J.E.B. Stuart leads the Army of Northern Virginia’s cavalry on its ride around the Army of the Potomac in 1862.

Between fall 2013 and summer 2016, I contributed seven short essays to The Civil War Monitor as “Voices From the Army of the Potomac.” Collectively, they examined more than two dozen titles about the largest and most famous Union army. This essay begins a comparable series on the Army of Northern Virginia that will also discuss primary accounts of various kinds and include a few secondary works. The first three titles are a memoir from the army’s premier artillerist, a set of letters from a member of Robert E. Lee’s staff, and the diary of a talented cartographer in the Second Corps.

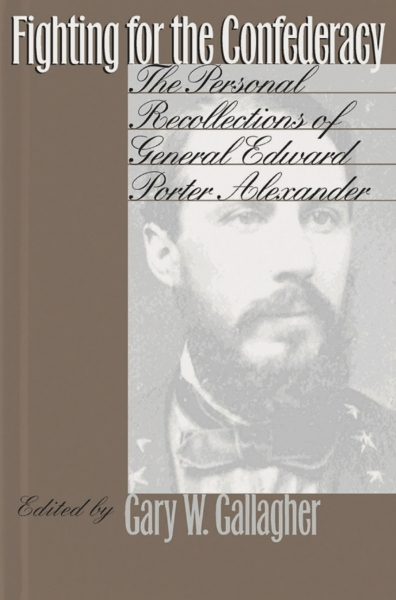

Any list of exceptional books on Lee’s army must begin with Fighting for the Confederacy: The Personal Recollections of General Edward Porter Alexander(University of North Carolina Press, 1989). Twenty-six years old at the war’s outset, Alexander served on the staffs of P.G.T. Beauregard, Joseph E. Johnston, and Lee before moving to the artillery, where he rose to command the battalions of the First Corps. The Georgia native participated in every major eastern campaign from First Bull Run through Appomattox and also fought at Chattanooga and Knoxville in 1863. In 1907, Alexander published Military Memoirs of a Confederate: A Critical Narrative, a book that, despite its title, offered an analytical history of the army leavened with personal observations. Rightly acknowledged a classic and widely cited by historians, the book left many readers wishing Alexander had told them more about his own activities. In fact, he had written such an account a decade earlier, a 1,200-page manuscript he drastically revised to produce Military Memoirs. During the late 1980s, I had the good fortune to edit and annotate the extensive manuscript, a process that proved to be the most enjoyable project of my career.

Fighting for the Confederacy contains a wealth of testimony from an eyewitness located near the center of operations. It combines analytical acuity, unsparing judgments about Confederate and Union officers, blunt descriptions of the brutal side of war, wry humor, and lyrical passages relating to famous battles and other events. Although an ardent Confederate, Alexander wrote with almost none of the Lost Cause special pleading evident in writings by most of his former comrades. Academic reviewers expressed astonishment that so valuable a memoir had remained unknown for so long. One termed it “a new landmark in Civil War historiography,” while another suggested it immediately would “join the list of essential readings for students of the war.”

Two passages suggest why Alexander’s book elicited such responses. At Chancellorsville, he described passions unleashed in

the heat of combat, betraying his own willingness to embrace a bloodthirsty approach to waging war. Confederate artillery moved forward from Hazel Grove to Fairview Cemetery on the morning of May 3, 1863, allowing Alexander to position his batteries to wreak havoc on retreating Federals. “[W]e deployed on the plateau,” he recalled, “& opened on the fugitives, infantry, artillery, wagons—everything—swarming about the Chancellorsville house, & down the broad road leading thence to the river. That is the part of artillery service that may be denominated ‘pie’—to fire into swarming fugitives, who can’t answer back…. One has usually had to pay for this pie before he gets it, so he has no compunctions of conscience or chivalry….”

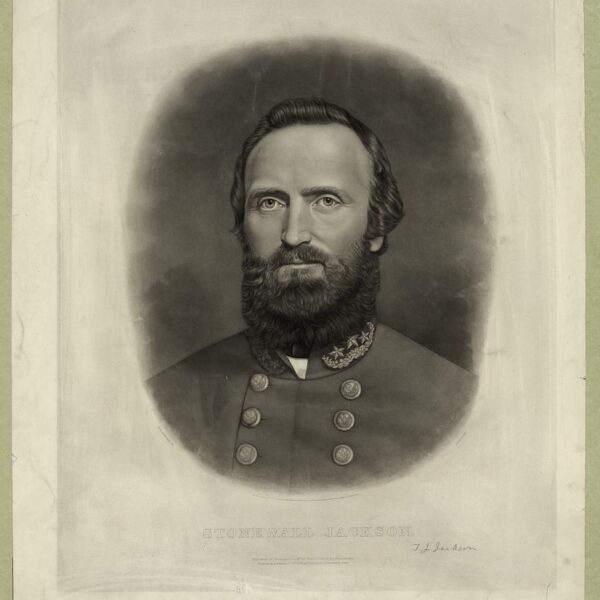

Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson came in for some of Alexander’s sharpest criticism. The Seven Days could have been a greater Confederate success, he insisted, had Jackson demonstrated any aggressiveness. Overall, Alexander deprecated the “incredible slackness, & delay & hanging back, which characterized Gen. Jackson’s performance of his part of the work.” The members of Lee’s staff, he added, “knew at the time that he [Lee] was deeply, bitterly disappointed, but he made no official report of it & glossed all over as much as possible in his own reports.”

No staff officer stood closer to Lee than Walter H. Taylor. The Norfolk, Virginia, native was just 23 when he was appointed to the general’s staff in 1861, and he remained at Lee’s side for the rest of the war. His two postwar books—Four Years with General Lee(1877) and General Lee: His Campaigns in Virginia(1908)—were frequently cited by ex-Confederates and later by innumerable historians, but it is Taylor’s wartime letters that contain unequaled testimony about Lee and the workings of his inner circle. Edited by R. Lockwood Tower, Lee’s Adjutant: The Wartime Letters of Colonel Walter Herron Taylor, 1862–1865(University of South Carolina Press, 1995) includes letters written between May 1862 and March 1865. This correspondence reveals that service on Lee’s staff involved an overwhelming burden of work and prompted frequent frustration as well as satisfaction from close association with a respected superior.

“The Tycoon,” as members of Lee’s official family sometimes called him, operated with a very small staff. In August 1863, Taylor complained to Bettie Saunders, his future wife, that while other generals had “ten, twenty, & thirty Ajt Generals, this army has only one and I assure you at times I can hardly stand up under the pressure of work.” He invited Bettie’s solicitude by grousing that he “never worked so hard to please any one, and with so little effect as with General Lee. He is so unappreciative.” A year later, the “General and I lost temper with each other,” recounted Taylor, “… he is so unreasonable and provoking at times. I might serve under him ten years to come and couldn’t love him at the end of that period.” But the next morning “he presented me with a peach, so I have been somewhat appeased. You know that is my favorite fruit. Ah! but he is a queer old genius. I suppose it is so with all great men.”

Taylor’s postwar books accorded a great deal of attention to superior Union numbers, something his wartime letters anticipated. “When I consider our numerical weakness, our limited resources and the great strength & equipments of the enemy,” he wrote after Chancellorsville, “I am astonished at the result.” Yet he did not believe the disparity in manpower doomed the Confederacy—a claim Lost Cause advocates repeated endlessly after the war. After a month’s carnage that included the battles of the Wilderness and Spotsylvania, he urged Bettie to “think nothing about our numerical weakness when compared with Grant’s army. Recently we have recd something less than several thousand reinforcements and have plenty of men to manage the enemy. Indeed we begin to feel almost comfortable.”

Jedediah Hotchkiss, a New Yorker who moved to Virginia in the 1840s, played a key role as Stonewall Jackson’s topographic engineer and continued in that position under Richard S. Ewell and Jubal A. Early. A gifted and prolific cartographer, he created maps that proved equally valuable to his commanders and to subsequent generations of historians (more than half of the Confederate maps in the Official Records were prepared by Hotchkiss). He also kept a dairy, edited by Archie P. McDonald and titled Make Me a Map of the Valley: The Civil War Journal of Stonewall Jackson’s Topographer(Southern Methodist University Press, 1973). His entries abound with revealing comments about Jackson and other Confederate officers, operations, and physical details about the terrain over which the armies fought between the spring of 1862 and the end of the war.

In the wake of Confederate defeat at Cedar Creek on October 19, 1864, Hotchkiss wrote a pointed assessment of Early and the

battle. “The general was very much prostrated when he learned the extent of our disaster,” read that night’s diary entry, “and started the wagons for the rear and sent for Rosser to come up and cover the retreat. He sent me to Edenburg to stop the stragglers. Thus was one of the most brilliant victories of the war turned into one of the most disgraceful defeats, and all owing to the delay in pressing the enemy after we got to Middletown….” Then Hotchkiss quoted Early’s summary of the debacle: “The Yankees got whipped and we got scared.”

After Joseph Hooker’s retreat from the Chancellorsville battlefield on May 5, 1863, Hotchkiss immediately began surveying the ground to prepare post-action maps. On May 12, he wrote, “We measured out the Brock Road thence up it to the Furnace Road and then up to Talley’s and measured several lines there,—then around the long line of defenses south of Chancellorsville.” The exercise left him with a central question about Hooker that many historians have pondered as well: “I had no idea the enemy was so well fortified and wonder why they left their works so soon.”

Foundational to any collection devoted to the Army of Northern Virginia, these three books illuminate countless scenes and personalities. The next installment will focus more narrowly on accounts relating to the army’s artillery.

GARY W. GALLAGHER IS THE JOHN L. NAU III PROFESSOR OF HISTORY EMERITUS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA. HIS PUBLICATIONS INCLUDE THE ENDURING CIVIL WAR: REFLECTIONS ON THE GREAT AMERICAN CRISIS(LSU PRESS, 2020).

This article appeared in the Summer 2021 issue (Vol. 11, No. 2) of The Civil War Monitor.

Read other installments in this series:

Part 2: Artillerists

Part 3: European Observers

Part 4: Corps Commanders

Part 5: Division Commanders

Part 6: Managing the Cavalry

Part 7: Robert E. Lee