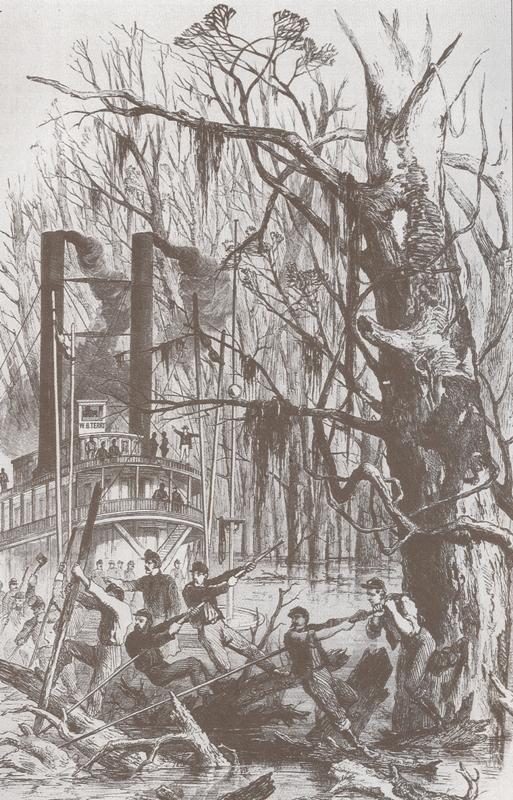

One-hundred and fifty years ago, Brigadier General John Pope faced a tactical dilemma on the Mississippi River. Confederate batteries at Island No. 10 blocked passage through a complex series of river bends. Although Pope held New Madrid, Missouri downstream from the Confederates, his troops were on the wrong side of the river. With transports and gunboats, Pope could cross the river into Tennessee and turn the Confederates out of their river fortifications. However, Flag Officer Andrew H. Foote, commander of the Mississippi River Squadron above Island No. 10, declined to risk running the Confederate position as he was still felt the sting of repulse from the February Fort Donelson expedition. Foote preferred a stand-off bombardment while waiting for an opening to exploit, but Pope was a man in a hurry and could not wait for developments.

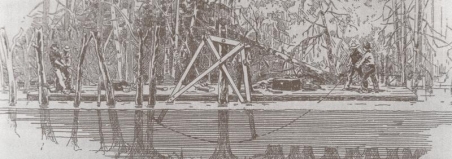

In mid-March 1862, Colonel Josiah Bissell, commanding the “Engineer Regiment of the West,” surveyed the land north and east of New Madrid. Reporting to Pope, Bissell found swamps and bottom-land inundated with the early spring flood waters. Bissell suggested a canal to provide passage for steamboats. Bissell’s plan called for a path through some 12 miles of swamp, using some of the natural bayous and soughs, cut 50 feet wide and 4 ½ feet deep. The chosen course followed Wilson’s Bayou into the swamps, then cut across to join St. John’s Bayou—north of New Madrid. The mouth of St. John’s provided a save cove to hide the transports from Confederate observers. Instead of facing an enemy force, Bissell’s engineers would fight the barriers set in place by the Mississippi River.

For nineteen days Bissell’s men worked to clear the passage. Where open bayou allowed, the engineers used a submerged saw to clear the trees (pictured above). In other cases, the only practical method to clear the way was by hand. In his official report, Pope described the work as, “prosecuted with untiring energy and determination, under exposures and privations very unusual even in the history of warfare.” When completed on April 4th, the canal, or more accurately a channel, allowed passage of four steamboats and several barges—but no gunboats. Foote finally agreed to allow Commander Henry Walke to run the USS Carondelet past the Confederate batteries on the night of April 4th. A few nights later the USS Pittsburgh made the same run. Now with two gunboats and transports, Pope directed a crossing to the Tennessee side of the river. While the two gunboats cleared Confederate defenders downstream from New Madrid, on April 7th Federal troops landed at Tiptonville, Tennessee. This move isolated Island No. 10 and forced the surrender of the Confederate command. Bissell’s canal through the swamp was a critical element to Pope’s success at Island No. 10.

A visitor to the battlefield of Island No. 10 today will see a landscape vastly different than that of 1862. The site of the canal is not easy to find. In the decades after the Civil War, flood control measures and bottom land reclamation projects turned swamps into farmlands. As result, the swamps around Wilson’s Bayou became little more than a strip of trees.

A great deal of imagination is required to visualize steamboats working through what was once a swamp.

More changes came after 1927. The Birds Point-New Madrid Floodway system completed the alteration of the landscape. The bottom land of St. Johns Bayou became the lower end of a massive floodway system. Engineers designed the system to handle over a half million cubic feet per second of floodwaters, but altered part of the meandering bayou into a long, straight ditch.

The campaign to capture Island No. 10 was the second major surrender of Confederate forces in the west in 1862. The number of captured Confederates probably numbered 4,500—rather than the 7,000 claimed by Pope. The victory came with relatively little bloodshed, particularly compared to battles which would later follow. Combined, both sides reported just over 100 killed, wounded, or missing. The low casualty figures allude to a different sort of contest along the Mississippi; men on both sides fought against the stubborn river itself. Engineers worked to clear passages for ships and shore up levees to protect defenses. Snags might damage a vessel more than enemy gunfire. And the rise and fall of the river dictated the pace of operations.

Even though the combatants of 1862 have long since laid down their weapons, the contest between man and the river remains. The land around New Madrid is still a battleground of sorts in that contest, as witnessed just last year with the spring floods.

Craig Swain is a consultant from Virginia but is a native Missourian. His background includes a degree in history and service in the Army. Craig’s focus is the study of Civil War Artillery, which you can read about on his blog—To the Sound of the Guns.

Image credits: Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Magazine, April 19, 1862; Battles and Leaders, Volume 1, p 460; and the author’s personal collection.