Good afternoon. In honor of the Battle of Hampton Roads, we bring you another Voice from the Past—this time from the Union perspective. The following is Commander S. Dana Greene’s account of the battle as printed in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War:

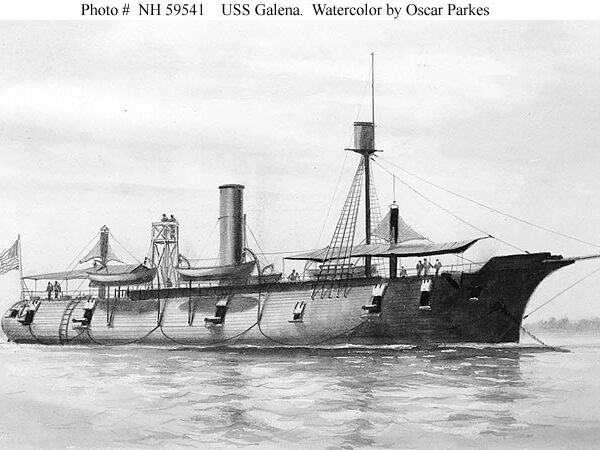

The keel of the most famous vessel of modern times, Captain Ericson’s first iron-clad, was laid in the ship-yard of Thomas F. Rowland, at Greenpoint, Brooklyn, in October, 1861, and on the 30th of January, 1862, the novel craft was launched. On the 25th of February she was commissioned and turned over to the Government, and nine days later left New York for Hampton Roads, where, on the 9th of March, occurred the memorable contest with the Merrimac…

The physical condition of the officers and men of the two ships at this time was in striking construct. The Merrimac had passed the night quietly near Sewell’s Point, her people enjoying rest and sleep, elated by thoughts of the victory they had achieved that day, and cheered by the prospects of another easy victory on the morrow. The Monitor had barely escaped shipwreck twice within the last thirty-six hours, and since Friday, morning, forty-eight hours before, few if any of those on board had closed their eyes in sleep or had anything to eat but hard bread, as cooking was impossible. She was surrounded by wrecks and disaster, and her efficiency in action has yet to be proved.

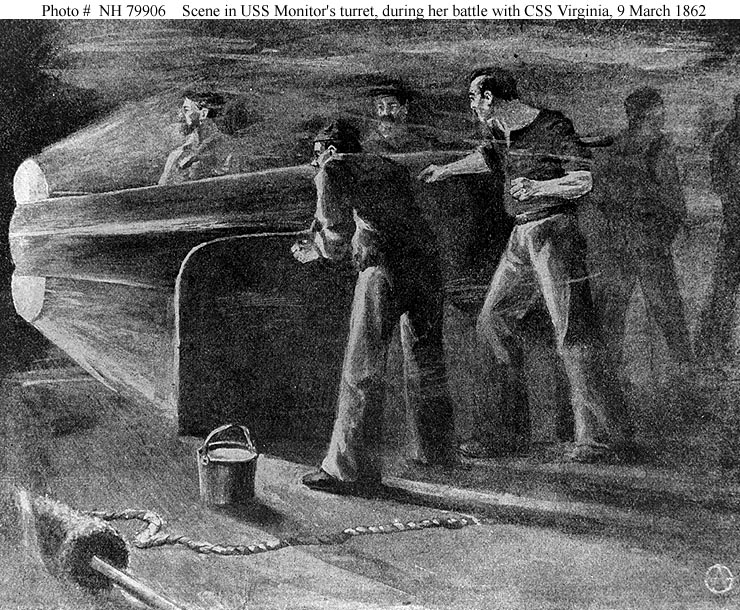

Worden lost no time in bringing it to test. Getting his ship under way, he steered direct for the enemy’s vessels, in order meet and engage them as far as possible from the Minnesota. As he approaches, the wooden vessels quickly turned and left. Our captain, to the “astonishment” of Captain Van Brunt (as he states in his official report), made straight for the Merrimac, which had already commenced firing; and when he came within short range, he changed his course so as to come alongside of her, stopped he engine, and gave the order, “Commence firing!” I trice up the port, ran out the gun, and, taking deliberate aim, pulled the lockstring. The Merrimac was quick to reply, returning a rattling broadside (for she had ten guns to our two), and the battle fairly began. The turrets and other parts of the ship were heavily struck, but the shots did not penetrate; the tower was intact, and it continued to revolve. A look of confidence passed over the men’s faces, and we believed the Merrimac would not repeat the work she had accomplished the day before.

The fight continued with the exchange of broadsides as fast as the guns could be served and at very short range, the distance between the vessels frequently being not more than a few yards…

Our shots ripped the iron of the Merrimac, while the reverberation of her shots against the tower caused anything but a pleasant sensation. While Stodder, who was stationed at the machine which controlled the revolving motion of the turret, was incautiously leaning against the side of the tower, a large shot struck in the vicinity and disabled him. He left the turret and went below, and Stimers, who had assisted him, continued to do the work…

The battle continued at close quarters without apparent damage to either side…

Two important points were constantly kept in mind; first, to prevent the enemy’s projectiles from entering the turret through the port-holes,-for the explosion of a shell inside, by disabling the men at the guns, would have ended the fight, as there was no relief gun’s crew on board; second, not to fire into our own pilot-house. A careless or impatient hand, during the confusion arising from the whirligig motion of the tower, might let slip one of our big shot against the pilot-house. For this and other reasons I fired every gun while I remained in the turret.

Source: Greene, S. Dana. “In the “Monitor” Turret.” Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Volume 1. New York: The Century Co., 1887.

Image Credit: Naval Historical Center’s Online Library of Selected Images.