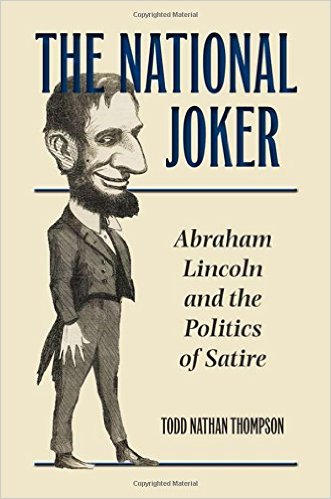

The National Joker: Abraham Lincoln and the Politics of Satire by Todd Nathan Thompson. Southern Illinois University Press, 2015. Cloth, ISBN: 976-0-8093-3422-3. $29.50.

Abraham Lincoln’s facility with words allowed him to craft some of American literature’s loftiest rhetoric; it also allowed him to connect to the most homespun of backcountry constituents. He was, says author Todd Nathan Thompson, a “beautiful writer” with a powerful “command of rhetoric.”

Abraham Lincoln’s facility with words allowed him to craft some of American literature’s loftiest rhetoric; it also allowed him to connect to the most homespun of backcountry constituents. He was, says author Todd Nathan Thompson, a “beautiful writer” with a powerful “command of rhetoric.”

While modern audiences today tend to remember “four score” and “with malice toward none and charity for all,” Lincoln’s contemporaries best recognized his rhetorical powers through a much different lens: his sense of humor, which became legendary. Thompson’s new book, The National Joker: Abraham Lincoln and the Politic of Satire, demonstrates just how shrewd and purposeful the president’s sense of humor was.

“Lincoln, time and time again throughout his political career, repurposed jokes for political ends, in the process transmuting humor into satire,” Thompson explains. A joke was seldom just a joke. Like Aesop, to whom Lincoln was sometimes compared (both favorably and in derision), Lincoln’s jokes and tales always had a moral or made a point. In political contexts, that transformed the humor into satire—sometimes stinging, sometimes subtle.

Thompson also points out that Lincoln used humor as a defense mechanism. The president constantly poked fun of himself, told self-depreciating stories, and even played to stereotype, keeping his western accent and portraying himself as a frontiersman. “[H]is consciously performed rusticity,” Thompson says, allowed Lincoln to seem genial and genuine, which made him a harder figure to attack. Critics found their own legs cut from under them because Lincoln had already stolen their saws.

“By fashioning himself as a folksy, fallible figure who lacked the prestige that caricature usually seeks to attack, Lincoln was able to use satire as a weapon without being severely wounded by it,” Thompson says.

Such defense mechanisms had their limits, though. High-running emotions and political fevers sparked by such topics as emancipation, racial equality, and military defeatism made Lincoln a target for especially vitriolic attacks. A strength of Thompson’s book is that he shows not only how Lincoln used satire, but how it was used on him—and how Lincoln responded in turn.

Thompson, an associate professor of English at Indiana University of Pennsylvania, approaches his study with a deep background in rhetorical theory. That allows him to appreciate Lincoln’s relationship to satire on a highly nuanced level, and fellow rhetoricians will easily follow along. History-oriented readers, though, might initially feel overwhelmed. For instance, Thompson talks about the distinctions satire theorists have made between “humor” and “satire” without actually defining the terms for Joker’s readers up front. Later, when he associates Lincoln with “southwestern humor,” he assumes the reader understands the conventions of the genre. Brief primers for non-rhetoricians would be useful.

Otherwise, Thompson does an excellent job navigating the multidisciplinary cross-currents he explores. Lincoln was, after all, one of the most complex individuals in the nation’s history, and Thompson is exploring one of his most sophisticated and fascinating (and largely unexplored) facets. Best of all, Thompson does so in a way that sheds light on the entire panorama of Lincoln’s times.

“That the central figure in American history was also its ultimate satirist-statesman, whose satiric discourse was also his political discourse, speaks to the heretofore unexamined prevalence and power of political satire in nineteenth-century America,” Thompson points out. His insightful look at Lincoln, then, proves to be an insightful look at America.

Chris Mackowski is the author of Grant’s Last Battle: The Story Behind the Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant (2015).