Library of Congress

Library of CongressMembers of the Grand Army of the Republic and the Daughters of Union Veterans gather in Colorado in the 1930s.

In July 1883, thousands of former Union soldiers in the East and Midwest boarded railroad cars bound for Denver, Colorado, to attend the Seventeenth National Encampment of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), the largest and most powerful Union veterans organization. It was the first time a western state had hosted such an event, with the Centennial State (nicknamed for its admission in 1876) beating out such contenders as Nevada and California. The choice of Colorado might have struck some of the visiting veterans as curious; they were headed to what had been a territory when they first shouldered their muskets in 1861 or finally marched home from Appomattox in 1865. But they enjoyed day trips into the Rockies, marveling at mountains so hugely different from peaks in the Appalachian and Allegheny ranges they may have traversed during the war.

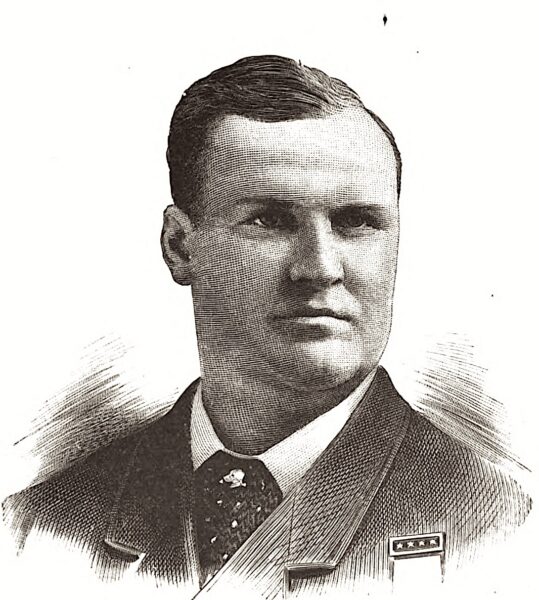

“The land where our weary feet have halted in the march to the final roll call was almost a wilderness when the war began,” GAR Commander Paul Vandervoort said in addressing the assembly. “Its mineral wealth was yet untouched,” he continued, “its plains were untilled. Its quarries were unopened. Its fountains of eternal youth unfrequented save by the wild savage.” Vandervoort, the first enlisted soldier to rise to the rank of commander in chief in the GAR, believed that Union victory in the Civil War had thrown open the gates to the American West: “It is a happy thought that this progress, this onward movement of the car of fortune, this red flame of the torch of liberty, the glory of civilization, the triumph of education, the wonders of the exposition, would not have been possible had it not been for the victories of the Grand Army of the Republic.” Vandervoort’s remarks made clear the ferocious belief in American Manifest Destiny, with only an oblique reference to the savage cost of that conquest.

History of the Grand Army of the Republic (1889)

History of the Grand Army of the Republic (1889)GAR Commander Paul Vandervoort

Other speeches offered the veterans a platform for incorporating the region into their memories of the war. All was in the spirit of reunion and reconciliation—suggesting that the West was the ideal space for letting bygones be bygones, for doing the work of binding up the nation’s wounds, for moving toward modernity and away from the barbarity of internecine war. Such sentiments were hard to disguise, especially when Governor James Benton Grant rose to welcome the 10,000 veterans gathered in his capital city—some of whom he might have faced across the battlefield in his time as a private in the 20th Alabama Light Artillery, CSA. “The bitterness of the past is over,” Grant said in welcome to the veterans. “[W]e are here in Colorado endeavoring to build up a great state … not as Northern and Southern men, not as Federal or Confederate soldiers, but as brethren of an undivided household.” At Governor Grant’s urging, sectional divisions were set aside, and attendees gloried instead in the progress made by the West in the nearly 20 years since the end of the conflict.

Throughout that first GAR reunion in the West, dignitaries seized the dais to promote reconciliation between North and South while occupying land that had been violently wrested from Indigenous peoples for decades. And no gestures were made, by anyone empowered to speak on behalf of the veterans, toward reconciling with Native Americans. Historians know that Union victory came at a heavy price for the South—some 258,000 Confederate deaths (at lowest estimates), $1.4 billion in physical capital, $2 billion in the value of enslaved peoples freed by the war. Contemporaries could not ignore the destruction—monetary or physical. Rebuilding took time, even generations, but white southerners recouped their losses and faced few obstacles in reclaiming their lands and livelihoods. One such southern citizen was now the governor of Colorado. Reconciliation benefited the former Confederacy, whether it took place in the South or the West.

Not so for Indigenous peoples, whose losses over the same period of Union ascendancy remain unquantifiable. It is especially hard to figure the value of their losses related directly to the Civil War, beyond the infamous incidents at Mankato, Bear River, or Sand Creek. There are no photographs of buildings hollowed out by cannon fire, or miles upon miles of twisted railroad ties, to suggest how destructive the war was for Native Americans. But there are maps—maps that show how wartime legislation expropriated nearly 11 million acres of land from 250 Native nations and tribes to provide the funding and physical space for land grant universities. For all that land, greater in size than the states of Massachusetts and Connecticut combined, the federal government paid less than $400,000. (Readers interested in knowing more should consult the report of High Country News, which details the billions of dollars in profit universities have continued to reap from this land scrip.)

Library of Congress

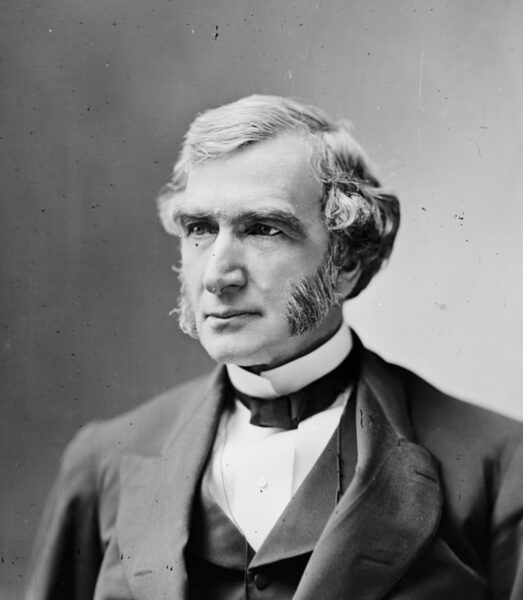

Library of CongressSenator Justin Morrill

The hope of Justin Morrill, the Vermont senator who crafted the 1862 act that established a national system of public universities, was to create “something for all who desire to own land; something for cheap scientific education; something for every man who loves intelligence and not ignorance…. [S]omething for peace.” His remarks anticipated the rhetoric of Vandervoort and Grant in Denver in 1883. The Civil War would transform the West and do so in the name of peace—between all sections, parties, and people. And it would do so without any thought of recompense. Land is simply one example, but a fair one, to show how little thought the Civil War generation gave to the price of western conquest, all why they tallied the cost of the war between the states.

By claiming the West as both a space for reconciliation and a great prize won by the conflict, the Civil War generation perpetuated the pernicious narrative that portrayed western expansion as a victimless process. The West offered the space for the nation to heal from the wounds of war, to begin anew, without reference to the animosity and antagonism of the war years (and the century of conflict over slavery that proceeded them). As a result, the region came to be associated with the salvation of democratic ideals—the place where a new birth of freedom could truly take place. It made good sense, then, that 19th-century Americans did not want to tarnish their vision of a pristine and redemptive West with the bloody reality of the cost of settler colonialism. Twenty-first-century historians must do better. We must try to understand not only how important exploring the American West was to the causes of the Civil War, but also how then exploiting the West helped the nation recover from the conflict—and mask one still not resolved.

Cecily Zander is an assistant professor of history at Texas Woman’s University and a senior fellow at the Center for Presidential History at Southern Methodist University. She is the author of The Army Under Fire: Antimilitarism in the Civil War Era (LSU Press, 2024). She is at work on a study of Abraham Lincoln and the American West, to be published by Liveright. In the fall of 2025, she will join the Department of History at the University of Wyoming.