Today marks the sesquicentennial of the fall of New Orleans (April 25, 1862). As such, The Civil War Monitor is commemorating this event with a two-part series on the surrender. Below is Part One which focuses on the men and the skirmishes behind New Orleans’ surrender.

From the beginning of the war and Winfield Scott’s Anaconda Plan, the Yankees entertained notions of seizing control of the Mississippi River and thereby dividing the Confederacy in two. To successfully achieve this goal, the Union Navy first needed to enter the mouth of the river, capture New Orleans, and close off this vital entrance to Rebel ships. As such, on January 20th, Union Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles ordered Flag-Officer David G. Farragut to:

collect such vessels as can be spared from the blockade and proceed up the Mississippi River and reduce the defenses which guard the approaches to New Orleans, when you will appear off that city and take possession of it under the guns of your squadron, and hoist the American flag thereon.1

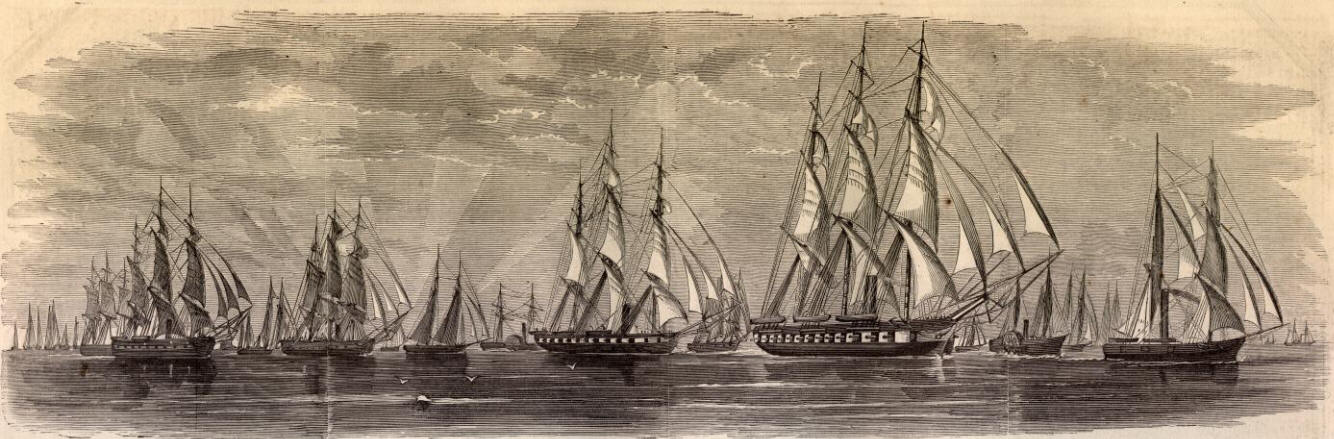

In January of 1862, Union Flag-Officer David G. Farragut and his West Gulf Blockading Squadron began this mission. By April, the way to New Orleans was soon open save for Fort Jackson and Fort St. Philip—above the Head of the Passes—which sit approximately 70 miles below the city.

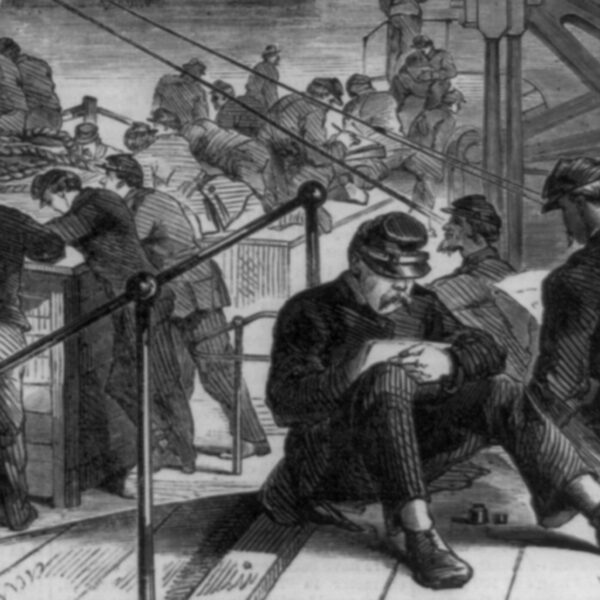

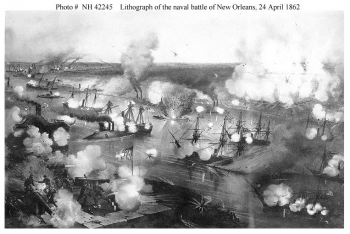

Besides the forts’ armaments, the Federal fleet also faced various obstructions that the Confederates placed in the river, as well as a handful of Southern ships, including two ironclads: the CSS Manassas and the CSS Louisiana. To better plan the attack on New Orleans, Farragut based his operations from Ship Island, Mississippi, assembling Commander David D. Porter’s fleet of mortar schooners and 24 other vessels. Operations began in earnest on April 16th and continued for a week as the mortar schooners bombarded Forts Jackson and St. Philip. As the shells continued to rain down, sailors from USS Itasca and USS Pinola opened a gap in the riverine obstructions.

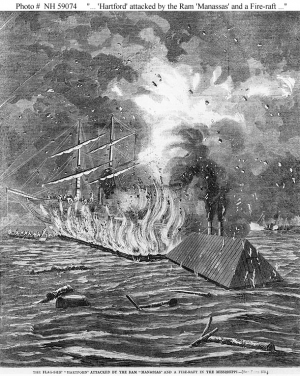

On the morning of April 24th, Farragut ordered the West Gulf Blockading Squadron to pass the forts and head for New Orleans. At 2am, the Union fleet began moving upstream. Within 75 minutes, they endured fire from the Confederate forts. The first division cleared the forts successfully but the second division “had a rough time of it.”2 As Farragut’s flagship, the USS Hartford, cleared the two forts, it suddenly had to turn to avoid  a Confederate fire raft. In the process it to run aground. Seeing the Union ship in trouble, the Confederates redirected their attention towards the Hartford, thereby causing a fire to break out. Moving quickly, the Union sailors extinguished the flames and set the ship back on its course. Farragut himself reported that,

a Confederate fire raft. In the process it to run aground. Seeing the Union ship in trouble, the Confederates redirected their attention towards the Hartford, thereby causing a fire to break out. Moving quickly, the Union sailors extinguished the flames and set the ship back on its course. Farragut himself reported that,

The ram pushed a fireraft on me. In trying to avoid it I ran the ship on shore and he then pushed the fire raft on to

me and got the ship on fire all along one side. I thought it was all up with us, but we put it out and got again and proceeded up the river fighting our

way. We have destroyed all but two of the gunboats, and those will have to surrender with the forts. I intend to follow up my success and push for New Orleans.3

Once above the forts, the Union ships encountered the Rebel’s River Defense Fleet and the CSS Manassas. The Manassas made a failed attempt to ram the USS Pensacola and then headed downstream to strike the USS Brooklyn. In the process, the Confederate fort accidentally fired upon their own ironclad, but it easily endured the bombardment. The Manassas then rammed the Brooklyn, hitting its coal bunkers. The Manassas headed further downstream before her captain ran her aground. Union gun fire soon destroyed the ironclad. Thus, the Rebels had failed in their attempt to stop the Union mission.

Having successfully cleared the forts with minimal losses, Farragut’s fleet headed upstream to New Orleans. Once Major General Mansfield Lovell, the Confederate commander, realized that the Union Navy had broken through his defenses, there was only one option left: evacuation. Lovell loaded his troops and supplies aboard the railroad and sent it 78 miles north to Camp Moore. Lovell then sent a final message to Richmond, “The enemy has passed our forts. It is too late to send any guns here; they had better go to Vicksburg.”4 The unfinished CSS Mississippi was hastily launched but as no towboat could take her to Memphis, the Rebels destroyed her. Likewise, the Confederates burned all military stores, ships, warehouses, and anything considered useful to the Union. Meanwhile, panic-stricken citizens broke into stores, burned cotton and other supplies, and destroyed much of the waterfront.

Having successfully cleared the forts with minimal losses, Farragut’s fleet headed upstream to New Orleans. Once Major General Mansfield Lovell, the Confederate commander, realized that the Union Navy had broken through his defenses, there was only one option left: evacuation. Lovell loaded his troops and supplies aboard the railroad and sent it 78 miles north to Camp Moore. Lovell then sent a final message to Richmond, “The enemy has passed our forts. It is too late to send any guns here; they had better go to Vicksburg.”4 The unfinished CSS Mississippi was hastily launched but as no towboat could take her to Memphis, the Rebels destroyed her. Likewise, the Confederates burned all military stores, ships, warehouses, and anything considered useful to the Union. Meanwhile, panic-stricken citizens broke into stores, burned cotton and other supplies, and destroyed much of the waterfront.

At 2 pm on April 25th, Farragut formally accepted the surrender of New Orleans despite the fact that General Lovell refused to admit defeat. Farragut sent Captain Bailey, First Division Commander from the USS Cayuga, to accept the surrender. There he met a defiant armed mob and witnessed William B. Mumford pulling down a Union flag previously raised by sailors of the USS Pensacola. While Farragut did not retaliate and destroy the city, he did return on April 29th with 250 marines from the USS Hartford to remove the Louisiana State flag from the City Hall and restore order.

Such retaliatory efforts on the part of the Southerners did not mar the Union victory. A few days later, Navy Captain Theodorus Bailey proudly reported that,

In the face of casemated forts, fire rafts, ironclad steam rams, and a fleet of gunboats, we have the swept the Mississippi of its defenses as far as Baton Rouge and perhaps Memphis. The United States flag waves over Forts Jackson, St. Philip, Livingston, and Pike, and also the city of New Orleans. We fought two great battles; that of the passage of the forts and encounter with the ironclads and gunboats has not been surpassed in naval history. We have done all this with wooden ships and gunboats.5

Once the Union Navy surrounded and isolated New Orleans, the conquest of Forts Jackson and St. Philip was easy. The two garrisons surrendered on April 28th.

In sum, the New Orleans campaign amassed an estimated 1,011 casualties. And while the fall of the city was anti-climactic, the Southern port soon found itself occupied by Federal forces—most notably Benjamin Butler. The capture of New Orleans was a huge coup for the Union War effort; David Porter later recalled that,

the most important event of the War of the Rebellion, with the exception of the fall of Richmond, was the capture of New Orleans and the forts Jackson and St. Philip, guarding the approach to that city.6

Want to learn more about the Fall of New Orleans? Check Out Part 2 over on The Civil War Navy Sesquicentennial Blog.

Image Credit: Harper’s Weekly, May 10, 1862; The U.S. Historical Center Online Library of Images.

Citations:

1. Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, Series 1, Volume 18, p. 7.

2. ORN, Series 1, Volume 18, p. 142.

3. ORN, Series 1, Volume 18, p. 142.

4. ORN, Series 1, Volume 18, p. 330.

3. ORN, Series 1, Volume 18, p. 149.

5. Battles & Leaders of the Civil War, Volume 2, p. 22.