Historian George C. Rable

Few scholars have produced as many groundbreaking works as Civil War historian George C. Rable. Since his retirement from teaching in 2016, a group of his former doctoral students have worked on a festschrift to honor their mentor, culminating now with the release of American Discord; The Republic and Its People in the Civil War Era (LSU Press, 2020). Here, two of his former protégés trace Rable’s illustrious career, highlighting the significance of his works while uncovering the research and writing method that has earned him an unprecedented number of awards and accolades.

“I don’t have a thesis,” George Rable responded when asked about his then-current book project during a 1998 job interview at the University of Alabama, providing a glimpse into his research and writing method that had already produced two highly influential works. Intrigued by his unorthodox answer, the committee eagerly offered the esteemed historian their Charles Summersell Chair of Southern History. Rable accepted, and during his 18 years in the position added three more widely praised books to his impressive vita while shepherding through over 20 doctoral students.[1] Moreover, the book he was working on when hired—Fredericksburg! Fredericksburg!—eventually garnered a triple crown of awards: the Jefferson Davis Award, the Douglas Southall Freeman Award, and perhaps the highest award in the Civil War history field, the Lincoln Prize.

While historians have uncovered well-supported theses from his works, Rable insists his best books are without thesis. Indeed, the renowned scholar labels his “most thesis-driven book,” The Confederate Republic, his least successful effort. Unraveling this apparent paradox requires a story of its own, tracing Rable’s scholarly path and a method that has made him a widely acknowledged master craftsman of narrative history.

In the fall of 1968 George C. Rable entered Bluffton University, a Mennonite institution in Ohio, expecting to emerge four years later prepared to teach high school math. However, he fell under the spell of an inspiring yet demanding history professor named John D. Unruh (a future Pulitzer Prize finalist and winner of seven academic book awards), taking every course the captivating instructor taught. Unruh was likewise impressed with the energetic and devoted undergraduate, eventually encouraging Rable to pursue an advanced history degree.

With Unruh’s recommendation, Rable enrolled in graduate school at Louisiana State University. It was a good fit; Rable wanted to study Reconstruction (his senior thesis was on Andrew Johnson’s impeachment) and LSU’s Pulitzer Prize-winning historian T. Harry Williams had an interest in political and Reconstruction history. The soon-to-be acclaimed scholar William J. Cooper was also on staff, using what Rable recalls as “tough love” to hone his students’ writing. After six years under their tutelage, Rable defended his massive 764-page dissertation. While most newly-minted PhDs usually have to expand their dissertations to attract publishers, Rable faced the task of reduction.

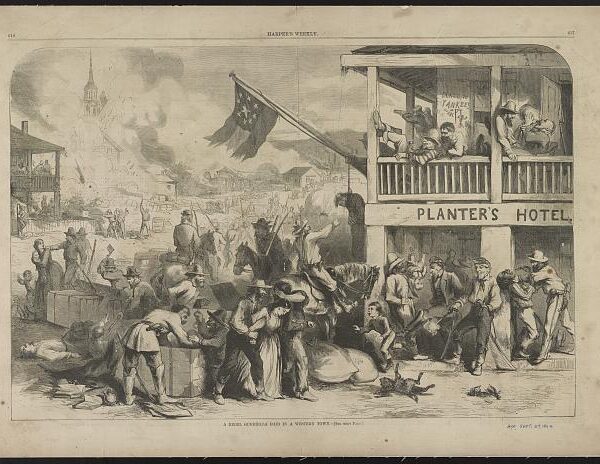

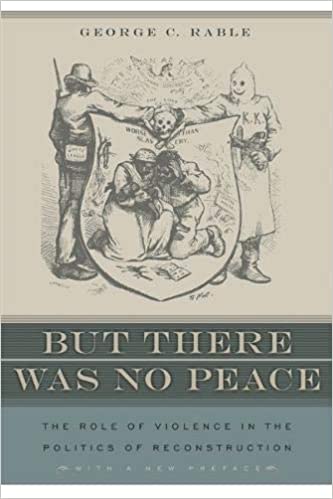

In 1984, University of Georgia Press published a slimmed-down version as But There Was No Peace: The Role of Violence in the Politics of Reconstruction. Tracing events from the 1866 New Orleans riot through redemption, Rable chronicled how armed Democrats secured through terror what they could not by votes: white supremacy and the destruction of the Republican Party in the South. Rable characterized the former Confederates’ campaign of violence, which included murder, torture, and rape, as “a counterrevolutionary tide” overthrowing what they deemed the “revolutionary” postwar Republican governments. “Terrorism in the Reconstruction era was instrumental in achieving the ends desired by its perpetrators,” Rable argued. Reconstruction historians who “overemphasized the weaknesses of northern policy and ideology in explaining the failure of Reconstruction,” were ignoring “the persistence and strength of [violent] southern resistance.”

These assertions drew scholarly attention as they contrasted with the then-current apologias that focused on Reconstruction’s successes, or that blamed its failures on disagreements within the Republican Party and/or President Grant’s indifference. James McPherson, for example, noted that while studies of political policy all assume that laws have weight, Rable demonstrated their limits.[2] Rable’s emphasis on the role of white southern violence in derailing Reconstruction shifted and shaped much of the subsequent scholarly work on the era and the Klan. It was quite an accomplishment for a first-time author.

But There Was No Peace, as well as six subsequent published articles (one of which helped dismantle C. Vann Woodward’s revisionist interpretation of the Compromise of 1877), established Rable as a Reconstruction historian.[3] “I sort of looked down my nose at Civil War [historians],” he admits, “particularly military people.” Fittingly, his next work started out as an examination of women during Reconstruction based on letters he had already gathered. He soon discovered there was not enough material, however, and this ironically took him backward to the Civil War.

Nevertheless, he used the same approach—a broad look at the experiences of everyday people during stressful times—in his second book, Civil Wars: Women and the Crisis of Southern Nationalism (1989). The original manuscript covered the antebellum years through Reconstruction; but because his richest research material related to the Civil War, Anne Firor Scott (who all but established the field of southern women’s history) encouraged Rable to focus on the war. His exhaustive research revealed white southern women turning against and undermining the conflict as they faced inflation, invasion, loss of property, and death. Yet thrown to their own resources, women also helped sustain the Confederacy by taking on roles formerly reserved exclusively for white men, such as running plantations and working as clerks. Some even shouldered rifles in home guard units. Rable’s book is still a good starting point for a general overview of the challenges southern women of all classes confronted during the conflict.

Further, Civil Wars challenged standard interpretation established by the same scholar who had encouraged Rable to focus on the war. Where Scott had influentially argued that the Civil War was a watershed later sparking elite southern women’s activism during the Progressive era, Rable’s broader focus on women of all classes reached significantly different conclusions. The end of fighting did little to improve the lot of yeomen and poor urban women who lacked the material resources to shield themselves during the conflict. Their problems shifted, and in some cases worsened, as they negotiated and often competed with the formerly enslaved population for education and jobs. While many women entered fields that had once provided autonomy (such as teaching), they quickly discovered that lower salaries and more scrutiny blocked their road to independence. These and other factors challenged Scott’s influential thesis, as Rable insisted that while the war had turned everything around, most southern women’s lives and statuses eventually returned to where they had been, yet with less hope for lasting change.

It was this “change without change,” as Rable labeled it, which drew scholarly attention. Joan Cashin argued that Rable’s evidence might better support the conclusion that the war created disruptions in women’s gender roles and statuses, rather than having caused changes that quickly reverted to old patterns. On the other hand, Elizabeth Fox-Genovese praised Rable for “demonstrating the ways in which the upheavals of war can dislocate women from traditional patterns without fundamentally altering their basic values.” This subtle disagreement foretold the book’s historiographical significance. In challenging Scott, Civil Wars framed questions that historians asked following the groundbreaking work, shaping debates still raging in graduate seminars and influencing subsequent publications. As such, Civil Wars is a foundational work in the field of Civil War gender studies.

Cashin and Fox-Genovese agreed on the impressiveness of Rable’s extensive research, with his list of manuscript sources containing approximately 300 different collections at over 20 institutional repositories. Cashin noted Rable’s “impressive variety of sources, including manuscript collections from every Confederate state, memoirs, newspapers, and public records.” Fox-Genovese asserted that his extensive research created “the most comprehensive modern account of white southern women’s experience of the Civil War.”[4]

The pathbreaking Civil Wars earned Rable the 1991 Julia Cherry Spruill Prize, presented to the best book in southern women’s history, and his first Jefferson Davis Award, given for the outstanding narrative on the Confederacy and the American Civil War. These awards established Rable’s reputation for thoroughness, which would only grow as prodigious research and narrative history became hallmarks of his works.

By examining the accounts of everyday people, Civil Wars extended the approach Rable had taken with But There Was No Peace. This was bottom-up history, drawn from personal diaries, memoirs, letters, and other writings of the often-disregarded masses. While reviewers noted historiographically important interpretations in each of the works, Rable’s focus was more on deeply researching the struggles of those navigating difficult times and then narrating their experiences with readable and engaging prose.

Yet instead of continuing this successful formula of extensive “bottom up” research to extract revelatory and enlightening narratives, Rable’s next book took a different approach, as he considers The Confederate Republic: A Revolution Against Politics (1994) his “only thesis-driven book.” The Confederacy’s founders, Rable argued, believed their success hinged on linking slavery’s protection with the protection of personal freedoms, thereby ensuring unity between slaveholders and non-slaveholders. Slavery and liberty were both protected in the Confederate Constitution; but the fatal flaw of the United States Constitution, they believed, was that it created divisive party politics. Instead, conservatives built the new Confederate government by striving for the idealism of 18th-century non-party republicanism. “The constitutional revisions,” Rable concluded, were thus “both progressive and reactionary, designed both to reform politics and to restore a mythic past.” Initial military successes, the seemingly irreproachable character of President Jefferson Davis, and the 1861 elections (conducted without political parties) all seemed to confirm the success of the Confederacy’s revolution against partisan electioneering and patronage.

And yet the Confederacy’s 1862 military reverses created internal divisions that leaders could not channel through political parties. As in the United States, there were nationalists (led by Davis) insisting that defense of such a large country necessitated strong central government. But there were also those who championed more localized and limited government to protect individual freedom. These factions, often fueled by political ambitions and pettiness, clashed over such issues as conscription and habeas corpus, even as both appealed to republicanism. These fractures (dividing even Davis from his vice president, Alexander Stephens) revealed that white southerners were not as united as they supposed on issues such as centralization and state’s rights. Thus, the Confederate government, according to Rable, eventually reverted “to the intensely personal and vicious preparty politics of the founding fathers.” Nevertheless, Rable argued, the Confederacy’s demise did not stem from these internal stresses; indeed “what was most impressive,” he concluded, “was not the spread of disaffection but the persistence of loyalty to the Confederate government.”

In labeling The Confederate Republic his only thesis-driven work, Rable makes a significant distinction between it and his other books. His first two books had resulted from collecting information to deliver readable narratives about people facing obstacles, and then inductively mining conclusions from those experiences. The Confederate Republic, by contrast, traced a single idea—republicanism—over the Confederacy’s lifespan. Instead of waiting until the evidence was in before drawing conclusions—as he had in But There Was No Peace and Civil Wars—Rable started with an idea and deductively tested it with evidence. Mark Grimsley noticed this, arguing that Rable’s focus on the writings and friction among Confederate elites was “quite understandable,” but examining the views of the masses (as Rable had focused on in previous works) might have produced different conclusions.[5]

Still, most reviewers praised The Confederate Republic, especially because Rable seemingly responded to David Potter’s widely accepted suggestion that the Confederacy’s lack of a two-party system had impaired its operation. Indeed, this remains the primary reason Rable’s work is an important staple in the historiography of the Confederacy and Confederate nationalism. And yet despite the work’s lofty reputation and importance as a standard text on the Confederate government, Rable still feels The Confederate Republic, which garnered no major awards, was “my least successful effort.” As a result, he soon returned to his old method, a move that helped take him to the pinnacle of his profession.

Each of Rable’s first three books came in five-year increments (he calls it the “five-year plan”) while he taught at Anderson University, a small Christian liberal arts college in Indiana that he has “deep affection for” because “they took a chance on me when the job market was terrible.” Yet while he loved teaching there, his heavy load made it difficult to engage in the deep research characteristic of his developing method. Further, he desired more time for the public speaking opportunities coming his way after his publication successes.

Thus in 1998, Rable left Anderson for a large research university, filling the Summersell Chair at the University of Alabama. There he taught survey courses, conducted graduate seminars, and directed dissertations, but also enjoyed more time to speak at public events and conduct exhaustive research. Rable’s next book returned to and extended the formula he had adopted for But There Was No Peace and Civil Wars. It would become his most awarded effort and, some may argue, the quintessential model for how Civil War military history should be written.

Rable began researching what became Fredericksburg! Fredericksburg! (2002) with the intention of writing a standard Civil War battle study, the best of which were mostly non-academic studies intended for popular audiences and focused mainly on command decisions. Yet as he “stumbled along” in his massive research, it is no surprise that Rable became increasingly interested in incorporating the difficult experiences of the common soldiers and their families back home. The result, he has explained, was an exploration of “the steady rhythms of military and civilian life and … how the battle intersected with mundane and everyday matters in the armies and back home.”

Fredericksburg! Fredericksburg! has its share of familiar names, from generals Ambrose Burnside and Robert E. Lee, to nurses Clara Barton and Louisa May Alcott, and even authors Walt Whitman and Herman Melville. Yet as with his most successful books, the work is the most striking when incorporating the words and actions of more unfamiliar actors. Doing so allowed Rable to examine the battle from a host of different angles: press coverage, politics, racial dynamics, and diplomacy, but also soldier diets, desertion and plundering, and even such things as the weather, religion, disease, and funerals. Citing Rable’s exhaustive research required 137 pages of notes, detailing sources gleaned from over 50 archival repositories.

Yet Fredericksburg! Fredericksburg! is not a product of thesis-driven research, as Rable explained when interviewing at the University of Alabama. Certainly, he does not hesitate to make judgments (such as assessing Burnside’s battle plan), but Fredericksburg! Fredericksburg! is at its core a masterpiece of descriptive context that allows the reader to fully immerse in the book’s events. Structured strikingly like his mentor John D. Unruh’s best work, this is a different approach to academic history, and more akin to that of non-scholars, where jargon and historiographical arguments do not get in the way of clear prose and the sheer pleasure of reading a good story. In short, it is a style of writing that caused most of us to fall in love with history in the first place.

Rable found Fredericksburg! Fredericksburg! his most enjoyable book to create “because it was an experiment and I had no idea how it was going to turn out.” His method—exhaustive research uncovering the voices and views of the masses, determination to let the primary source evidence steer his judgments, and his succinct and clear writing—once again served him well. Indeed, the work demonstrates how historians should write military history, revealing how a battle affected cultural, social, and political dynamics in the Confederacy and the United States, and even across the Atlantic. In blending the battlefield and homefront, Rable showed that understanding any military campaign requires examining how strategy and tactics were shaped by the political and social context of the time, and vice versa. Since the publication of Fredericksburg! Fredericksburg!, many academics have followed Rable’s lead by producing important battle and campaign studies. Successfully blending military, social, cultural, and political history into riveting and readable prose is a difficult task, however, one that Rable mastered in perhaps his finest work.

Fredericksburg! Fredericksburg! also became Rable’s most awarded effort, winning him his second Jefferson Davis Award and the Douglas Southall Freeman Award. Most impressive, it also garnered the Lincoln Prize, perhaps the top award for a Civil War historian. This triple crown of awards (with a fourth coming from the Society of Military History) created Rable’s reputation as one of the most distinguished scholars of 19th century America.

Thus when Gary Gallagher and Michael Parrish began to oversee a new series for the University of North Carolina Press— the Littlefield History of the Civil War Era—Rable was the first potential author upon which they agreed. They asked him to return to his focus on Reconstruction, but he preferred instead to write a religious history of the Civil War. Strangely, given the importance the era’s populace placed on religious faith, Civil War scholars had understudied and underappreciated the topic. Rable wanted to change that, and Gallagher and Parrish agreed. The result was God’s Almost Chosen Peoples: A Religious History of the American Civil War (2010), a work that again steered Civil War history down a new path.

This time Rable was blunt: “Although this is not a thesis-driven work,” he expressed in the book’s introduction, “it does address important questions about the war’s origins, course, and meaning.” He further insisted the book was not a history of theology or civil religion, nor a study of the impact of religious values on the war’s conduct. God’s Almost Chosen Peoples was instead “a broad narrative that shows how all sorts of people used faith to interpret the course of the Civil War and its impact on their lives, families, churches, communities, and ‘nations.’” This once again required an exhaustive and patient exploration of a staggeringly wide array of sources to glean the sentiments of the often-neglected common folk.

Using a chronological structure, Rable examined such unfamiliar things as the insertion of references to God into the Confederate Constitution, the Mormon view of the war, Protestant-Catholic relationships, Federal confiscation of Southern Methodist churches, the difficulties faced by army chaplains, popular wartime hymns, philanthropic endeavors, beliefs about why the war became so destructive, and much more. God’s Almost Chosen Peoples effectively demonstrates how religious faith permeated and gave shape to nearly all aspects of the Civil War, especially in how both sides perceived and endured the great crisis wrenching apart their lives. “Religious conviction,” he concluded, “produced a providential narrative of the war” proving durable in both victory and defeat. Faith helped Americans make sense of and endure the war’s devastation, the sacrifices it required, the changes it wrought, and its staggering loss of life.

Despite Rable’s denial that the book was thesis-driven, Michael Parrish notes, “legions of reviewers and readers” of God’s Almost Chosen Peoples “have remarked otherwise.” Unsatisfied with a single thesis, Mark Noll found five: the ubiquity of the Bible, the pervasive recourse to providential explanations, the increases in personal religion and a facile civil religion, and Rable’s convincing demonstration that the Civil War was “the ‘holiest war’ in American history.”[6] Because of the importance of the Christian faith in his own life, God’s Almost Chosen Peoples is perhaps Rable’s most personal volume, a magnum opus (as Parrish described it) that won him his third Jefferson Davis Award. Yet again, Rable had produced a foundational work that still stands as the first book one should consult when delving into its particular topic.

After God’s Almost Chosen Peoples, Louisiana State University invited Rable to deliver the 2014 Walter Lynwood Fleming Lecture in Southern History, which LSU Press published the following year. His research for Damn Yankees! Demonization and Defiance in the Confederate South (2015) was certainly not thesis-driven in the same way that Confederate Republic had been. Yet Rable did begin with an important assumption: “Language matters,” he argued, because words often “carry serious and sometimes deadly consequences.” Rable again examined a broad array of published and archival primary sources, including the words of nearly 200 soldiers, but also the sentiments of about 200 other southerners from a wide swath of backgrounds (from women, to preachers, to politicians and newspaper editors). A conclusion then emerged: “By painting the adversary in the darkest possible hues,” Rable argued, Confederates turned the war into “a holy crusade” against the essence of evil. This suggests that Damn Yankees! followed God’s Almost Chosen Peoples logically as well as chronologically; for if their depictions of the enemy indeed turned the war into a holy crusade, their damnations were the Confederates’ liturgical text. Moreover, the invectives, especially when allied to religion, “lengthened the war, shaped the course of Reconstruction, and left an enduring legacy.”

Damn Yankees! garnered Rable yet another award to add to his growing list of honors, the James I. Robertson Literary Prize for Confederate History. In a review for the Journal of Southern History, Susannah J. Ural labeled the work a “masterful study” in which Rable revealed that recognizing Rebel perceptions of evil Yankees is “essential to understanding the brutality of the Civil War” and the South’s determination, despite great odds, to defend and later reclaim what they perceived as a superior society.[7] By examining the hate speech and writings the mass of southern people used to endure and make sense of the conflict, Rable yet again promoted a new realm of Civil War enquiry, providing another explanation for the resiliency of white southern resistance both during and after the war.

Thus by the time John Unruh’s impressive student decided to retire from teaching in 2016, he had published a list of widely diverse books—all of which anticipated or precipitated a shift in the field of Civil War history—that few can match. One key to understanding the books’ successes is that no one out-researches George C. Rable. He disdains works that rely on slight and cherry-picked evidence to support a weighty thesis. He painstakingly pours over an abundance of primary source research into the worlds of common people facing trauma and stresses in order to clearly narrate and understand their decisions and experiences.

Also crucial to Rable’s success is that he prefers succinct, jargon-free prose and “good old fashioned narrative.” Thus despite deft analysis and bold scholarly conclusions, his works appeal to mass audiences. Apart from his own writings, two others are critical for understanding this aspect of the Rable method. He frequently recommends journalist William Zinsser’s On Writing Well, a text he clings to when editing his words and those of his students. “Clutter is the disease of American writing,” Zinsser asserts, “we are a society strangling in unnecessary words … and meaningless jargon.”[8] Despite the expansive length of Rable’s best books, you will find none of that clutter in his writing (and hopefully none in his students’). Further, Rable’s favorite novel, Jack Finney’s Time and Again (1970), is an important influence on his method. The plot involves a government project that sends a man back into 19th-century New York to change history. What sets it apart from hackneyed science fiction is Finney’s accurate descriptions of time and place, which he based on extensive primary source research. Though fiction, Time and Again is remarkably like Rable’s best historical works: the product of immense archival research that transports readers into the past, deeply immersing them into the sights, smells, and worldviews of our ancestors.

Although now retired from teaching, Rable continues to aid his students in myriad ways, and no matter the project they can feel him looking over their shoulders urging a reduction of useless words. Meanwhile, he is again digging deep into archives, this time for a narrative about the relationship between Abraham Lincoln and George B. McClellan. He again insists his research is not thesis-driven, yet you can bet the resulting book will be the most thoroughly researched on the topic, utilizing a combination of readily available, underutilized, and obscure primary sources from an impressively large number of repositories. It will effectively place its readers in time and place with a riveting story told with clear prose, inductively concluding with bold assertions that shake up the field of Civil War history. Such a method has served him well, time and again.

Glenn David Brasher is a history instructor at the University of Alabama and author of The Peninsula Campaign & the Necessity of Emancipation (UNC Press, 2012), winner of the Wiley-Silver Prize. G. Ward Hubbs is professor emeritus at Birmingham-Southern College and author of Guarding Greensboro: A Confederate Company in the Making of Southern Community (UGA Press, 2003), winner of the Jefferson Davis Award and the James I. Robertson Literary Prize.

Endnotes

1. This interpretation of George C. Rable’s scholarship is solely that of Glenn Brasher and G. Ward Hubbs. The unattributed quotes are taken from a 2015 interview by Adam Petty and Katie Deal, published in 2017 in The Southern Historian, and from conversations with Hubbs and Brasher, or related to them by faculty members of the University of Alabama.

2. James M. McPherson, “Redemption or Counterrevolution? The South in the 1870s,” Reviews in American History 13, no. 4 (December 1985): 545–550.

3. George C. Rable, “Southern Interests and the Election of 1876; A Reappraisal,” Civil War History, 26:4, (December, 1980): 347–361.

4. Joan Cashin, “Women at War,” Reviews in American History 18, no. 3 (September 1990): 344, 346; Elizabeth Fox-Genovese, review of Civil Wars: Women and the Crisis of Southern Nationalism,” by George C. Rable, Journal of Southern History 57, no. 1 (February 1991): 121, 119.

5. Mark Grimsley, “Perfecting the Work of the Founders,” Reviews in American History 23, no. 3 (1995 September): 448–449.

6. Parrish, “Rable Gets Religion,” October 7, 2016; Mark A. Noll, review of God’s Almost Chosen People[s]: A Religious History of the Civil War, by George C. Rable, Civil War History 57, no. 3 (September 2011): 270-71.

7. Susannah J. Ural, review of Damn Yankees! Demonization and Defiance in the Confederate South, by George C. Rable, Journal of Southern History 83, no. 1 (February, 2017), 174-175.

8. William Zinsser, On Writing Well; The Classic Guide to Writing Nonfiction. Revised sixth edition. (New York: Harper Collins, 2001), 7.