrated Union general, served as assistant adjutant general to both Stuart and Hampton. The Life and Campaigns of Major-General J.E.B. Stuart, Commander of the Cavalry of the Army of Northern Virginia (Houghton, Mifflin, 1885; reprint titled I Rode with Jeb Stuart: The Life and Campaigns of Major General J.E.B. Stuart, Indiana University Press, 1958) presents McClellan’s admiring portrait of Stuart, supplemented with vignettes of his own activities and buttressed by many official documents. The book’s narrative of the cavalry’s principal operations remains an essential starting point for studying Lee’s mounted arm.

McClellan’s detailed handling of the Gettysburg Campaign absolves Stuart of misconduct while avoiding the hyperventilating rhetoric typical of the “Gettysburg controversy” of the 1870s. He discusses all of Stuart’s major decisions, explaining each as reasonable. Lee retained three brigades of cavalry when Stuart departed on June 24 to ride around the Army of the Potomac, asserts McClellan correctly, including that of William E. “Grumble” Jones—an irascible subordinate considered by Stuart “the best outpost officer” in the army. Acknowledging that it would have been better to leave either Fitz Lee or Hampton with the army, McClellan closes with a jab at the commanding general: “It was not the want of cavalry that General Lee bewailed, for he had enough of it had it been properly used. It was the absence of Stuart himself that he felt so keenly; for on him he had learned to rely to such an extent that it seemed as if his cavalry were concentrated in his person, and from him alone could information be expected.”

Parts of the book address the challenge of keeping men and horses prepared for action. The issue of horse supply stood out because the Confederacy determined in 1861 that it could not provide mounts for the cavalry units, passing that burden to individual recruits: “[T]he government should provide feed, shoes, and a smith to do the shoeing, and should pay the men a per diem of forty cents for the use of their horses.” Animals killed in action would be replaced by the government, but should “the horse be captured in battle, worn out, or disabled by any of the many other causes which were incident to the service, the loss fell upon the owner….” Anyone who could not procure another horse faced transfer to the infantry or artillery. This profoundly inefficient policy meant the loss of men who received 30- or 60-day leaves to find a new mount and left units chronically under strength. Maintaining this policy through the entire war, argues McClellan, “was a calamity against which no amount of zeal or patriotism could successfully contend.”

McClellan’s presence near Stuart’s side yielded dramatic anecdotes. The most intimate occurred in Richmond on May 12, 1864, when McClellan “repaired to the bedside of my dying chief.” In a conversation interrupted by the general’s “paroxysms of suffering,” he listened while Stuart “directed me to make the proper disposal of his official papers, and to send his personal effects to his wife.” A celebrated horseman, Stuart worried about his animals: “I wish you to take one of my horses and [Lieutenant Colonel Charles S.] Venable the other. Which is the heavier rider?” McClellan answered that Venable carried more weight. “‘Then,’ he said, ‘let Venable have the gray horse, and you take the bay.’” Aware that fighting continued north of Richmond, Stuart issued his last military order. “[L]istening to the distant cannonading for a few moments, he said: ‘Major, Fitz Lee may need you.’ I understood his meaning,” McClellan reported, “and pressed his hand in a last farewell.”

The next column, the penultimate in the series, will survey a foundational short list of published testimony from Robert E. Lee.

GARY W. GALLAGHER IS THE JOHN L. NAU III PROFESSOR OF HISTORY EMERITUS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA. HIS PUBLICATIONS INCLUDE THE ENDURING CIVIL WAR: REFLECTIONS ON THE GREAT AMERICAN CRISIS (LSU PRESS, 2020).

This article appeared in the Spring 2023 (Vol. 13, No. 1) of The Civil War Monitor.

Read other installments in this series:

Part 1: Foundational Works

Part 2: Artillerists

Part 3: European Observers

Part 4: Corps Commanders

Part 5: Division Commanders

Part 7: Robert E. Lee