This is the kind of book that academic historians ridicule, general Civil War readers find too narrow, and Gettysburg junkies embrace.

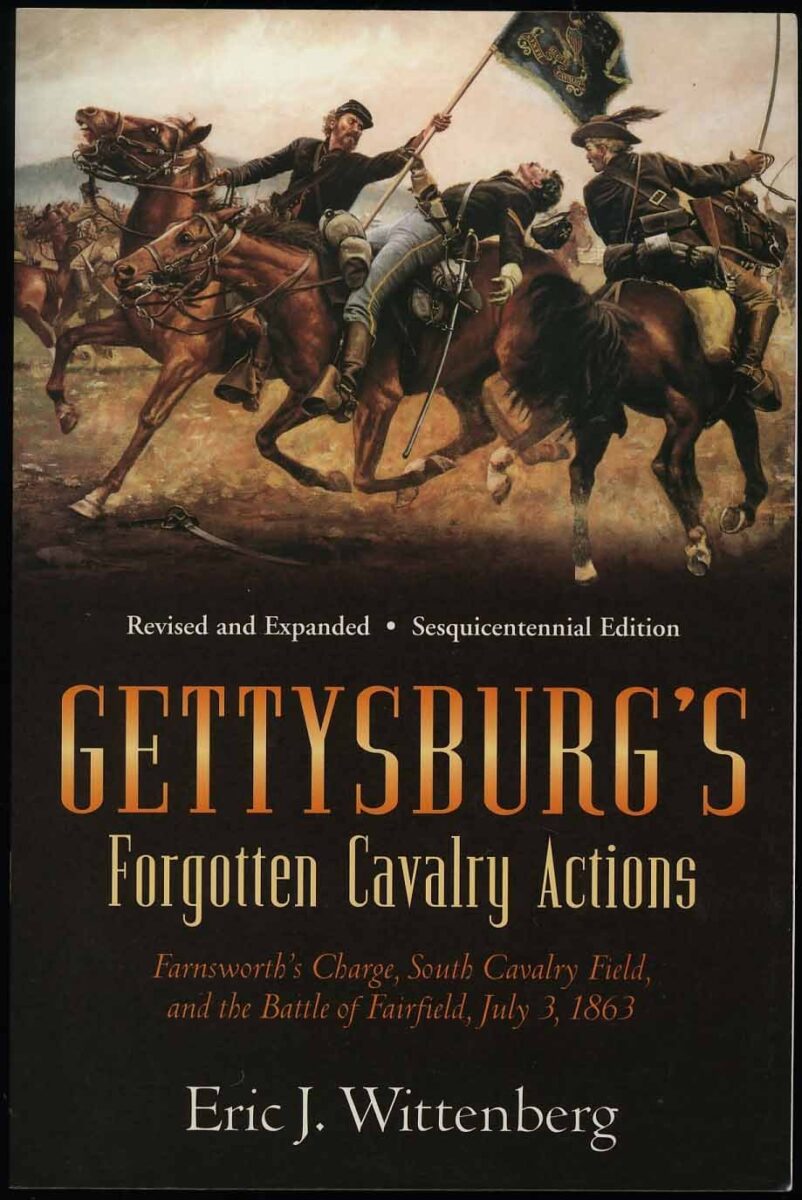

Gettysburg’s Forgotten Cavalry Actions is a revised edition of cavalry expert Eric Wittenberg’s first book, published originally in 1998. As the full title suggests, Wittenberg focuses on three engagements that occurred on Gettysburg’s final day. Readers are reminded frequently that each of these battles has been overlooked by historians, neglected by the National Park Service’s interpretation of the battlefield, and underappreciated for their potential significance.

There is little doubt that at least the first two of these assertions are true. Wittenberg’s monograph is the only book-length treatment of the three attacks launched by the cavalry brigades of Elon J. Farnsworth and Wesley Merritt on July 3, 1863, although the battles’ participants left a reasonably fulsome literature behind and a number of writers have examined these engagements with article-length studies. Visitors to Gettysburg National Military Park will find little emphasis on either Farnsworth’s or Merritt’s attacks at the south end of the battlefield and except for a couple of lonely markers, the Fairfield Battlefield is unpreserved and uninterpreted.

Wittenberg unearthed a wide variety of sources in the preparation of his book. This exhaustive research suggests that thanks to Wittenberg, there is little more to say about the tactical conduct of these small engagements. General Judson Kilpatrick emerges as the vainglorious and reckless leader of tradition in masterminding a flawed offensive that led to the needless death of Farnsworth, a promising young cavalry officer. The more respected Wesley Merritt receives deserved criticism for sending a single regiment, the 6th U.S. Cavalry, to its demise at Fairfield on the strength of a single unverified civilian report.

More controversial is Wittenberg’s claim that had Kilpatrick and Merritt conceived and executed their assaults more effectively, they possessed “an opportunity to destroy Lee’s army…on the afternoon of July 3” (150). Indulgence in counterfactual history is, of course, a cottage industry among Civil War enthusiasts, particularly students of Gettysburg. Speculating on the impact of actions that did not occur can be as intellectually stimulating as it is historically improvable.

Readers can decide for themselves if they agree with Wittenberg’s proposition that had Kilpatrick focused on turning the Confederate right flank southwest of the Emmitsburg Road with both Farnsworth and Merritt and had army commander George G. Meade subsequently unleashed a massive infantry counterattack following the repulse of the Pickett-Pettigrew assault, the Army of Northern Virginia would not have recrossed the Potomac intact. The author’s suggestion that had Merritt deployed his entire brigade at Fairfield and then taken position at Monterey Pass “the decisive battle of the Civil War” would have resulted deserves similar contemplation (150).

Many writers succumb to endowing their topics with exaggerated significance. Wittenberg’s arguments in this case descend into special pleading that, in the end, may leave readers unconvinced. The lack of contingency possessed by these little cavalry actions (against Confederate infantry at South Cavalry Field) likely explains why they have been “forgotten” in the first place.

Wittenberg writes well and one wishes that he had opted to let his own prose carry more of the story rather than inserting endless short and block quotations throughout the text. This style interrupts the narrative flow, resulting in a somewhat choppy read. He provides excellent profiles of the stories’ major figures but perhaps a bit too much biographical information regarding the bit players—digressions that again compromise a smooth narrative. The illustrations are numerous and very helpful although the maps don’t always label important topographical features mentioned in the text, such as the one-hundred foot hill and the Devil’s Kitchen.

Four appendices enhance the book. In addition to the obligatory Order of Battle, Wittenberg presents detailed walking and driving tours of each of the three battlefields he chronicles. Given that this book’s core audience of Gettysburg aficionados often enjoys visiting the field, such tours increase the reason for owning it. The only quibble from this Luddite reviewer is that in addition to providing GPS coordinates to guide tour-takers, maps of the tour routes would be helpful to those without navigational devices. The final appendix succeeds in dismantling a revisionist theory as to the actual location of Farnsworth’s charge.

Despite its flaws, Gettysburg’s Forgotten Cavalry Actions fills a niche in Civil War military history. It is aimed at a particular audience, and readers who belong in that demographic will want to add it to their libraries. Wittenberg’s work stands as the definitive study on its topics and, no doubt, Gettysburg enthusiasts will enjoy debating the author’s contention that in these neglected skirmishes at the end of the war’s most famous battle, great possibilities lay dormant.

A. Wilson Greene is the Executive Director of Pamplin Historical Park and the National Museum of the Civil War Soldier in Petersburg, Virginia.