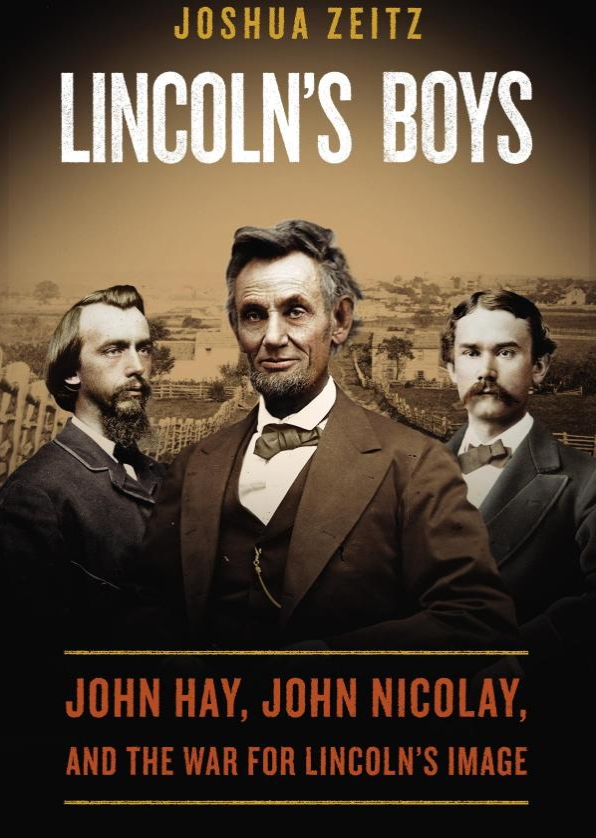

Lincoln’s Boys: John Hay, John Nicolay, and the War for Lincoln’s Image by Joshua Zeitz. Viking Press, 2014. Cloth, ISBN: 978-0670025664. $29.95.

Astounding as it may seem to modern Americans, Abraham Lincoln administered a sprawling civil war for four years with an administrative staff that consisted largely of two assistants: John Hay and John Nicolay. “As Abraham Lincoln’s private secretaries, they became, both literally and figuratively, closer to the president than anyone outside his immediate family,” Zeitz observes (2). In Lincoln’s Boys, author Joshua Zeitz relates the life stories of Hay and Nicolay, their relationship with President Lincoln, and their efforts after the war to safeguard his legacy.

Astounding as it may seem to modern Americans, Abraham Lincoln administered a sprawling civil war for four years with an administrative staff that consisted largely of two assistants: John Hay and John Nicolay. “As Abraham Lincoln’s private secretaries, they became, both literally and figuratively, closer to the president than anyone outside his immediate family,” Zeitz observes (2). In Lincoln’s Boys, author Joshua Zeitz relates the life stories of Hay and Nicolay, their relationship with President Lincoln, and their efforts after the war to safeguard his legacy.

Zeitz is blessed in this endeavor by the fact that Nicolay and Hay were each themselves interesting young men. They both made Lincoln’s acquaintance in the rough-and-tumble political circles of antebellum Illinois: Nicolay as a newspaper editor and minor operative for the state’s Republican Party, and Hay as a law student in Springfield. President-elect Lincoln noticed Nicolay organizational abilities, and asked him to serve as his private secretary; Nicolay, in turn, requested Hay as an assistant.

They were perfectly positioned in the Lincoln White House to observe (and often comment upon) the momentous events of their time. The secession crisis, the outbreak of war, Lincoln’s frustrating search for a competent commanding general, his progress toward emancipation, the war’s sometimes Byzantine political cross-currents—Nicolay and Hay saw it all, from the inside. They kept the president’s appointments, answered much of his correspondence (in all likelihood, Lincoln’s famous “Bixby Letter” was authored by John Hay), and witnessed firsthand Lincoln’s private tragedies, such as the death of his young son Willie in 1862. “They learned how to anticipate his thought process,” Zeitz notes, “and he increasingly granted them leeway in managing access and work flow” (91).

They were different: Nicolay, the dour and often abrasive gatekeeper to presidential access, with a “stiff and businesslike demeanor” that could rub people the wrong way; and Hay, the bright and gregarious ladies’ man, “given to daydreaming and flights of fancy,” who once wanted to be a romantic poet (12, 60). Nicolay was the “grim enforcer,” Hay the “smiling emissary to cabinet members and congressmen” (78). Yet there were also similarities. Lincoln’s boys both performed their tasks surprisingly well, given their lack of experience and youth. They were both unswervingly loyal to the president, and they both despised (and in turn were heartily despised by) Mary Lincoln, whom they privately nicknamed “The Hellcat.” And they both possessed a steely-eyed determination after the war to “canonize their boss as a great leader among men, not a saint or a martyr” (60).

Their most important contribution in that regard was their co-authorship (with Robert Lincoln’s active cooperation) of a sprawling, ten-volume biography of Lincoln, first serialized in Century and then published between 1890-1894. Their biography is not only an important primary source on Lincoln’s presidency; it likewise created an enduring image of Lincoln as a master politician and wartime leader, whose superior sagacity and authority” was a model for all Americans (280). They also took aim at the growing “Lost Cause” mythology in the postwar South, “hacking down the idols of Confederate mythology” like Robert E. Lee and “Stonewall” Jackson, and instead portraying Northern leaders—Grant, Sherman, and, of course, Lincoln—as the true heroes of the Civil War (274). Zeitz argues that they were remarkably successful in “creating not just a particular image of Lincoln, but also “pioneer[ing] the ‘Northern’ interpretation of the Civil War” (4).

Both men later enjoyed successful public careers. Nicolay became a Chicago newspaper editor, United States consul to France, and then Marshal of the U.S. Supreme Court. Hay’s postwar career was even more stellar. He served in a variety of diplomatic posts in Europe, as assistant Secretary of State in the administration of Rutherford B. Hayes, and then as Secretary of State for William McKinley. But it was their close proximity to arguably the greatest president in American history—and their own enduring friendship with each other—that came to define their own lives and legacies. “The greater Lincoln grew in death, the greater they grew for having known him so well, and so intimately, in life,” Zeitz writes (3).

Lincoln’s Boys is a fine book, and perhaps surprisingly so, for such a dual biography contains inherent pitfalls. One subject or the other may come to dominate at the expense of balance. Or, in an attempt to maintain that balance, the author may create a ping-pong quality, bouncing the reader’s attention tediously back and forth with little sense of an over-arching theme or story. Happily, Zeitz avoids these problems. He is an excellent writer with a fine eye for detail and telling anecdotes. He knows how to carry forward such a complex story, with so many moving parts, in a tight and riveting narrative. Above all, Zeitz’s book is simply a very good read.

Brian Dirck is Professor of History at Anderson University. He is the author of many books on the life of Abraham Lincoln, including Lincoln and Davis: Imagining America, 1809-1865 (2001).