Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia at Gettysburg

Four division commanders wrote letters that rival the best from anyone who served in the Army of Northern Virginia. The men wrote frequently and perceptively: Lafayette McLaws, a Georgian and for a time the army’s senior division chief; North Carolinians William Dorsey Pender and Stephen Dodson Ramseur, who died of wounds at Gettysburg and Cedar Creek, respectively; and Gabriel C. Wharton, a brigadier who fought in the Overland and 1864 Shenandoah Valley campaigns. Their letters discuss military topics, offer opinions about other officers and public events, and chart shifting morale and attitudes regarding Confederate prospects for independence. A fifth worthy letter writer is another North Carolinian, Bryan Grimes, whose Extracts of Letters of Major-General Bryan Grimes, to His Wife…, edited by Pulaski Cowper (1883; reprint, Broadfoot, 1986), is particularly useful for his descriptions of campaigning in the last year of the war.

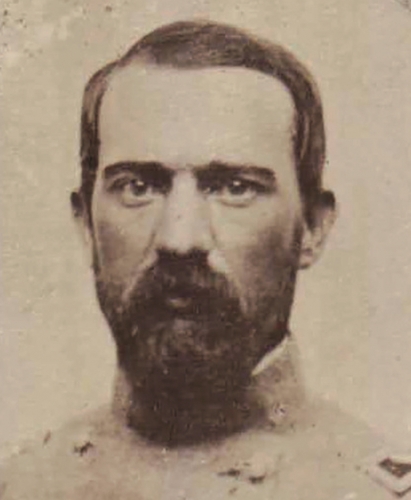

McLaws’ notoriously difficult handwriting long prevented scholars from making proper use of his personal correspondence. A Soldier’s General: The Civil War Letters of Major General Lafayette McLaws(University of North Carolina Press, 2002) represents a triumph for John C. Oeffinger, who managed the challenging transcription. Oeffinger’s efforts gave access to superb letters from an officer who participated in most of the army’s campaigns between the spring of 1862 and the summer of 1863 and later fought in Georgia, Tennessee, and the Carolinas.

Although McLaws is largely silent about several of his battles (the Seven Days, Antietam, Fredericksburg, and Chancellorsville, to name four), the letters should delight anyone interested in the Gettysburg Campaign, the 1862 Peninsula Campaign, and William Tecumseh Sherman’s operations in the Carolinas.

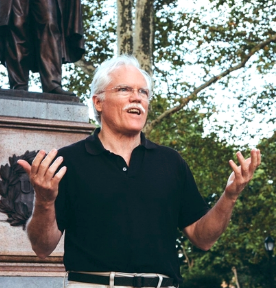

Lafayette McLaws

Beyond the battlefield, McLaws wrote about politics, the impact of the war on the Confederate home front, and numerous famous officers, including Robert E. Lee, James Longstreet, John Bankhead Magruder, and Joseph E. Johnston. A letter to his wife from December 1861 contains a superlative explanation about why the “loss of Richmond would be the most disastrous of events to our cause.” Manufacturing, communications, prestige as the capital, and other factors were such “that to lose that city would be to lose the State of Virginia at once, and almost oblige a disastorous retreat to the true land of Dixie, the land of cotton….”

A boyhood friend and West Point classmate of James Longstreet, McLaws made his name in the First Corps and benefited from his friend’s attention. The letters illuminate how a decades-long relationship deteriorated until, during the Knoxville Campaign of late 1863, Longstreet relieved McLaws of command. Demanding a court-martial, McLaws endured a guilty verdict before Adjutant General Samuel Cooper reversed the decision. He never returned to the First Corps. Perhaps the most quoted of the letters in A Soldier’s General, written to his wife on July 7, 1863, pulsed with anger about Longstreet’s actions on July 2 at Gettysburg. “Genl Longstreet is to blame for not reconnoitering the ground,” McLaws complained, “and for persisting in ordering the assault when his errors were discovered, and was exceedingly overbearing.” The next sentence delivered a blistering summary judgment on his commander: “I consider him a humbug—a man of small capacity, very obstinate, not at all chivalrous, exceedingly conceited, and totally selfish.”

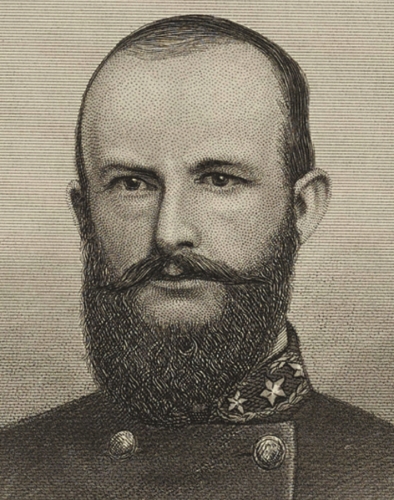

William W. Hassler edited The General To His Lady: The Civil War Letters of William Dorsey Pender to Fanny Pender (University of North Carolina Press, 1965; reissued in paperback as One of Lee’s Best Men: The Civil War Letters of General William Dorsey Pender, 1999), saying he undertook the project because “the animated correspondence” provides “many refreshing and poignant insights.” A member of the West Point class of 1854, Pender identified with the slaveholding South and resigned from the U.S. Army more than two months before North Carolina seceded. “I shall never regret resigning, whatever may turn up,” he wrote his wife, Fanny, on March 14, 1861: “I feel now as I felt then, that I could not serve in the U.S.A.”

William Dorsey Pender

Pender led a brigade in A.P. Hill’s “Light Division” from the Seven Days through Chancellorsville, surviving multiple wounds and earning a reputation as an excellent combat officer and a tough taskmaster with his own troops. “The men seem to think that I am fond of fighting,” he noted in December 1862. “They say I give them ‘hell’ out of the fight and the Yankees the same in it.” He developed a deep admiration for Robert E. Lee but never really warmed to Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson. During the Maryland Campaign of 1862, Pender wrote: “Gen. Lee has shown great Generalship and the greatest boldness…. Our men march and fight without provisions, living on green corn when nothing better can be had. But all this kills up our men. Jackson would kill up any army the way he marches and the bad management in the subsistence Dept.—Gen. Lee is my man.” But when Jackson lay near death after Chancellorsville, Pender remarked, “He will be a great loss to the country and it is devoutly to be hoped that he may be spared….”

In the army’s reorganization after Jackson died, Pender assumed command of the Light Division (less two brigades) as part of Hill’s new Third Corps. Soon on the road to Pennsylvania, he felt the burden of increased authority. “I have slept but little for two nights and I feel very sleepy,” he told Fanny on June 17. “Responsibility is a load that is anything but pleasant.” But he maintained his faith in Lee and the army. In his last letter, composed on June 28 in Pennsylvania, Pender wrote: “Everything seems to be going on finely. We might get to Phila. without a fight, I believe, if we should choose to go. Gen. Lee intimates to no one what he is up to, and we can only surmise.” On July 2 at Gettysburg, Pender was riding along his division’s line when a shell fragment struck his thigh. He died in Staunton, Virginia, two weeks later.

The Bravest of the Brave: The Correspondence of Stephen Dodson Ramseur, edited by George G. Kundahl (University of North Carolina Press, 2010), tracks Ramseur’s life from his teens to three days before his death at 27 on October 20, 1864. Ramseur shared more with Pender than their North Carolina origins and West Point educations. Three years younger and even more devoted to the South and its slavery-based social structure, Ramseur also resigned his U.S. commission well before his home state joined the Confederacy. As early as November 1856, he predicted war between the sections. “Our manners, feelings & education is as if we were different Nations,” he insisted. “Indeed, everything indicates plainly a separation. Look out for a stormy time in 1860. In the mean time the South ought to prepare for the worst. Let her establish armories, collect stores & provide for the most desperate of all calamities—civil war.” He became an ardent Confederate nationalist, suffered five wounds, and maintained a resolute determination to win independence.

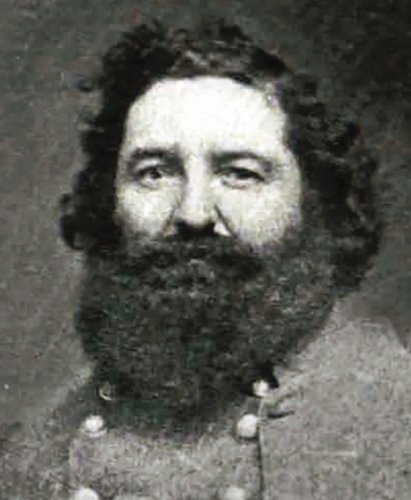

Stephen Dodson Ramseur

As a brigadier in Robert E. Rodes’ division of Jackson’s Second Corps, Ramseur distinguished himself at Chancellorsville and Spotsylvania. Ambitious and aggressive, he fit the model of leadership typical of successful officers in Lee’s army. “My Brigade covered itself with glory,” he commented after combat at Chancellorsville had cost his brigade nearly half its strength. “My loss has been very heavy,” he acknowledged. “I charged over two, or large parts of two, brigades from Va. who refused to march onward and meet the leaden storm of Yankee bullets. I [ran] over these timid friends….” His superior performance in the Mule Shoe at Spotsylvania on May 12, 1864, prompted a similar reaction. “On the 12th my Brigade did some of the best fighting of the war,” he wrote to his wife, Ellen (whom he called Nellie). “My loss has been heavy especially in men, the officers getting off quite well comparatively. I was slightly wounded thro’ the arm just below the elbow…. Some of our troops behaved shamefully.”

At age 27, Ramseur ascended to division leadership in late May 1864 and played a leading role in the 1864 Valley Campaign. His devout Presbyterianism and unflinching Confederate nationalism often comingled in his letters. “Let us pray for peace,” he implored Nellie from near Winchester on September 7. “That the minds & hearts of our Enemies may be turned from War & that our Heavenly Father will establish us in peace & independence. That we may be a Nation whose God is the Lord!” Defeats at Third Winchester and Fisher’s Hill later that month, both marked by Confederate collapses, left him “too much mortified to write” Nellie for several days. Yet he professed to “still feel confident of the final triumph of our cause…. We must steel ourselves for great trials. Let us learn to labor and to wait. Above all things let us never dispair of the Republic.” On October 17, Ramseur learned that Nellie had given birth to their only child. Two days later, as Federals massed to overwhelm his line at Cedar Creek, a musket round punctured his lungs, inflicting a mortal wound.

The Whartons’ War: The Civil War Correspondence of General Gabriel C. Wharton and Anne Radford Wharton, 1863–1867, edited by William C. Davis and Sue Heth Bell (University of North Carolina Press, 2022), usefully and unusually combines letters from Wharton and his wife Anne. Wharton’s military career lacked the high drama of Pender’s or Ramseur’s, but his letters contain rich material about military affairs and notable Rebel leaders. Anne Wharton’s correspondence contributes valuable testimony about morale, material conditions on the home front, and shifting relationships between enslaved people and slaveowners.

Gabriel C. Wharton

Serving in southwestern Virginia for much of the war, Wharton commented about officers such as John Echols, William E. Jones, and John Imboden. His frequently sharp assessments of these men contrasted with admiring passages about Robert E. Lee. Seeking to dampen Anne’s distress at news about Atlanta’s fall in September 1864, Wharton assured her that “Richmond will not fall, Genl. Lee is there. I have always thought the hopes of the Confederacy rested upon Lee’s Army. They cannot be whipped, we will not be whipped darling.” Atlanta’s loss, moreover, would recede quickly because “any decided success of our arms any where will bring about a rebellion at the North.”

Many letters deal with the 1864 Valley Campaign, during which Wharton led a small division. His remarks about Jubal Early warrant particular notice. On August 19, Wharton thought “General Early has done more than could have been expected.” On September 13, six days before the Battle of Third Winchester, he affirmed: “We would not like to give up ‘old Jubal,’ he is a crusty old rascal but a very skillful & able commander. He has the entire confidence of the troops in the Valley.” But defeats at Winchester and Fisher’s Hill changed Wharton’s mind, as a letter from October 11, about a week before Cedar Creek, revealed: “I want to get away from Early. He is too cold blooded, icy hearted. He is ambitious, has high intelligence, but no sympathy for any one & besides between us he drinks too much for a commander of an army.”

In addition to helping modern readers understand the Army of Northern Virginia’s campaigns and personalities, these four sets of letters highlight the stress of couples being separated by war. It seems almost intrusive to read some of the more intimate passages. McLaws’, Ramseur’s, and Pender’s letters, all still in print, and the just-published Wharton correspondence beckon all those interested in the history of Lee’s army.

GARY W. GALLAGHER IS THE JOHN L. NAU III PROFESSOR OF HISTORY EMERITUS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA. HIS PUBLICATIONS INCLUDE THE ENDURING CIVIL WAR: REFLECTIONS ON THE GREAT AMERICAN CRISIS (LSU PRESS, 2020).

This article appeared in the Fall 2022 issue (Vol. 12, No. 3) of The Civil War Monitor.

Read other installments in this series:

Part 1: Foundational Works

Part 2: Artillerists

Part 3: European Observers

Part 4: Corps Commanders

Part 6: Managing the Cavalry

Part 7: Robert E. Lee