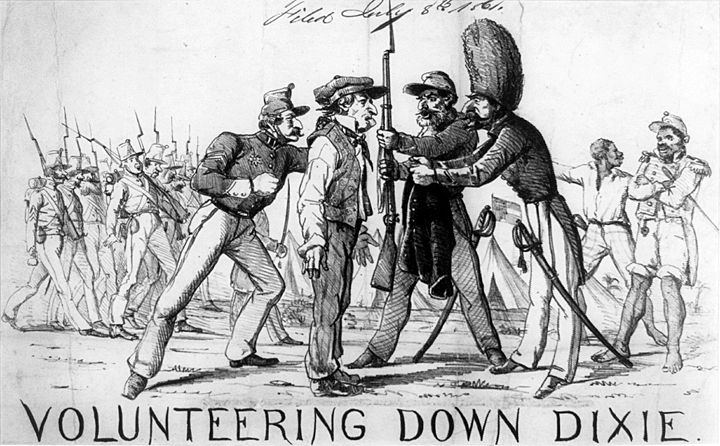

Last week brought the sesquicentennial of the first Confederate Conscription Act. The draft would later become a particularly divisive element in the Confederacy (as it also became in the North), especially after the law was amended to exempt large slaveholders. (“Rich man’s war, poor man’s fight,” etc.) But initially, some saw it favorably. I was intrigued to find this editorial, arguing that the draft was not only necessary, but a positive step toward justice in spreading the burden of military service among the citizenry.

From the April 29, 1862 Galveston Weekly News:

The Confederate Congress has passed an act, based upon the recommendation of the President, to organize a system of drafting or conscription for the army. The provisions of this law includes all residents between the ages of 18 and 35 years, and requires the enrollment of 300,000 additional recruits of conscripts. The object of this radical change in our military system is not to discourage the formation of volunteer corps, or to dampen the ardor of out citizen soldiery, but to regulate both. The regiments now in service have had their numbers diminished by sickness and the accidents of war, and volunteers, instead of filling up these skeleton formations, prefer a new organization, and their own elected officers. The system pursued thus far threatens to involve the Government in the enormous expense attended the support of mere shadows of regiments – officers without men – and on the other hand brings the fresh troops into the field without the advantage of disciplined and experienced commanders. If this war was to last for a few months only, or to be terminated without maneuvers or tactical skill, by the mere onset of brave men, if might be well to leave it to the native valor of our people, without further care; but it promises to be long, arduous, and to be maintained only by the strategy of our generals and the steadiness of our troops. Let us, then, wisely preparing for the future, look to the necessities of a contest, which will require all our exertions and all the sacrifices which a people, confident in their right and in ultimate success, may reasonably make. . . .

Whatever objections may be urged against [conscription], as incompatible with our notions of American liberty, they have no weight with us in such a time as this. We are now involved in a war for our very existence, and if we would secure success beyond a peradventure, and bring the war to a speedy close, we must make war business, and have recourse to all the most effectual appliances that have stood the test of experience. We have seen the objections urged that it is derogatory to the character of Americans, as well as inconsistent with the genius of our free government, to force men into military service against their own consent. . . , [but] it might with just as much propriety and force of argument, be said that Americans ought not to be forced, in time of peace, to pay taxes, but that the government should depend on voluntary contributions. The truth is, equal burthens and equal benefits is a cardinal principal in American liberty; and this equality is totally lost sight of whenever the government looks to the people for voluntary support, either in peace or war. All patriotic and charitable enterprises undertaken by voluntary contributions are always very unequal, those often contributing most who are the least benefited and vice versa. We do not think this war should be supported in that way. We know a very large majority of our citizens are ready and willing to volunteer; but there are those among us all over the country, who will find some excuse to avoid military service, which is now our sole dependence, and these men are often those who have most at stake, and who will be most benefited by the achievement of our independence.

We think it injustice towards the more patriotic class of our citizens, that our government should have adhered to the volunteer system which throws all the perils, privations and hazards of life upon them alone, while the unpatriotic are permitted to remain at home and reap the benefit of their successful battles, and perhaps, speculate on their misfortunes.

What’s remarkable here is that this is, in principle, the same argument that modern day dyed-in-the-wool liberals make for universal conscription—that done fairly, it’s an equitable way to spread the burden of war across society and to fully mobilize that society in support of the military effort. The argument made by the person who penned this editorial in the Galveston Weekly News 150 years ago resonates today. That anonymous writer would have immediately understood the political terrain of the draft debate in the present-day United States. Opposition to the draft, both in the 1860s and in the 1960s, gained much of its force from the obvious inequities and loopholes. During the Civil War, there was widespread anger (in the North and the South) over allowing paid substitutes to fulfill a man’s military obligation or offering large slaveholders exemptions from Confederate military service. During Vietnam, opposition to the draft stemmed from the way it was being implemented in a bloody and deeply unpopular war; there were seemingly endless college deferments and safe, stateside appointments to the National Guard and Reserve for those young men with connections. Americans’ opposition to the draft, in both the 19th century and the 20th centuries, had less to do with the principle of conscription, and more to do with its uneven application.

Plus ça change, y’all.

Andy Hall is a Texan and Southerner by birth, residence and lineage, with a family tree full of butternuts. With a background in history, museum studies and marine archaeology, Hall also writes at his own blog, Dead Confederates.

Image Credit: Library of Congress.