Major Charles P. Mattocks and his two comrades, Captain Julius P. Litchfield and Lieutenant Charles O. Hunt, were on the run. The three Maine Yankees, each the member of a different regiment, had been held captive since the Battle of the Wilderness in early May, 1864. Six months later, on Thursday afternoon, November 3, the trio slipped away from a Confederate prison camp outside Columbia, South Carolina. They hoped to reach Union lines in East Tennessee. But three hundred miles of hostile terrain and formidable mountains lay ahead of them.

The first challenge they faced was the Saluda River, between 150 and 200 yards wide. A raw cold rain was falling. To minimize any chance of detection, they concealed themselves until it was almost dark. The three then plunged into the frigid water with their hands on a plank that carried their only outergarments—two old blankets. Hunt (who was not a swimmer) and Litchfield nearly despaired and told Mattocks “we never can get across.” But the resourceful young Major, who had just turned twenty-four, challenged them to preserve. “Yes, we can,” he insisted, “look ahead and kick.” Dangerously chilled and exposed, they finally reached the far shore.

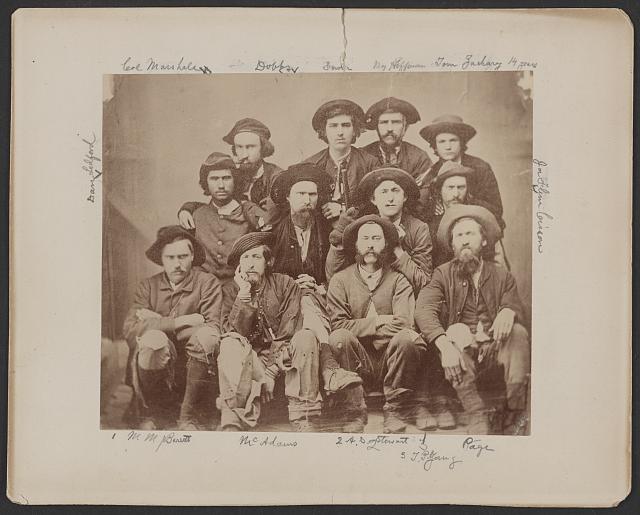

Mattocks had an instinct for command. At Bowdoin College, Professor Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain challenged him to bear down and live up to his potential. In the summer of 1862 when Mattocks graduated, both he and Chamberlain enlisted in the army. Mattocks’ no-nonsense attitude impressed his superiors. Standing five feet nine inches tall with blue eyes and light hair, he was mature beyond his years. He also possessed an intangible attribute: luck. His regiment lost over 100 killed and wounded in the Wheatfield at Gettysburg on July 2, 1863, including the two men standing next to him. At four in the morning on July 3, he wrote to his mother about the “terrible fight”—“and yet I am safe.” In January 1864, when the colonel of the 17th was promoted to head the brigade, Mattocks became the top officer in his regiment.

The runaway venture, however, was quite unlike anything Mattocks ever had attempted. He and his companions dared not rest after surviving the river crossing. Only in darkness could they proceed with any safety. Before dawn they trekked fifteen miles, but soaked boots blistered their feet. And for their first two days they had next to no food—“a small piece of wet bread.” Things changed for the better on Saturday evening, when a kindly slave “took us to his cabin, where we feasted on chicken, corn bread & potatoes” and “toasted our feet by his fire.”

This encounter vividly drove home the first rule for escaping Union POWs—the only face you could trust in the lowlands of the Confederate South was a black one. Mattocks and his friends, absentmindedly dismissive of “darkies” before their escape ordeal, decided that slaves were “as true as steel.” Their “black benefactors” kept supplying them en route, even at the risk of “100 lashes, well laid on” for aiding a Union runaway.

But even with surreptitious support, life on the road was bleak. Only intermittently did they eat adequately; often they subsisted on uncooked corn or potatoes. Relentless night marching and constant fear of recapture left Mattocks “so much exhausted” that he twice fainted one night and had to stop. He “never would have believed that a person could do so much with so little food.” Their feet and toes were made raw by “swimming rivers and marching in mud.” To ease the pain, they cut holes in their boots. On November 8, as they hid concealed in the woods, they realized the presidential election was taking place far away in the United States.

Many nights of strenuous marches brought Mattocks and his two companions to Jones Gap, on the border between North and South Carolina. By moonlight they admired “the deep ravines, the sparkling cascades and waterfalls, [and] the mammoth southern pines growing among huge rocks” as they clambered up and down the “perfect zigzag” of a road that carried them across the Blue Ridge escarpment. They dared to hope that they had passed “the most dangerous portion of our journey.”

Fewer blacks lived in the North Carolina uplands, but one was able to direct them to the home of a white loyalist, A. J. Loftis—“the first white man we have spoken with for more than two weeks.” He secreted them in his “old corn house,” shared with them some his precious apple-jack (“There, boys, suck away at that. It will do you good”), and brought them “a fine breakfast of beef, pork, apple sauce, [and] vegetables.” Mattocks judged it “the best meal I ever ate.” He apologized for his “phenomenal appetite”—“Fact is, Mrs. Loftis, we’ve been living on raw corn for three days.”

Before long, the three Maine soldiers enlisted a “special guide,” Gilbert Sautel, to lead them and a number of other escaped prisoners to safety in Tennessee. Mattocks noted that the “thoroughly Union” inhabitants of the region were well armed and were shielding “many deserters and soldiers of the Rebel army.” The Union underground moved them from house to house. When loyal Carolinians realized that “genuine Yankees” needed assistance, “their joy knows no bounds, and they do all that their limited means will allow.” Old men and women, girls and boys—all “look upon us as their warm friends and perhaps their future deliverers from Rebel rule.”

The escapees and their guide did not dare to follow the valley of the French Broad River, the obvious travel route to Tennessee. Too many Confederate pickets patrolled the lowland roads. Instead they attempted to cross through the mountains. By so doing, they could travel by daylight, but the rugged terrain and the cold weather pushed them to the physical limit. “The marching or rather, the climbing up and down these mountains is the hardest labor I ever undertook,” Mattocks realized. “Campaigning in the army is often hard, but until this trip I never knew what it was to actually suffer from hunger, cold, thirst, [and] sore feet.” Army life was “boy’s play when compared with this.”

Unfortunately for the Yankee runaways, their guide was befuddled by early winter snows that concealed familiar landmarks. They found themselves “horribly lost” in a “desolate region” of “almost impenetrable” mountain laurel, with their clothes shredded, their food supplies gone, and no homes in sight. They did their best to “travel due N. W. by our compass.” Without axes or hatchets, they could not build “an all-night fire” and so they awoke “shivering over a few embers.” Mattocks once lost his footing on icy rocks and tumbled into a “rapid mountain stream” that gave him “a sousing even to my arm-pits.” Hunt’s feet, after “jumping from rock to rock with wet boots, developed a large blood blister the full size of one of my heels,” so that he could barely continue. But the guide boosted their spirits by promising that they would reach Union settlements in Tennessee “by 2 o’clock tomorrow afternoon.”

A safe destination was indeed tantalizingly close, but fate intervened. On Monday, November 28, three armed Confederate scouts, or bounty hunters, emerged from the woods and “demanded our surrender.” The three Mainers and the others who had joined them had no choice but to comply. Once again prisoners, they were forced to walk to Asheville and then to Morgantown, well over one hundred miles. They were then transported by train to a prison camp in Danville, Virginia. “By my table of distances,” Mattocks sourly observed, “I find we have marched 413 miles and ridden by cars 140 miles.—all for nothing!” Their situation could have been worse. The captives pretended that their civilian guide was a Union soldier, but the Confederate bounty hunters determined otherwise. They tortured and shot the unfortunate Sautel, and left his body lying on the road.

Mattocks remained a captive until late February, 1865, when he was released. A month later he rejoined the 17th Maine, stationed outside Petersburg, Virginia. During the last week of the war, after Confederates abandoned their Petersburg defenses, the 17th was “quite hotly engaged.” At Sayler’s Creek on April 6, while under heavy fire, Major Mattocks rallied his men. “Give me the flag,” he shouted. “All who will, follow me!” Over one hundred startled Confederates surrendered as the Yankees swarmed toward them, and Mattocks was subsequently awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. Writing to his mother from Appomattox Court House on April 10, Mattox rejoiced that he had returned to action when he did—“I would not have missed these ten days for all the world.”

After the war Charles Mattocks earned a law degree at Harvard, moved to Portland, raised a family, and launched a career in law and politics. When he died in 1910, his aging former teacher and fellow warrior, Joshua Chamberlain, pronounced his valedictory.

Daniel W. Crofts, Professor Emeritus of History at The College of New Jersey, is completing a new book: Lincoln’s Other Thirteenth Amendment: Rewriting the Constitution to Conciliate the Slave South.

Sources: Philip N. Racine’s splendidly edited volume, “Unspoiled Heart”: The Journal of Charles Mattocks of the 17th Maine (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1994), draws on the Charles Porter Mattocks Papers 1840-1910, Bowdoin College Library. The collection includes Mattocks’ Civil War diaries and letters. See also John C. Inscoe, “‘Moving Through Deserter Country’: Fugitive Accounts of the Inner Civil War in Southern Appalachia,” in Kenneth W. Noe and Shannon H. Wilson, eds., The Civil War in Appalachia: Collected Essays (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1997), 158-86; Philip S. Paludan, Victims: A True Story of the Civil War (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1981); John C. Inscoe and Gordon B. McKinney, The Heart of Confederate Appalachia: Western North Carolina in the Civil War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000); Martin Crawford, Ashe County’s Civil War: Community and Society in the Appalachian South (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2001); John C. Inscoe and Robert C. Kenzer, eds., Enemies of the Country: New Perspectives on Unionists in the Civil War South (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2001).

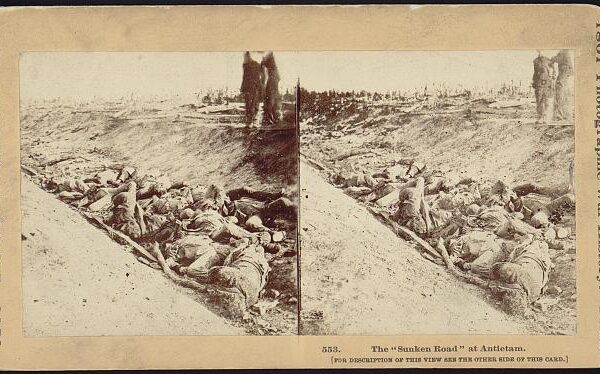

Illustration Courtesy The Library of Congress (loc.gov)