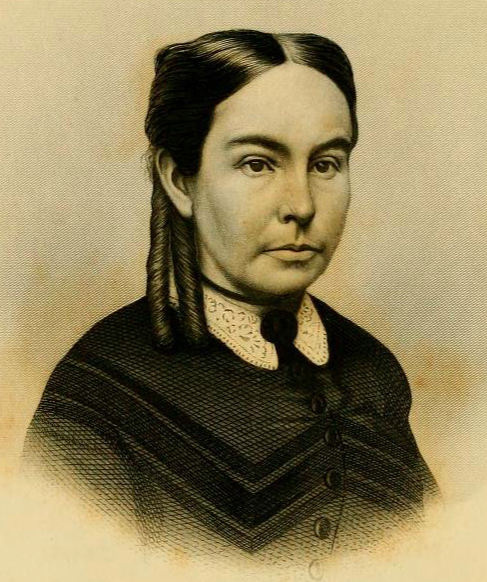

Julia Wheelock

One hundred fifty-five years ago this month, 28-year-old Michigan resident Julia Wheelcock learned that her brother, Orville, a soldier in the 8th Michigan Infantry, had been wounded at the September 1, 1862, Battle of Chantilly. She and Orville’s wife, Anna, along with Anna’s sister, Mrs. Peck, determined to travel to Virginia to look for him in the hospitals of Alexandria. The following is an account of their initial days in Alexandria as recorded by Julia in her diary, which was published in 1870 under the title The Boys in White.

Soon the ancient city of Alexandria—ancient in American history—heaves in sight. It presents a gloomy, dingy, dilapidated appearance. As we set foot upon the “sacred soil,” we experience quickened heart-beatings, for we know that this terrible suspense will soon give place to, it may be, a dreadful reality. As we pass up King street we pause a moment to look at the building where the brave young Ellsworth fell, drop a tear to his memory, and hasten on. Turning from King into Washington street, we notice a soldier in full uniform with a shouldered musket, pacing to and fro in front of what appeared to be a church. We are told by the guard that it is the Southern M. E. Church, but now used for a hospital. We enter the building, make known the object of our visit, but find he is not there. My poor sister could go no farther; she seemed to have a presentiment that her worst fears were about to be realized. “Oh!” she says, “his wound is fatal, for he came to me in my dreams only a few nights since, looking worn and pale and haggard, having lost a limb in battle, and seemed to say, ‘My work is done, I’m weary and must rest.’” She felt that his work was done, and if so, well done, having “fought the good fight and kept the faith,” and that he had gone to receive the crown.

And yet, amid these consoling reflections, thoughts of her own desolation and the great loss she would sustain if her fears were realized, would rush upon her with an overwhelming force, crushing out life’s bright hopes, while the language of her heart was, “Who will care for the fatherless now?” — forgetting for the time the promise of God, “Leave thy fatherless children with me and I will preserve them alive.” We tried to comfort her, saying we should soon have him with us; that one so strong, physically, would certainly survive the amputation of a limb; and, bidding her be of good cheer, Mrs. Peck and I hastened to the next hospital—the Lyceum Hall—but to our anxious inquiry met with the same reply as before. We cross the street to the Baptist church, which is also used for a hospital, our fears every moment increasing. Happening to look back before entering this hospital, to the one we had just left, we saw some one beckoning to us to return. Hope began to revive; we hurried back and were told he was there, and doing well, though still very weak. Our informant asked us if we would see him? “No,” we replied, “not until we have informed his wife,” requesting him in the mean-time to try and prepare his mind to see her, cautioning him to break the news very carefully, fearing that the excitement might prove injurious to one so weak. Having given these instructions, I left Mrs. P., and hurried back with a light heart and a quick step to the hospital where my sister was waiting in such agony of suspense. She heard my voice before reaching the hospital, exclaiming at almost every step: “I’ve found him! I’ve found him! Oh, Anna, come quickly!” I did not realize that I was in the streets of a city, attracting the notice of passers-by, nor did I much care, for a deep anxiety and long days of suspense had given place to joyful hopes and sweet anticipations.

A wartime view of Alexandria, Virginia

She rose to accompany me, hesitated a moment, and then sank back upon her seat, and with a look almost of despair, says: “Julia, are you sure, have you seen him?” I assured her, that though I had not seen him, there could be no mistake, for they certainly would not have said he was there, had he not been. Thus reassured she rose the second time, took my arm, and we started. We had gone but a few steps when our ears were saluted with the sad and mournful tones of the fife and muffled drum, and on looking back we saw a soldier’s funeral procession approaching—a scene I had never before witnessed, but one with which I was destined to become familiar. How unlike a funeral at home! No train of weeping friends follow his bier; yet one of our country’s heroes, one of the “boys in white,” lies in that plain coffin. He is escorted to his final resting-place by perhaps a dozen comrades, who go with unfixed bayonets, and arms reversed, keeping time with their slow tread to the solemn notes of the “Dead March,” plaintively executed by some of their number….

The tear of sympathy unbidden starts at the sight of the “unknown,” and for the bereaved friends who weep in far off homes. In a few minutes we are at the Lyceum Hospital where, instead of the realization of our hopes, heart-rending tidings await us. He who, but a few moments before, was the bearer of such good news, again makes his appearance; but why is his countenance so sad? His own words will tell. “I was mistaken, he is not here;” but something either in his tone or manner indicated that he had been there, and at the same moment we all inquired: “Oh, where is he?” “He is dead!” was the reply. Oh, that terrible word—”dead!” How suddenly it blighted our fond hopes, and turned our anticipated joy into the deepest grief.

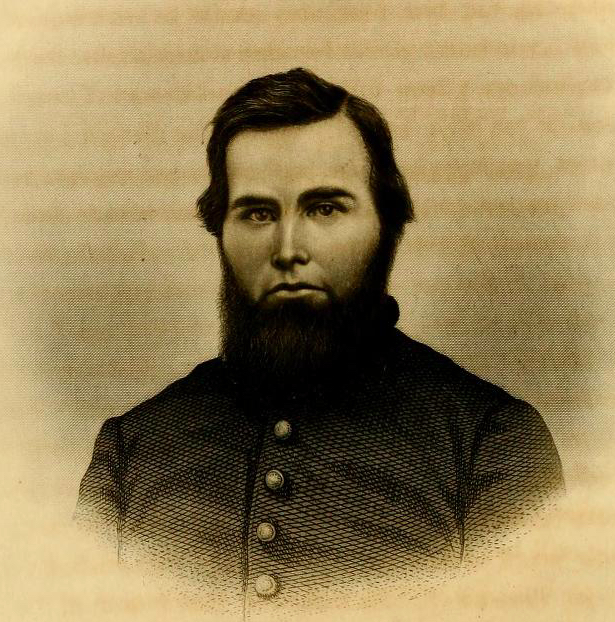

From the hospital we were conducted to the Rev. Mr. Reid’s, my poor sister being carried in an almost senseless condition, where we spent a sleepless night brooding over our sorrow and shedding the unavailing tear. Oh! that never-to-be-forgotten day! A day not only of bright, but blighted hopes, a day of mourning, of sadness and bereavement, a day that revealed to an anxious wife that she was a widow and her children fatherless; a day that said to my sad heart, “Thy brother has fallen.” He died like thousands of others, far from home and friends, with no loved kindred near. But God had sent an angel of mercy in human form—that noble girl, Miss Clara F. Jones, of Philadelphia—to watch over and administer to his wants. She watched him day by day as he grew weaker, she stood beside him in his dying moments, held his icy hand in hers, wiped the death dew from his brow, received his last message for his wife and child, and, when life had fled, prepared him as far as she could for his burial. Such are her daily duties. May God reward her with the rich blessing of his love….

The morning of the 15th, sister Anna and I, accompanied by Rev. Mr. Reid and wife, Miss Jones and Chaplain Gage, visited brother’s grave. Oh! how could we realize, as we stood by that little, narrow, turfless mound, that dear Orville lay there? His poor heart-broken widow threw herself upon his grave and gave vent to her deep grief in sobs and bitter tears. Nearly three hundred brave “boys in white” lay side by side in the same enclosure, with not even a stone to mark the place where they were sleeping, nor a spear of grass growing upon their graves, simply buried out of sight; but each little mound is cherished, oh, how sacredly by some one!…

Orville Wheelock

To-day we visited the Lyceum Hospital, where so recently dear Orville took his leave of earth. Only a few days ago he was among the sufferers there; now he is forever at rest. The hospital is full of the wounded from the late battles, suffering, oh, so much, and yet so patiently! There are many others upon whom Death has already set his seal, and whose places will soon be vacant, or occupied by others. Oh, how I long to stay and go to work for them! Perhaps I might be the means of saving somebody’s husband or brother….

Sept. 17th

This morning we took leave of our kind host and lady, the dear Miss Jones, and other friends, and, with one long, lingering look at that hospital, around which, to us, a sacred solemnity still lingers, hastened to the wharf and took the first boat to Washington. We had scarcely landed, when a fine-looking officer approached us, and extended his hand to my sister, inquiring at the same time, “Did you find your husband?” She could make no reply; there was no need of words, he understood it all. We soon recognized the countenance of Lieutenant Stevenson, of the Second Michigan Volunteers, with whom we fell in company on our way to Washington. In a moment he is gone, and we see him no more; but the earnest solicitude of the stranger to know whether our fond hopes were realized, and his kind sympathy in our affliction, will long be cherished as one of the pleasant remembrances of this sad journey. And we will pray God to watch over and protect him and return him in safety to his dear family. But should he fall amid the din of battle, or become a victim to disease, may kind hands administer to his wants, and loving, sympathizing friends comfort the bereaved widow and orphans….

My mind is at length made up to remain, and engage in the work of caring for the sick and wounded, as my desire to do so has increased with every day and almost every hour since our arrival….

Sept. 18th

Sister Anna and Mrs. Peck started for Michigan this morning. One week ago to-day, we left home for this city. Oh! what bitter experiences, what anxious fears, what terrible suspense, what dreadful realities have been ours in this one short week! As I bade my sister “good-by” at the cars, she exclaimed, “Oh, Julia! How can I return to my children without their father? Their injunction, ‘Be sure and bring papa home with you,’ still rings in my ears.” My heart was too heavily burdened to reply; the train moved on; I retraced my steps, and have spent the remainder of the day in my room lonely and sad, reflecting upon the past and trying to penetrate the future.

A few days after my sister’s arrival home, instead of joy and gladness, the friends meet with bowed heads and stricken hearts to observe the solemn services of a soldier’s funeral. Rev. Isaac Errett officiated. His sermon being extemporaneous, not even a synopsis of it was preserved….

Julia Wheelcock would remain in Virginia and join the Michigan Relief Association, a group whose purpose was to provide care for Michigan troops. She remained active for the remainder of the war, even travelling to various battlefields to help nurse the wounded. She lived in Washington, D.C., until 1873, when she married a Michigan man and returned with him to their home state. They had two sons. Julia died in 1900 at the age of 66.