In Virginia’s “Historic Triangle” of Jamestown, Williamsburg, and Yorktown, colonial and revolutionary history far outshine the area’s role in the Civil War. Further, when one considers the role of African Americans in the Civil War, the services of Union black troops most readily come to mind. Yet the area witnessed slaves playing a major role in bringing about their liberation, even before they were recruited to fight as Union soldiers. Today the possibility of commercial land development threatens to further obscure this rich and important history.

In May 1862, General George B. McClellan had heavy siege guns aimed at the Rebel lines at Yorktown—earthen defenses largely built by slaves pressed into Confederate service. For a month, his attempt to capture Richmond by way of the Virginia Peninsula had been stalled by his overestimation of Confederate troop strength and by these extensive fortifications. At long last, however, McClellan was set to bombard them.

However, runaway slaves on the Peninsula told Union soldiers that southern troops would not be there for the attack. Most northern officers distrusted such reports and chose to ignore them, but the African Americans were correct. Despite the strength of his defenses on the Peninsula, Confederate commander Joe Johnston wanted to rely upon Richmond’s stronger fortifications, stretch Union supply lines, and mire the Union army in the Chickahominy swamps. By May 4 the Rebels were gone, ruining McClellan’s plans for a decisive battle at Yorktown as in the Revolution. If the Yankees had heeded the news brought in by African Americans, the Army of the Potomac might have pounced on the retreating Rebels. Union officers would not make the mistake of ignoring black informants again.

As the Confederates withdrew, the Peninsula’s notoriously poor roads slowed their movement. To buy time, Johnston sent soldiers to guard the army’s retreat by setting up a defensive line that incorporated several earthen fortifications that black laborers had helped construct and that blocked the junction of two roads east of Williamsburg.

Fortunately, 16 slaves who had been forced to work on these fortifications came to Union lines and explained that there were forts on the Confederate left that were unoccupied. Other slaves brought in similar reports and revealed that if Union troops filled the empty works they would be in a protected position on the flank of the Confederate army. Even more fortuitous, one slave knew of a hidden path that led right to the empty works.

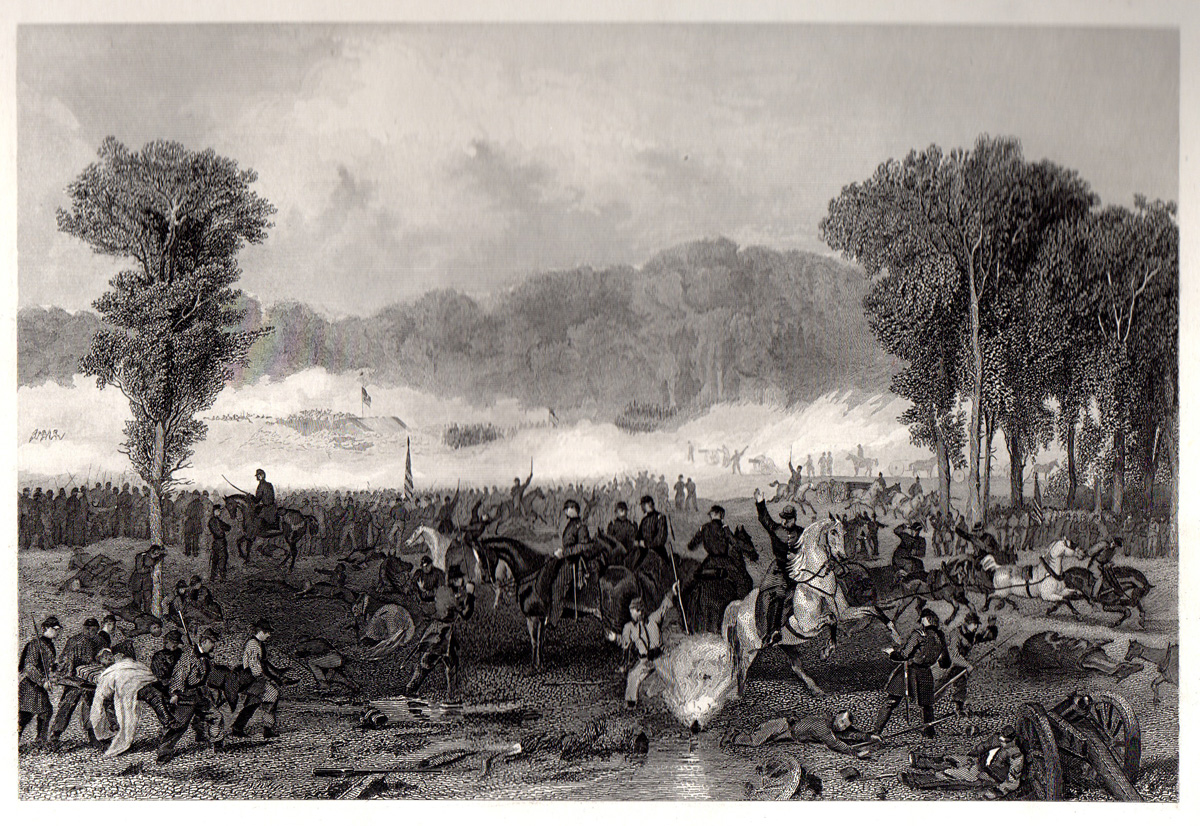

Once Union attacks elsewhere stalled, Union commanders finally decided to send at least one brigade down the secluded trail. General Winfield Hancock was ordered to occupy the abandoned Confederate works but not to move his brigade any farther without orders. The path was narrow and at times the men had to hack their way through dense foliage. For the last leg, the slaves led the Yankees across a mill dam, as well as a gorge that pond water had sliced into a hillside. Eventually the brigade emerged from the wooded labyrinth and found the works abandoned, just as the slaves said they would be.

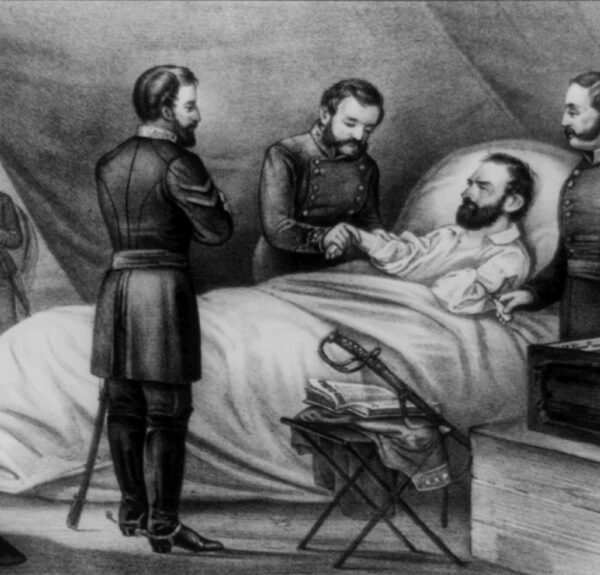

Confederate troops appeared unaware of Hancock’s arrival on their flank and the Union general quickly grasped the tactical advantage. Unfortunately, he could not get his superiors to approve an attack and received orders to withdraw. Risking a charge of insubordination, he delayed carrying the order out, but at shortly past five o’clock he reluctantly began to abandon the position.

Just then, Hancock saw that the Confederates were moving in his direction. The Rebels finally noticed the threat and sent a brigade to protect their left, rashly charging the fort. From their protected position, Hancock’s soldiers let loose a merciless barrage of musket fire that decimated the Confederate troops, reeling them backward. Hancock then ordered his men to charge. Rushing forward, the Yankees bayoneted a few Rebels and then the other southerners fled wildly for the rear. Hancock’s men completely routed the Confederates and brought in the first Rebel flag captured by the Union’s Army of the Potomac. Peninsula slaves had made the brigade’s success possible by pointing out the tactical advantage that placed the Yankees in a protected position on the enemy’s flank.

As the Union army continued its advance on Richmond, northern newspapers recognized the aid of African Americans. “Our armies have hardly taken a step,” The New York Times claimed, “without reliance upon the reports of the faithful black fellows, whose accuracy has been remarkable.”

When the Battle of Williamsburg took place in 1862, white northerners were bitterly divided over the issue of whether the government should attempt to liberate the slaves. When the Civil War began, most white northerners felt that the war’s only aim should be to keep the South from seceding, not to end slavery. Yet, after a year of conflict those sentiments were changing. It had become obvious that the South was effectively forcing its slave population to build earthen fortifications (like those around Yorktown and Williamsburg) that slowed the advance of Union troops. At the same time, however, black southerners had also proven their desire to help the North win the war, and their services (as in the Battle of Williamsburg) had become invaluable to northern armies.

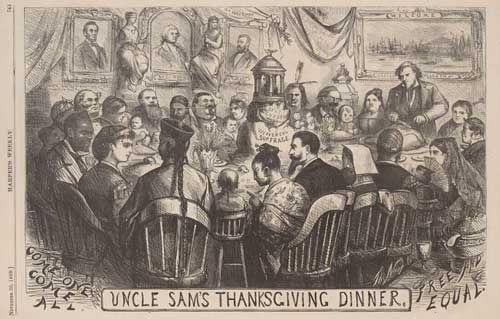

Both of these considerations ultimately played a large role in the federal government’s decision to turn the war into one that freed the slaves. Those that favored emancipation repeatedly pointed to the events that transpired on the Virginia Peninsula to make their case, and these factors figured greatly in President Abraham Lincoln’s deliberations over the Emancipation Proclamation. By the start of 1863, African Americans were finally being recruited as soldiers. Thus, the African Americans around Yorktown and Williamsburg that had built Confederate fortifications, and then helped Union forces use them to their own advantage, had played a significant role in changing the nature of the Civil War.

Today, the land on which this significant portion of the Battle of Williamsburg occurred is largely untouched (though more wooded). Part lies within the boundary of the National Park Service’s Colonial Parkway, but most is on undeveloped land owned by Anheuser Busch and a local family. Both groups are trying to get a “mixed-use overlay” applied to the land, making it vulnerable to development that would utterly destroy its historic significance. Such an occurrence would be shameful, further obscuring the area’s role in the Civil War. Perhaps more important, it would destroy one of the few battlefield sites that clearly demonstrates the roles that African Americans played (before they were recruited as soldiers) in helping to change the war into one that brought freedom to the enslaved. Hopefully, those seeking to preserve both Civil War and African-American history will rise up and help the Williamsburg Battlefield Trust win this current battle of Williamsburg.

Glenn Brasher is an instructor of history at the University of Alabama and winner of the 2013 Wiley-Silver Prize from the Center for Civil War Research. For more information on the battles around the “Historic Triangle,” see his book The Peninsula Campaign and the Necessity of Emancipation: African Americans and the Fight for Freedom.

Illustration courtesy of the Library of Congress (loc.gov).

To learn more about the Williamsburg Battlefield Trust and their mission, please visit their website at http://williamsburgbattlefieldtrust.org/eggerbusch.html.