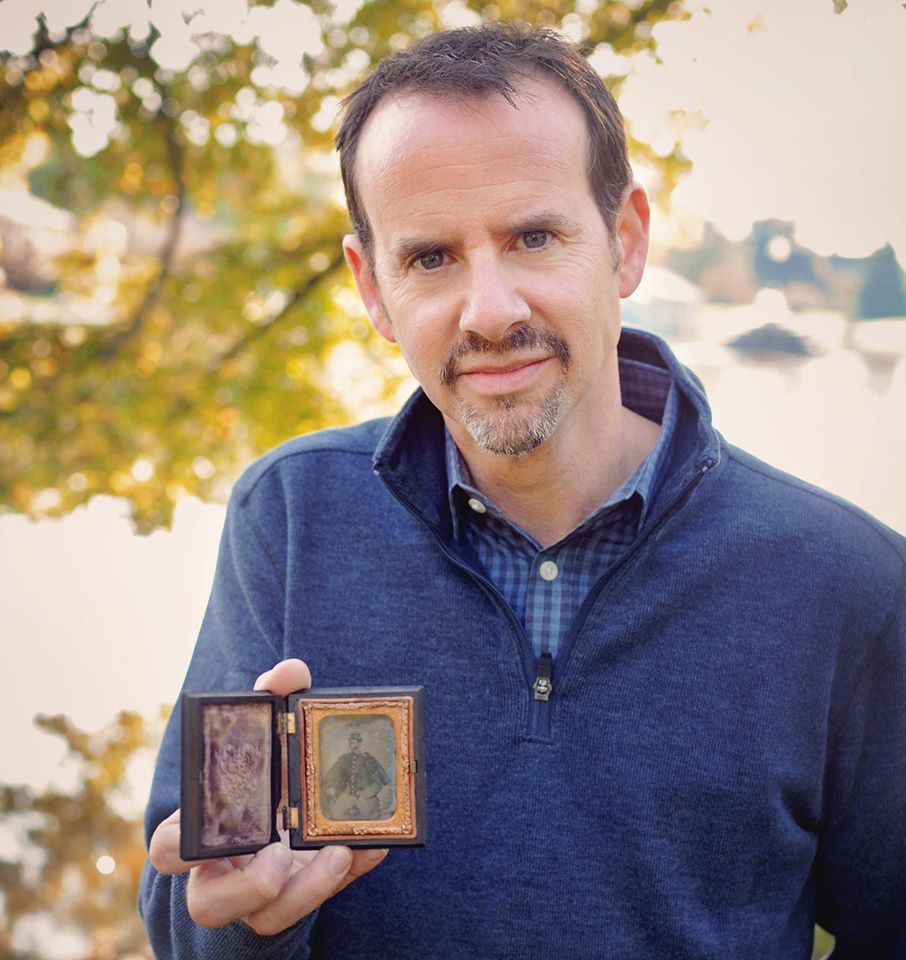

Garry Adelman holds the first Civil War image he ever owned, an ambrotype of an unidentified Union soldier given to him by his grandmother at age 16.

It was June 1983, the last day of Garry Adelman’s sophomore year in high school. Finished with exams and waiting for a friend, he headed, somewhat randomly, for the school library. Adelman wasn’t the kind of kid who sank time into bookshelf browsing, and to this day he has no idea what compelled him toward the stacks. But he was there, and the books were there, and a white one with blood-red letters down its spine caught his eye. He plucked it from the shelf, and in that instant changed his life.

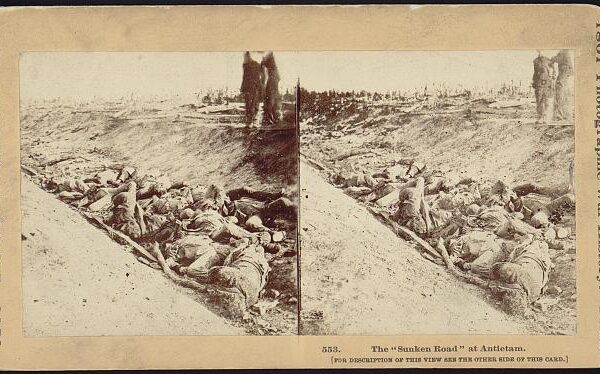

The book was William A. Frassanito’s Antietam: The Photographic Legacy of America’s Bloodiest Day. In it were dozens of period photographs of the battlefield, paired with modern shots taken at the same angles—a sort of “then and now” comparison spanning a century. Adelman opened the book to then-and-now photos of Dunker Church, a modest house of worship that had been a focal point of Union attacks. In the first photo, the church’s whitewashed walls are riddled with shell holes. In the modern view, the holes are gone and the trees have thinned. A monument stands on a small rise once crowded with dead Confederates.

Adelman was a D student in history, barely interested in the subject. But photographs were a different story. Their ability to “capture the passage of time over place,” as he puts it, had intrigued him for as long as he could remember. He liked photographing buildings marked for demolition, with the idea of taking “after” photos later. Whenever he saw shots of his younger self, he wondered where they’d been taken and what those places looked like now. Adelman was a then-and-now enthusiast almost by nature. But he had no idea that it was a historical genre in its own right, or that photography even existed that long ago. Standing in the library, flipping through Frassanito’s book, he felt a jolt of excitement. Says Adelman: “I became, at that moment, obsessed with the Civil War and Civil War photography.”

Soon the Illinois teenager was devouring Civil War books, memorizing every detail of a war he’d blown off in class. He studied 19th-century photographic techniques, and buried himself in Frassanito’s work. Still, when he headed to college at Michigan State, it wasn’t for a history degree. “I was that rare kid who knew exactly what I was going to do with my life even before high school,” Adelman explains. He wanted to run restaurants, maybe even own them. So he majored in hotel and restaurant management. In 1989, he moved to Chicago to work for the improbably named Lettuce Entertain You Enterprises, managing a trendy restaurant called Hat Dance (“an upscale Mexican place with a Japanese twist,” as Adelman describes it). The hours were brutal, but he was good at his job and moving up fast. His fate should have been sealed.

Except that by this point his Civil War hobby had become more like an insatiability. Adelman had taken his first trip to the Gettysburg battlefield in college, and now he couldn’t stay away. “I would close up [the restaurant] on Saturday night at 2 a.m., hop in the car, drive 12 hours to Gettysburg, spend that afternoon and the next day there, and then drive back,” he recalls. He used his scant time off for nothing else, his knowledge of the battle growing encyclopedic. Back home, Adelman’s friends and coworkers didn’t share his passion, but he compulsively overwhelmed them with it anyway. “I singlehandedly made them hate the Civil War and in some cases American history because of how hard I would push it,” Adelman admits.

But during his Gettysburg trips, Adelman started encountering people equally obsessed. On one trip, while browsing a relics shop, he met Tim Smith, a soon-to-be Gettysburg licensed battlefield guide whose staggering Civil War knowledge made Adelman feel like a kindergartner. They struck an instant friendship. Whenever Adelman was in town, he would crash at Smith’s house, and the two would (and still do) spend endless time tromping the battlefield together.

Adelman also made contact with William Frassanito. Many Civil War photographs have never been matched to an exact location, and Adelman had joined the ranks of those who scour battlefields in search of these hallowed spots. Early on, he identified the place where Alexander Gardner took his famous “All Over Now” photograph of a dead Confederate soldier arched backward in a pile of boulders. “I just had a different theory, that maybe it was on an offshoot of a stream that only becomes a stream during heavy rains like they had after the battle,” says Adelman. The photo was listed in one of Frassanito’s books as unlocated, so Adelman called him. A teenager had stumbled upon the site two years earlier, the author revealed. But Adelman didn’t care. For one, he was on the phone with Bill Frassanito. And he had made his first attempt to contribute to history rather than only consume it.

His transformation from hobbyist to historian accelerated from there. In 1992, Adelman turned down a chance to run his own Chicago restaurant and moved to Gettysburg instead. He opened a coffeehouse, eventually selling the business to Gettysburg College, then ran the school’s food service operations for a few years. In the meantime, he passed the grueling test to become a Gettysburg licensed battlefield guide and, like Tim Smith, started leading tourists around the national park. In 1997, he and Smith published a book on Devil’s Den that won the prestigious Bachelder-Coddington Award. Adelman has since written or edited 19 more Civil War books, including then-and-now books on Antietam and the Manassas battlefields.

In 1999 Adelman cut all ties to the food business, at last propelling himself into history full time. He took a job as director of marketing at Thomas Publications—the company that put out Frassanito’s books—and helped found the Center for Civil War Photography, a small nonprofit aimed at enhancing public access to wartime images; Adelman still serves as its vice president. In 2002, after earning a master’s in applied history at Shippensburg University, he joined the historical consulting firm History Associates Inc., where he helped develop a line of business called interpretive planning. One of his major clients was the Civil War Trust, which purchases and preserves Civil War land. Adelman started interpreting battlefields and giving tours to donors, happily figuring he had just reached the pinnacle of his career.

He hadn’t. In 2010, the Civil War Trust offered him a job as director of history and education. “It’s beyond any dream job that I ever could have conceived,” Adelman says. The former restaurant manager now spends his days developing animated maps, battlefield apps, and brief videos about basic Civil War topics that are viewed by hundreds of thousands of people. He also oversees the stewardship of the 8,000 acres of battlefields that the Civil War Trust owns, and helps raise funds to support the organization’s mission. “Everything I do at work goes toward permanently preserving Civil War land and getting people excited about history and the Civil War,” says Adelman, who is now 48 years old. “It’s the perfect job.”

But the insatiability that got him to this place still compels him to do more—particularly for the future of Civil War photography. New Civil War photos emerge all the time, he explains. So do new details about known ones. For Adelman, hunting for these details has become its own quest. A few years ago, when the Library of Congress made extremely high-resolution versions of its collection of wartime photos available to the public, Adelman started zooming into them to reveal elements and features that someone looking at the larger photo would miss: the buttons and belt buckles on uniforms; the soldier cradling a stray dog; the Antietam grave digger, arm resting on a rifle stack, who is staring right at you. The practice has almost a time-travel effect, so clear are the details. “It really helps take people back to the moment of exposure,” Adelman says. The Facebook page on which he shares these images (“Garry Adelman’s Civil War Page”) has more than 9,000 followers.

Meanwhile, Adelman continues to search battlefields for the exact sites where dozens of still-unlocated Civil War photos were taken. He has found many. But a few—including “A Harvest of Death,” a series of haunting photos of dead soldiers, taken somewhere on the Gettysburg battlefield—have eluded him for nearly three decades. “The whole purpose is that you transform a photograph from an illustration in a book to a primary document,” he explains. “Once you know when and where it was taken, suddenly the information in that photo can teach you sometimes as much or more as any other account. You know exactly what that stone wall looked like. You know just which trees were here and what the terrain looked like. And there is no other account, no map, nothing else that can do that as precisely as a photo taken right after the battle.”

A few years ago, Adelman came into possession of the same copy of Antietam he had pulled from the library bookshelf back in 1983. The due-date card is still inside, stamped with the date he first borrowed it. “That book started my whole life, you could say,” Adelman reasons. Without it, he never would have moved east, met his wife, or had his two boys. He never would have known what it feels like to pursue a passion that has proved so enduring. “I thought my interest in the Civil War would eventually wane or wear out, but I’m more into it today than I’ve ever been,” he says. “I’m pretty well convinced, like the expansion of the universe, it will remain constant forever.”

Jenny Johnston is a freelance writer and editor based in San Francisco.

Jenny Johnston is a freelance writer and editor based in San Francisco.

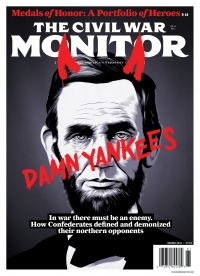

This article appeared in the Spring 2016 issue of The Civil War Monitor. Interested in purchasing a copy? Click here.

This article appeared in the Spring 2016 issue of The Civil War Monitor. Interested in purchasing a copy? Click here.