Bryan Cheeseboro at Fort Stevens, where his interest in the Civil War was born.

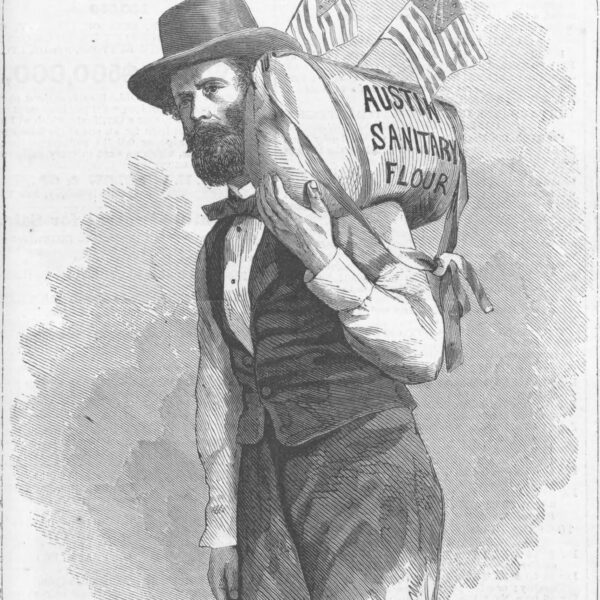

It was February 2004, and Bryan Cheeseboro was hurtling toward Olustee, Florida, in a van crammed with 5th United States Colored Troops reenactors. Cheeseboro had recently moved to Ohio, where the unit was based, and shot them a casual email, requesting information about upcoming events. Reenactors are renowned for their ability to detect serious interest, and they must have sensed it in Cheeseboro. Within a week, he was on that 15-hour road trip, fully kitted out for battle.

The van rumbled into the Olustee encampment late at night. “Everything had already been set up,” Cheeseboro recalled. “I step out of the van and in front of me I see the campfires. I see the tents. I hear the drums.” In reenacting parlance, what Cheeseboro experienced next was a “period moment.” Looking around, he lost sense of what century he was in. “It was just a minute, maybe two,” he said. “But I have never before or since had that feeling, that I was fully back in the past.”

For Cheeseboro, the veil between past and present has always been thin—maybe because he grew up on a Civil War battlefield. His childhood home sat just a block from Fort Stevens, one of 68 forts that formed a defensive ring around Washington, D.C., during the conflict.

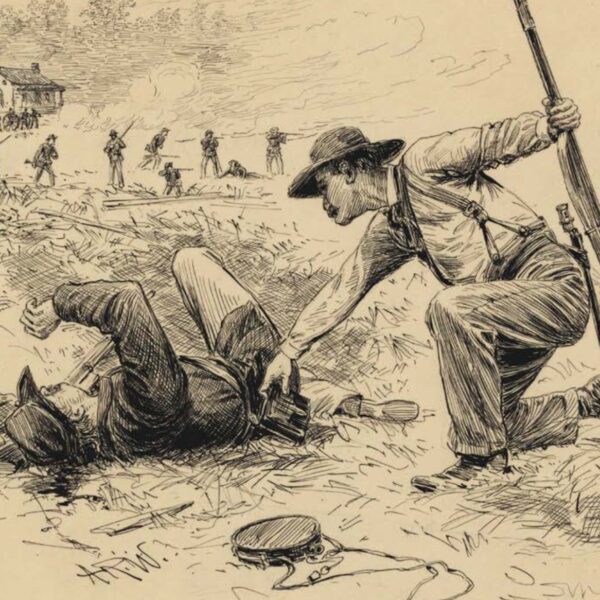

It is where, in July 1864, Union forces repelled Jubal Early’s attack on the capital; Abraham Lincoln stood on Fort Stevens’ parapet to observe the fighting, coming under fire from Confederate sharpshooters. For Cheeseboro, the fort was the backdrop of his early life, a focal point for his imagination. “If you look at the battle lines on a map, they went right through our house,” he said.

Cheeseboro was born in 1965, the closing year of the Civil War centennial. His family wasn’t drawn to history, but he was. He spent countless hours absorbed in books and TV programs on the subject. “I don’t know if it’s that history found me, or I found it,” Cheeseboro reasoned. He also developed a keen interest in black history—reading about black Civil War soldiers, studying pictures of the Tuskegee Airmen of World War II, and seeking any sources he could find. In seventh grade, he got lucky in his school’s choice of American history textbooks: Henry Graff’s The Free and the Brave, published in 1967.

The book included more black and Indigenous history than any book he had encountered and quickly earned his reverence. (The school let him keep the book. He read it so often that he wore it out, replacing it with a copy he found in a used bookstore.)

As Cheeseboro grew up, history stuck with him. In the ’80s, he headed west to Iowa State University to earn a degree in history. For as much as he learned in school, he learned more on his own. His shelves swelled with books on the Revolution, the War of 1812, social history, world wars, and U.S. presidents. But most of them focused on the Civil War. “I just see it as the epicenter of American history, where everything can be divided into what came before it and what’s come after,” he said. Cheeseboro didn’t read these books so much as reach into them, trying to relate to people’s personal experiences in the era. After reading an account of a slave escape in a particular part of Maryland, he drove around that area, wondering, “Did that person cross this path? Did they go through here? What was that like?” he said. “I think about these things.”

It seemed a long shot that Cheeseboro would find a job that matched his passion. He taught school for a while, and tried other vocations. In 2003, he got married, relocated to Ohio, and soon after got his wild launch into reenacting. In 2007, he was four years into a job at a library, working the reference desk, when his phone rang. It was the National Archives in Washington. Cheeseboro had applied for a job more than a year earlier and given up on hearing back. That phone call, it turned out, was his job interview. His long-shot career had arrived.

At the archives, Cheeseboro started working directly with 19th-century records, transcribing, digitizing, and examining Civil War pension files and other period documents rich in stories and information. For years now, anyone who has contacted the archives searching for a Civil War ancestor or researching a particular unit has probably crossed paths with Cheeseboro.

He loves the surprise that opening a long-closed file can bring. It was Cheeseboro who recently unearthed a rare tintype of Will Calhoun, a soldier in the 67th United States Colored Troops, in response to a research query. Even an everyday letter found tucked inside a pension file gets his mind racing. “I don’t think any of these soldiers expected any of this would be saved, let alone end up in a place called the National Archives,” he said. “That kind of stuff blows me away.”

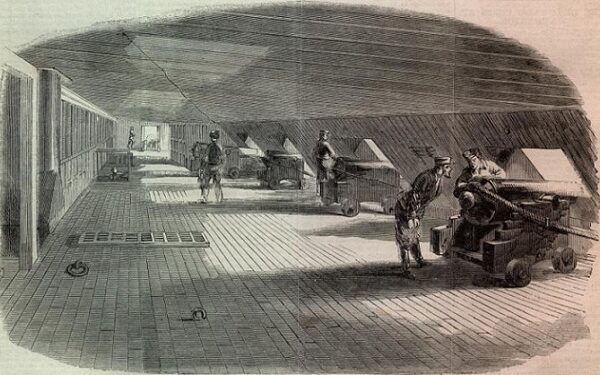

Fort Stevens in 1864

Back now in Washington, Cheeseboro still felt that pull toward Fort Stevens. He started attending events at the fort, and soon landed on the board of the Alliance to Preserve the Civil War Defenses of Washington. “You grow up just a block away from a place that, later, you’re going to devote a piece of your life to helping make sure gets preserved,” Cheeseboro said. “It all kind of came full circle.” He started speaking at Civil War roundtables, opened new research into the black presence at Fort Stevens and other D.C. defenses, and launched the Civil War Era Historian page on Facebook, which has 2,300 members.

After a brief hiatus, Cheeseboro also returned to reenacting, this time with a D.C.-based unit of the 54th Massachusetts.

The release of Glory, in the late 1980s, sparked an overnight explosion in black reenacting, with the 54th, the regiment depicted in the film, at the center. Cheeseboro prized being in the company of other black men who shared his passion and had their own version of war stories to tell. But the regiment’s stalwarts have grown older, and their ranks aren’t being replenished. “The 54th doesn’t do many battles anymore,” Cheeseboro said, wistfully. “Because I came in later, I feel like I missed out on a lot of stuff.”

But reenacting let Cheeseboro put his hands on history in ways he couldn’t otherwise; he didn’t want to give it up. So he charted a new course for himself, becoming a sort of free-agent reenactor. He sought out different groups to reenact with and events to attend—regardless of whether there was a black unit or any black soldiers recorded at a particular battle. He’s made great friends that way. Showing up on the field—and making a point of recruiting diverse participation in Fort Stevens’ annual reenactment—is his way of demonstrating what a more inclusive version of reenacting can look like. “It’s an overwhelmingly white hobby, but you don’t have to be white to want to be a part of it,” Cheeseboro said. “Everybody should have a chance to engage with history.”

Not everyone shares his views.

Cheeseboro has rebuffed dozens of efforts to recruit him as a “black Confederate,” the dangerous myth that free and enslaved blacks served willingly in the Confederate army. Other reenactors, Union and Confederate, flat-out shun him. “I’ve encountered some people who had a problem with it, or weren’t expecting it,” Cheeseboro said. He remains philosophical. “I’m all about accurate history. But the truth is, most of the people who reenact are too old, too tall, too fat, too something, to have been Civil War soldiers. I’ve never seen anybody bleed to death on the battlefield, or run from the field screaming for their life.” He added: “There’s only so much we can do that’s really authentic—maybe none of it.”

Cheeseboro being on the field does make a difference. A few years ago, a friend who portrays a Union officer invited Cheeseboro to join his all-white unit at a reenactment in North Carolina. “I was drilling with them, but I could tell by the look on some faces that they weren’t accepting me,” he recalled. One of the soldiers singled him out, leveling a racist comment. Soon afterward, they all marched onto the battlefield. Among the spectators that day was a young black boy. “He saw me and leaped up, and just waved and waved.” Cheeseboro waved back, and held the boy’s gaze. “I made sure that I kept looking at him as long as I could,” he said. “I wanted him to remember me.”

Jenny Johnston is a freelance writer and editor based in San Francisco.

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2021 (Vol. 11, No. 1) issue of The Civil War Monitor.