The topic of so-called “Black Confederates” is controversial. Some insist that Confederate nationalism motivated thousands of African Americans to fight alongside their masters, proving that slavery did not cause the American Civil War. The Internet has become one of the primary means of spreading this nonsense. While professional historians scoff, the “black confederate myth” is popping up on monuments across the south and even temporarily appeared in a Virginia textbook.

When asked about “Black Confederates,” historians often question the sources used by the myth’s supporters, pointing out that they are usually second-hand and anecdotal, or a product of post-war Lost Cause propaganda. Other historians simply pooh-pooh the claims. I believe that these are not effective responses. A better approach is to place the evidence back into the context in which it first emerged.

In a number of primary sources, people claim to have seen African Americans fighting alongside Rebel soldiers. Most of these sightings were likely of slaves serving as body servants for their soldier masters, or were of the thousands of slaves impressed to work on confederate fortifications. Still, individual human motivations are rarely monolithic and therefore it is not irrational to believe that in the excitement of combat a few of these black men picked up weapons and got involved in the fighting. Some perhaps felt that in their particular situation it was in their best interest to demonstrate “loyalty” to their masters. Others may have been deceived about the intentions of northern soldiers; white southerners repeatedly told their slaves that Yankees were intent on capturing blacks to send them away to labor in the Caribbean.

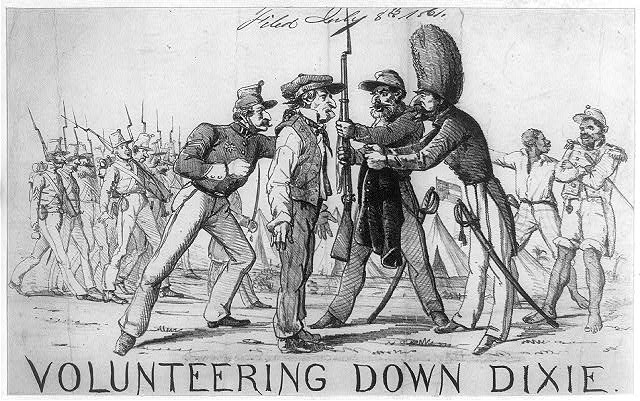

Yet while these incidences were in nowhere near the numbers that some claim today, the exaggeration of such tales to promote an agenda is not new. In pushing for emancipation, some abolitionists and radical Republicans widely publicized these stories. In propaganda-like fashion, they greatly exaggerated them to further their cause, and thus they were the first to give these reports more credence and attention than they deserved.

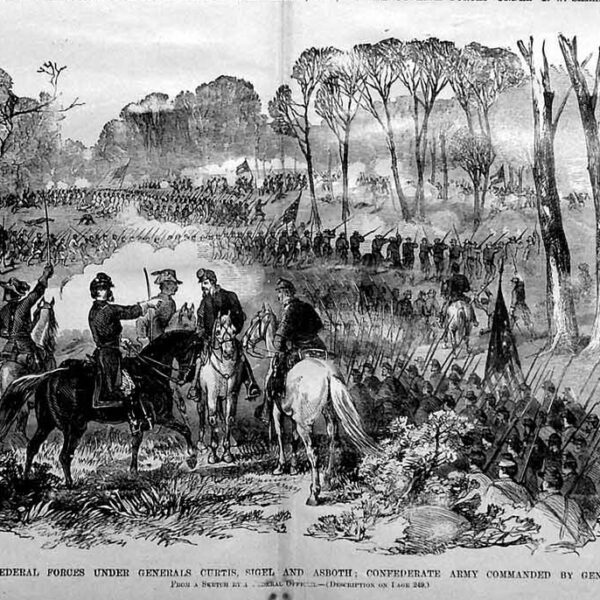

Immediately after the July 1861 battle at Manassas, Virginia, scattered news reports claimed that people saw blacks fighting there among the Confederates. The New York Times, for example, declared that “we hear of black regiments” in the Rebel army, and reprinted a story from the Richmond Enquirer heralding an “ebony patriot” who shot a Yankee officer and captured another. The Charlotte (N.C.) Western Democrat celebrated the “sable patriots” of Manassas and claimed “many cases . . . of [northern] prisoners being taken by negroes.” Some Northerner newspapers claimed that blacks had fought for the Confederates that day in significant numbers. “It is boasted that there are two well drilled regiments of negroes in [the Confederate] army” the Chicago Tribune reported. “The fact that negroes fought in the battle at Bull Run is undisputed,” one correspondent concluded after discussing the battle with Union soldiers who had been in it. “They were forced to do it, but they fought.”

Far more important than the veracity of these dubious claims, is that emancipationists used them to shape northern public opinion and Union war policy. The day before the battle, the U.S. Senate debated a bill that would allow the confiscation of Rebel property used to support Confederate armies. After the battle, Senator Lyman Trumbull proposed an amendment to the bill that broadened the definition of property liable for confiscation to include slaves. “I understand that Negroes were in the fight which has recently occurred,” Trumbull said on the Senate floor. “Negroes who are used to destroy the Union and to shoot down the Union men by the consent of their traitorous masters [should be confiscated].” While there was some objection to the amendment, news from Manassas swayed some senators. Conservative senator John C. Ten Eyck, for example, explained that he previously voted against the amendment, but now changed his mind. “Having learned and believing that [slaves] have been used and employed with arms in their hands to shed the blood of Union-loving men of this country,” he argued, “I shall vote in favor of this amendment.” The amendment and the Confiscation Act overwhelmingly passed, becoming the first legislation that allowed Union commanders to harbor runaway slaves.

To further promote emancipation as a military necessity, abolitionists continued to spread reports of slaves fighting for the Confederacy. In September 1861, famed black abolitionist Frederick Douglass maintained “it is now pretty well established, that there are at the present moment many colored men in the Confederate army doing duty . . . as real soldiers. . . . There were such soldiers at Manassas, and they are probably there still.” Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, issued a warning. “The question is not Shall there be black regiments. But, Shall they fight on our side or the side of the enemies?” If the government did not emancipate the slaves, she insisted, the North would have to fight an increasing numbers of blacks in rebel armies.

With hindsight, these fears were unwarranted. The Confederate government vehemently resisted enrolling black troops until the last months of the conflict. In fact, after the Manassas battle a Rebel officer suggested the creation of black regiments but Confederate president Jefferson Davis labeled the idea “stark madness” and claimed such an action “would revolt and disgust the whole South.”

But these were real concerns, and reports continued to come in. On December 22, for example, Confederates attacked several companies of Union soldiers during a routine reconnaissance up the Virginia Peninsula. Some soldiers claimed that blacks were among their assailants. “Many colored men were in the enemy’s ranks,” Chaplain Richard F. Fuller recorded in his diary that night, “the rebels having no tender scruples about arming the slaves.”

A day after the skirmish, the number of blacks engaged in it was inflated to promote an agenda. In a letter to The Indianapolis Journal, a Hoosier soldier made the outrageous claim that Union soldiers encountered “a body of 700 negro infantry, all armed with muskets, who opened fire.” The wounded soldiers “testify positively that they were shot by negroes.” The soldier called on the government to act; “If they fight us with negroes, why should not we fight them with negroes too?” The story soon found its way into newspapers across the north as a means of promoting emancipation.

In the early months of 1862, these stories continued to be a regular feature in the speeches and editorials of emancipationists. In pushing for both emancipation and the recruitment of black troops, an abolitionist newspaper maintained that the Confederates “have been fighting in close companionship with negroes, from the beginning!” William Lloyd Garrison maintained that Southern blacks “are at the service of the country whenever we accept them. But the Government will not accept them, and the rebel slaveholders are mustering them in companies, and in regiments.” In front of an audience at the Smithsonian Institute, Wendell Phillips insisted “if Abraham Lincoln does not have the negro on his side, Jefferson Davis will have him on his.”

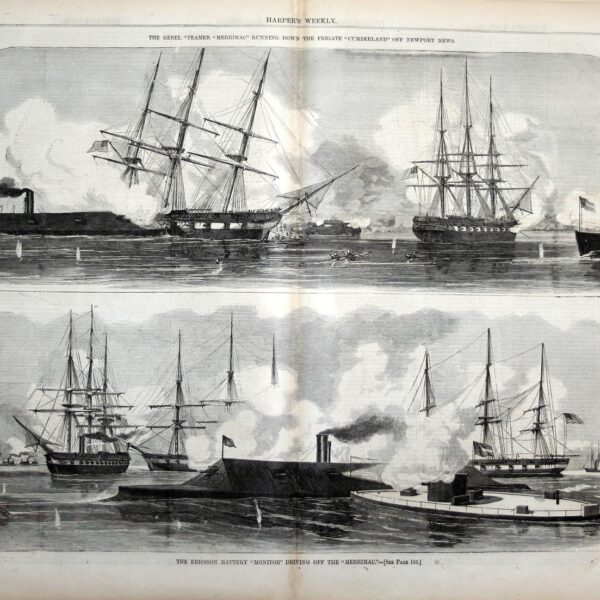

The Peninsula Campaign, the major event in the eastern theater in the spring of 1862, increased these allegations. During the Yorktown siege, for instance, Northern newspapers reported that the Confederates forced blacks to act as sharpshooters, and as artillery gunners. Both the New York Times and the Philadelphia Inquirer claimed that blacks were seen “uniformed and armed” at Yorktown, and the Baltimore American insisted they were “keeping guard as other soldiers.”

While the Peninsula Campaign was unfolding, Congress deliberated a second confiscation act that would allow for the seizure and liberation of all slaves owned by Rebels, regardless of whether the Confederacy had impressed their labor. Such legislation would potentially expand the number of freed slaves. To support the bill, these reports of black Confederate soldiers were a mainstay in the northern press and on the floors of Congress.

“Of course the . . . Democrats and the ‘conservatives,’ the Chicago Tribune editorialized, “see nothing wrong [with the Confederates] training the black man to cut up our troops, but let the proposition be made for a negro regiment in the Union service, and they start back in terror at the idea.” The editors were outraged that “slaves may . . . carry muskets for our Southern brethren” and “shoot down our soldiers under the fear of their master’s lash,” but were not allowed to fight for the Union cause. “Does not every man see,” Representative John Hickman told congress, that when the Confederates “are at liberty to employ their slaves, not only in the erection of fortifications, but . . . in the defense of [these] military works, it is a matter of necessity to deprive them of these auxiliaries?”

Radicals were not alone in making such assertions. Conservative Senator John Sherman told Congress, “The question must be decided whether the negro[s] . . . shall be employed only to aid the rebels.” Sherman insisted that Southern slaves not only performed all the army’s hardest labor, but the “rebels fight side by side with them. . . . Now, shall we avail ourselves of their services, or shall the enemy alone use them?”

“I think we can not be mistaken,” moderate Republican senator James Doolittle argued, the Confederates “have employed negroes not only upon intrenchements and in camp service, but have organized and put arms in their hands to shoot down our sons and our brothers on the field of battle.” Because of this “fact,” the senator maintained, the government should authorize the president “to employ them, and even to arm them.”

Commenting on the debates, the New York Commercial Advertiser noted that the Confederates had used their slaves “as gunners on fortifications, and as picket guards. These are ascertained facts. It is also said they have some negroes enrolled in regiments.” The Commercial’s editors found it “refreshing” that “the recent debates in Congress indicate a definite policy” which would begin to deprive the South of their black laborers. The prediction proved accurate: at the end of July 1862 Congress passed the Second Confiscation Act, and Lincoln presented the Emancipation Proclamation to his cabinet.

I am not suggesting that these reports of so-called “black confederates” were the primary reason why many northerners came to embrace emancipation. However, they clearly played a significant part in the debate, and yet historians rarely, if ever, present or acknowledge these claims when discussing emancipation. As a result, they have fallen into the hands of “neo-confederates.” It is profoundly ironic that modern Confederate apologists now use these emancipationist exaggerations to support their own interpretations of southern motives.

To successfully combat the “black confederates myth,” historians should not simply explain away these accounts. Rather, we should take them out of the hands of those who attempt to use them to glorify the Confederacy, put them back into the context of the emancipation debate in which they first appeared, and in doing so reveal their true importance. While these sightings of so-called “Black Confederates” do not prove African American support for the Confederacy, they do illuminate one largely unexplored reason why Northerners came to embrace emancipation as a war aim.

Glenn David Brasher is the author of The Peninsula Campaign and the Necessity of Emancipation (2012) and winner of the 2013 Wiley-Silver Prize from the Center for Civil War Research.

Sources: Douglass’ Monthly IV (September, 1861): 516; Charlotte Western Democrat July 30, August 6, 1861; Chicago Tribune, July 29, 1861, March 19, 1862, May 29, 1862; Congressional Globe, 37th Congress, First Session, 218-219, 1484; Congressional Globe, 37th Congress, 2nd Session, 1801, 3198-99, 3229-30; Richard F. Fuller, Chaplain Fuller; Being a Life Sketch of a New England Clergyman and Army Chaplain (Boston: Walker, Wise, 1863), 232; Indianapolis Journal, December 27, 1861; Bruce Levine, “Black Confederates,” North and South 10:2 (July 2007): 42; Liberator, August 23, 1861; National Anti-Slavery Standard, August 3, 1861; New York Commercial Advertiser quoted in Cincinnati Gazette, July 15, 1862; New York Times, January 14, 1862, April 27, 1862; Philadelphia Inquirer, April 25, 1862; Principia, September 21, 1861, January 30, 1862.

Related topics: African Americans, Confederacy