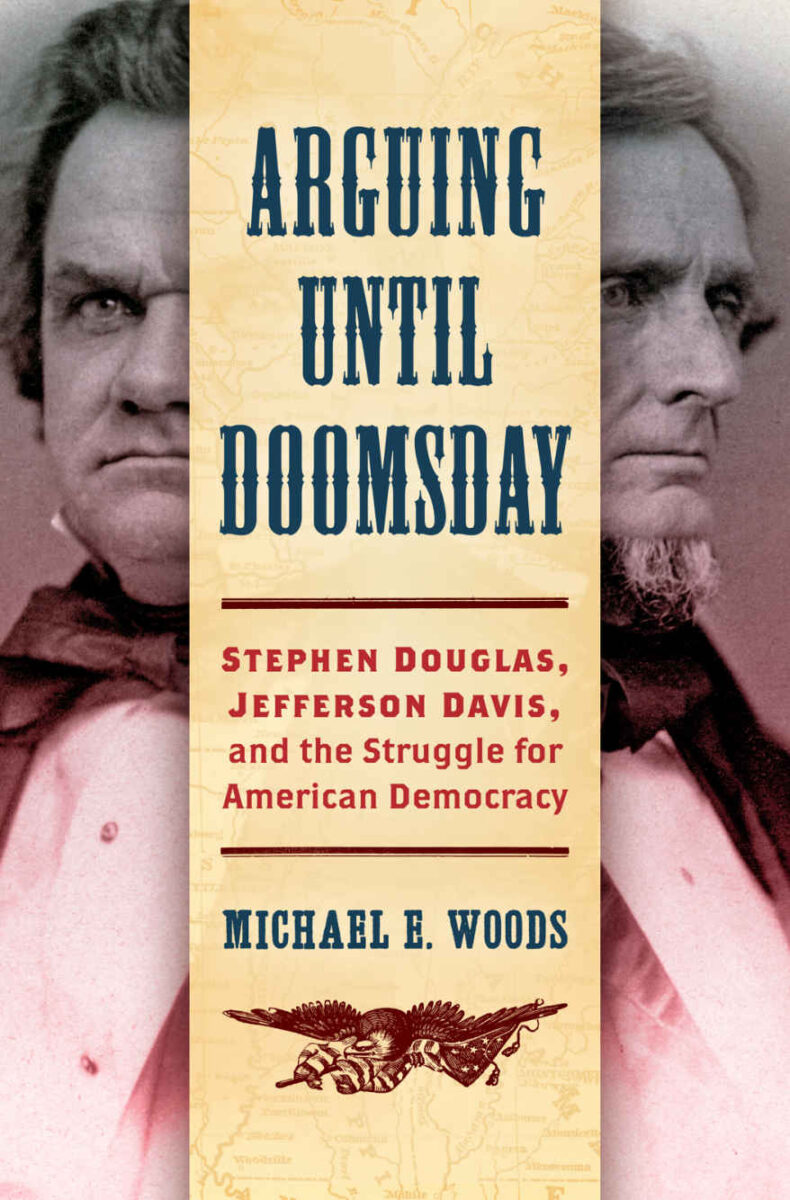

Listening to a debate between Stephen Douglas and Jefferson Davis in February 1859, Georgia senator Alfred Iverson told his colleagues, “If we permit these gentlemen to go on brandying arguments with each other we shall never come to the end of the question….They can go on arguing against each other from this until doomsday” (1). In his new book, historian Michael E. Woods uses the “parallel lives and intertwined careers” of Douglas and Davis “to trace the long history of the Democratic Party’s collapse” on the eve of the Civil War (4).

Traditionally, histories have compared Douglas and Davis to their mutual antagonist Abraham Lincoln. Woods argues that a more instructive comparison is the one to be made between Douglas and Davis—both men within the same political party who represented differing sectional interests. Douglas, representative of Northern Democrats, and Davis, a hardline southerner, argued until their party collapsed under the demands of sectionalism (3). More than just a study of the antebellum Democratic Party, Woods also “seeks to reinterpret, though not vindicate, Stephen Douglas” (5).

The Democratic Party was an uneasy political alliance that was held together by “racism, nationalism, and party affinity,” and the alliance would “collapse if northerners concluded that slavery endangered democratic liberty, or if southerners decided that majority rule menaced their peculiar property” (47). The sectional rivalry embodied in Davis and Douglas, Woods argues, reveals “the fragility of racism and negative partisanship as foundations of party unity” (144). Debates over popular sovereignty and slavery’s westward expansion “splintered” the “deplorably broad consensus that the United States must remain a white man’s country” (152).

Though both protagonists claimed the mantle of the Democratic Party, each man harbored different ambitions. Davis sought to use the Democratic Party to nationalize slavery, while Douglas sought to use it as a vehicle for realizing the interests of Westerners. Davis the “southern sentinel would safeguard slaveholders’ current and prospective domain, while the western gadfly would empower pioneers to harvest the fruits of empire” (84). That Douglas was the western gadfly—someone who sought to bring the West more powerfully into the American political fold—is Woods’s greatest contribution to his reinterpretation of Douglas.

A brief epilogue explores the theme of solidarity in Davis’s political rhetoric as Confederate President. Davis had learned that “slavery was insecure when free people were divided, but in the Confederacy, [slavery] was a source of unity and therefore would be safe” (224). “Much like the antebellum Democratic Party,” Woods explains, “Davis’s Confederacy promised to safeguard property rights while ensuring equality among white men” (226). However, just as racism proved a poor “glue” for the antebellum Democratic Party, slavery could not hold the Confederacy together as internal divisions wrenched the new nation apart from the beginning.

Woods has written one of the most engaging and accessible histories of the pre-Civil War Democratic Party to date. His narrative approach and the biographical bent helps to clarify how Americans—and Democrats in particular—wrestled “with thorny questions about property rights, democracy, race, slavery, and freedom” (7-8). Framing the Douglas-Davis debate around the West advances the field of American political history and affords nuance to a period that is always in danger of becoming oversimplified. Though hardly inspiring, this story of the Democratic Party “underscores…that no political coalition is ever monolithic” (227). With the 2020 presidential election fast approaching, Woods’s history is timely in its warnings and lessons.

Caleb W. Southern is a graduate student in the Department of History at Sam Houston State University.