Americans tend to imagine their Civil War through a montage of images. For most, this visual archive is littered by the sepia-toned portraits and Ken-Burns-styled landscapes. Color photos of tranquil battlefield parks also play their part, as do imposing monuments to soldiers and generals. Abraham Lincoln occupies a place all his own, being at once America’s indispensable martyr-savior and its pre-eminent historical icon.

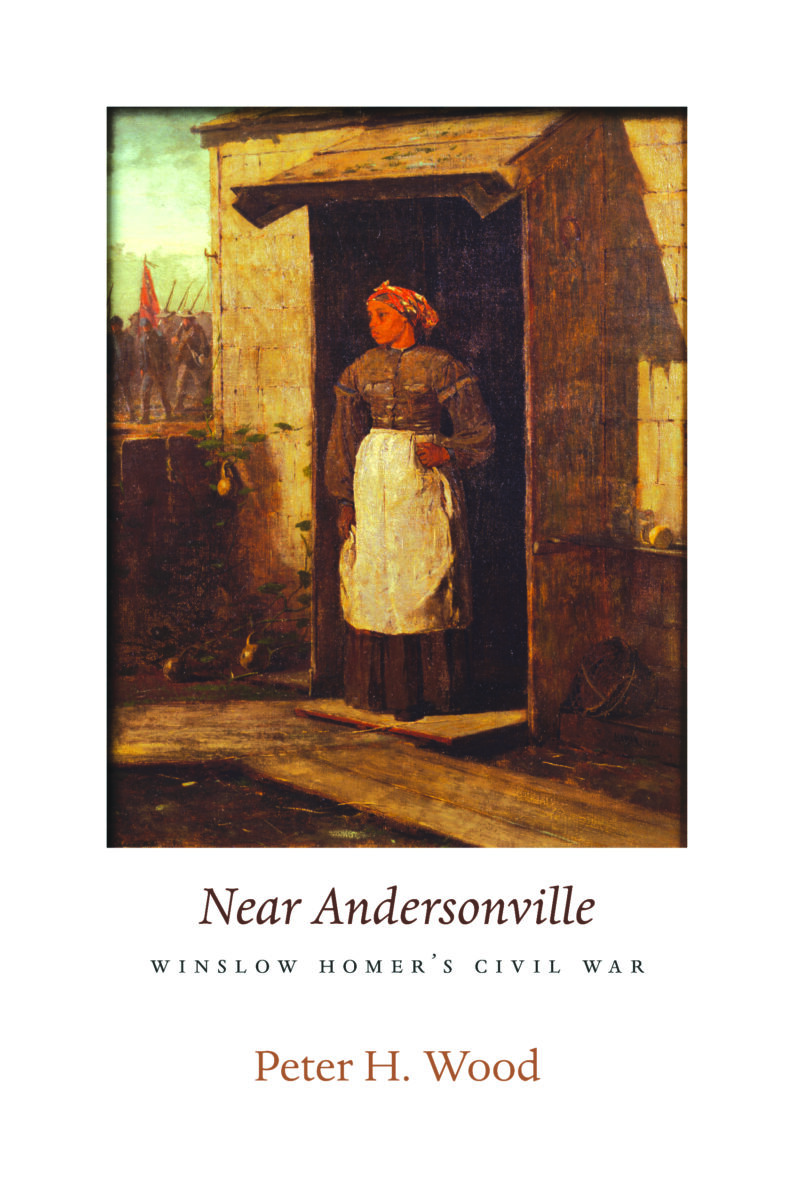

Peter Wood’s incisive new book asks us to set aside imagery of battles and soldiers, and even “Honest Abe,” so that we might visualize the world captured by the painter Winslow Homer in his long-forgotten masterpiece “Near Andersonville.” The basic compositional elements of this striking painting are not hard to decipher. Dominating its center is a black woman, presumably a slave, standing at the doorsill of a building in the midst of the countryside. She gazes toward the left of the canvass toward Confederate troops who march at the distance, carrying with them Union prisoners-of-war captured late in 1864. As we look upon her, looking upon others, a central question stands out: what did slavery’s victims make of the pageantry of a war that would revolutionize American society?

Wood deploys his considerable story-telling skills to probe the deeper intricacies of this painting’s history and meaning. He begins with a detective story and details his part in investigating the provenance of a painting discovered among family heirlooms a century after the events it portrayed. Several “eureka” moments move this narrative along and memorably dramatize the laborious process of historical reconstruction. More than in other parts of the volume, readers here are likely to have the sense of listening in on the 2009 Nathan Huggins lectures at Harvard University, which was the occasion for Wood to write this book in the first place.

Having clarified the painting’s early ownership and its original title, Wood assesses the vignette within Homer’s wartime corpus of images. As a distinguished Homer scholar, Wood deftly touches upon significant biographical details and establishes the illustrator’s sense of irony and his penchant for multiple meanings. He shows how “Near Andersonville” would have evoked a more powerful, and more complex, response than the titles “At the Cabin Door” or “Captured Liberators,” two titles that late twentieth curators inaccurately bestowed upon the work. For those coming for the first time to one of America’s greatest artists, and of his coming-of-age during the Civil War, these pages may be the most valuable of the book.

It comes as no surprise that Wood also displays his mastery of African-American history in this slim book’s concluding second and third chapters. His discussion of racial imagery in the Northern imagination of the 1860s is first-rate, as is his concluding invitation for readers to visit what he terms “The Woman in the Sunlight” at her home at the Newark Museum in New Jersey. Even as he turns to the details of the gourds, and other utensils included in the canvass, Wood writes with unmatched authority about the import of forgetting, and of then recalling, episodes from African-American history. It is not just a matter of seeing the 1860s differently, but of refiguring U.S. history in a more basic sense.

Conjecture plays an increasingly important role in Wood’s interpretation of this painting’s more subtle elements. His connection between various images and the election of 1864 depends upon his (and perhaps Homer’s) conceit of using two planks at the bottom to refer to the stand-off between Abraham Lincoln (and his party’s platform) and the Democratic Party’s George McClellan. Not all readers will be convinced by what is an admirably imaginative interpretation. (Though I found this to be more credible than the assertion that the woman was pregnant.) Among those who have critiqued Wood for overreaching evidence in forming his conclusions are Christopher Benfey, in an article written for the March 24, 2011, New York Review of Books entitled “Winslow Homer: The Stern Facts.”

To be fair, we should remember Wood’s gambit here and to appreciate the conventions that separate the lecture format from the monograph. When he engages in speculation, he seem far less concerned about convincing than provoking, less intent on establishing an iron-clad argument than in engaging our imaginations, and to open up issues rather than to pin them down. In this, his book succeeds, and it does so in a way that nearly all readers, regardless of their previous interest in the Civil War or slavery, will find supremely entertaining.

Robert Bonner is an Associate Professor of History at Dartmouth College.