Actually, he didn’t do a lot of things. For starters, he didn’t lead a guerilla army against Federal invaders/occupiers—even though more than a few people suggested that he take that course of action. Second, he didn’t pick up and leave the country for Canada or Mexico. Finally, and most important, he didn’t take a public stance against the United States. He never once publicly uttered a single hostile or defiant word against the nation that had destroyed the Confederacy.

Following the logic of Lee mythology, his conciliatory position makes a lot of sense. In terms of reflecting on Lee the commanding general, admirers, apologists, and biographers have often noted that Lee could only refer to Federals as “those people.”1 This benign phrase elevates Lee above the base hostility freely exhibited by many of Lee’s contemporaries in the Confederate army who openly hated their enemies. “Those people” almost seems kind of nice, suggesting that Lee had a job to do to be sure but didn’t really have any hard feelings against the Union army. But this is the stuff of myth and does not really reflect the truth. Lee had plenty to say about his enemies—and much of it was negative. He called them vandals, miscreants, and other things illustrating his animosity. He was appalled by the Federal occupation of his home at Arlington and entirely disgusted with the Emancipation Proclamation. The list goes on and on, but rather than belabor the point I will just conclude that Robert E. Lee was not fond of Yankees.

So much for mythology. But Lee’s conciliation makes sense for another reason. His sense of duty dictated his actions both in war and in peace. Lee understood with crystal clarity that the Confederate nation went to war and lost on the battlefield. Lee’s duty as the leader of a defeated army was to abide by the terms set forth by the victorious party. The best thing Lee could do for the South was to work for a peaceful reunion, which meant he kept all personal feeling of bitterness animosity (and there were plenty) private.

Lee counseled his former subordinates to follow in his conciliatory footsteps. He even reined in cantankerous unreconstructed types like Jubal Early, a former Confederate general who specialized in inflammatory language, letting him know that “we shall have to be patient and suffer for a while at least—all controversy will only serve to prolong angry and bitter feelings and postpone the period when reason and charity will resume their sway.”2 While serving as president of Washington College in Lexington (Lee also felt it his duty to take up substantive work) he offered the same advice to his students and would reprimand any of those who would derisively refer to their northern countrymen as “Yankees.” He did so for practical reasons—to insure that there were no ill feelings between the sections that could “injure the institution.”3

Privately, Lee was an angry man who was very unhappy about how things had turned out. Writing his cousin Annette Carter in 1868 he had this to say about the current government. He wrote of “this grand scheme of centralization of power in the hands of one branch of the Govt. to the ruin of all others and the annihilation of the constitution, the liberty of the people and of the country.”4 Continuing, Lee said: “I grieve for posterity, for American principles and American liberty. Our boasted self govt is fast becoming the jeer and laughing stock of the world.” In 1870, he spoke to William Preston Johnston (Albert Sidney Johnston’s son and a colonel in the Confederate army who had been captured with Jefferson Davis in 1865) of the “vindictiveness and malignity of the Yankees, of which he had no conception before the war.” 5

The truly remarkable thing is that he was a great conciliator despite his personal feelings. And it is the conciliator Lee—or rather, what Lee didn’t do—that is remembered in our nationalist culture, North and South.

M. Keith Harris, who holds a Ph.D. in U.S. History from the University of Virginia, hosts the blog Cosmic America: Civil War History and Memory.

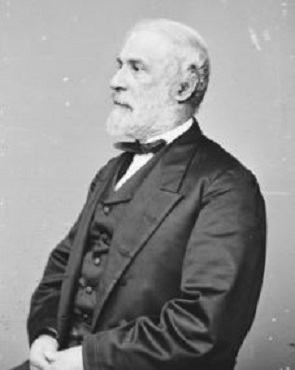

Image Credit: Library of Congress.

Notes:

1. Douglas Southall Freeman, Lee’s great champion and biographer, cites numerous occasions where Lee used this phrase to describe his enemies. See, Freeman, R. E. Lee 4 vols (1935; reprint, Scribner, 1978),3:25, 202, 321.

2. Robert E. Lee to Jubal A. Early quoted in Robert Edward Lee, Recollections and Letters of General Robert E. Lee (New York: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1909), 220.

3. Thomas Nelson Page, Robert E. Lee: The Southerner (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1909), 272.

4. Robert E. Lee to Annette Carter quoted in Richard B. McCaslin, Lee in the Shadow of Washington (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2001), 212.

5. Robert E. Lee to William Preston Johnston quoted in Thomas L. Connelly, The Marble Man: Robert E. Lee and His Image in American Society (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1977), 212.

Lee’s “sense of duty” included him being unable to determine when the war was over, resulting in thousands of unnecessary deaths. Haven’t we heard enough about this traitor?