New York Public Library

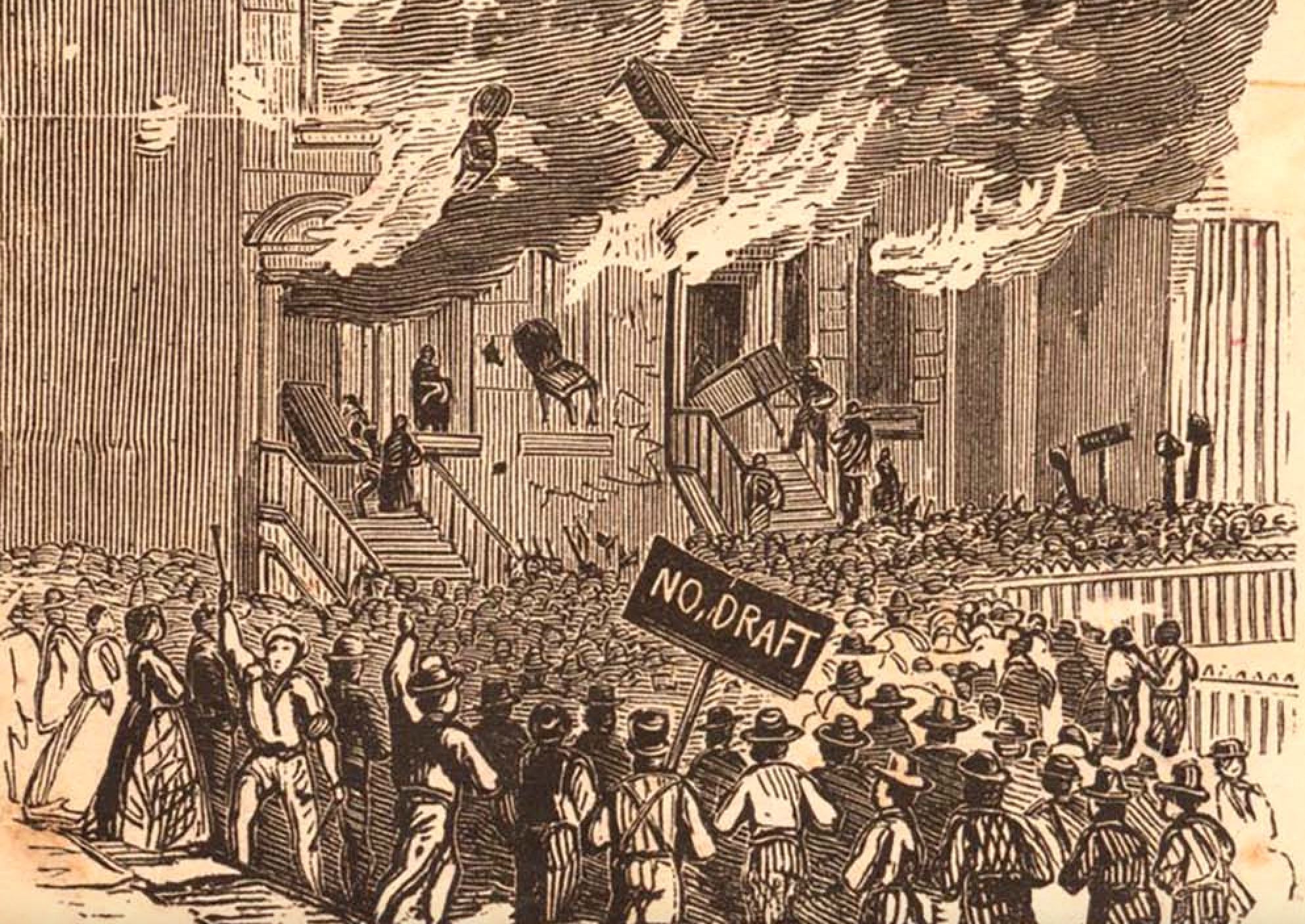

New York Public LibraryA depiction of the destruction that occurred during the New York City draft riots in July 1863.

In mid-July 1863, days after Union forces secured a victory at the Battle of Gettysburg, residents of Lower Manhattan began to riot in protest over enforcement of a previously enacted military draft law. The protesters—mostly white, working-class, foreign-born, and sympathetic to the anti-war wing of the Democratic Party—aimed their ire at public buildings, Protestant churches, the homes of pro-war or abolitionist residents, and the city’s African-American population, many of whom were killed in the violence. The arrival of Union soldiers—some of them fresh from the fight at Gettysburg—helped quell the violence. By the riot’s end, several thousand New Yorkers had been injured and several hundred killed.

During this period, Martha Derby Perry, wife of Union army surgeon John Gardner Perry, was in the city, where she was tending to her husband, who had recently suffered a severely broken leg after being kicked by his horse. Her eyewitness account of the events of July 13–16 were preserved in a letter she wrote days after the violence had ended. It is reproduced below, in full, with an introductory paragraph she provided. Both are found in the book Letters From a Surgeon of the Civil War (1906). John Gardner Perry survived the war and died in 1926 at 86. Martha died the year before her husband at 85.

After this experience my husband was laid up at home for several weeks, waiting with keen impatience for the time when he could return to his regiment. This quiet period of inaction was, however, broken by the New York Riot, which took place in the month of July, 1863. The disturbance was due to the draft made necessary by the dearth of volunteers, and also to the fear among the Irish that the negroes at the South would come North and crowd them out of their work. While it lasted the foreign, and especially the Irish, element of the city had complete control. For more than a week lawlessness reigned supreme, and though our experience was far less severe than that of many others, those who were not born when these events took place may be interested to read quotations from a letter written by me to relatives in Boston.

New York, July 20th, 1863.

Strange to say, although we knew of the intense excitement in the city and heard that many of our neighbors had been up every night, too terrified to rest, we had no idea of personal danger.

On the first day of the riot, in the early morning, I heard loud and continued cheers at the head of the street, and supposed it must be news of some great victory. In considerable excitement I hurried downstairs to hear particulars, but soon found that the shouts came from the rioters who were on their way to work. About noon that same day we became aware of a confused roar; as it increased, I flew to the window, and saw rushing up Lexington Avenue, within a few paces of our house, a great mob of men, women, and children; the men, in red working shirts, looking fairly fiendish as they brandished clubs, threw stones, and fired pistols. Many of the women had babies in their arms, and all of them were completely lawless as they swept on.

I drew the cot upon which John was lying, his injured leg in a plaster cast, up to the window, and threw his military coat over his shoulders, utterly unconscious of the fact that if the shoulder straps had been noticed by the rioters they would have shot bun, so blind was their fury against the army. The mass of humanity soon passed, setting fire to several houses quite near us, for no other reason, we heard afterward, than that a policeman, whom they suddenly saw and chased, ran inside one of the gates, hoping to find refuge. The poor man was almost beaten to death, and the house, with those adjoining, burned.

At all points fires burst forth, and that night the city was illuminated by them. I counted from the roof of our house five fires just about us, but our own danger in all this tumult, strangely enough, never crossed our minds.

The next day was a fearful one. Men, both colored and white, were murdered within two blocks of us, some being hung to the nearest lamp-post, and others shot. An army officer was walking in the street near our house, when a rioter was seen to kneel on the sidewalk, take aim, fire, and kill him, then coolly start on his way unmolested. I saw the Third Avenue street car rails torn up by the mob. Throughout the day there were frequent conflicts between the military and the rioters, in which the latter were often victorious, being partially organized, and well armed with various weapons taken from the stores they had plundered.

I passed the hours of that dreadful night listening to the bedlam about us; to the drunken yells and coarse laughter of rioters wandering aimlessly through the streets, and to the shouts of a mob plundering houses a block away, from which, as we heard later, the owners barely escaped with their lives. I must confess that as I lay in the darkness amid the uproar, there was some feeling of shelter, yes, and even rest, in having the sheet well drawn over my head, and this with no sense of heat or suffocation, although the mercury stood very high.

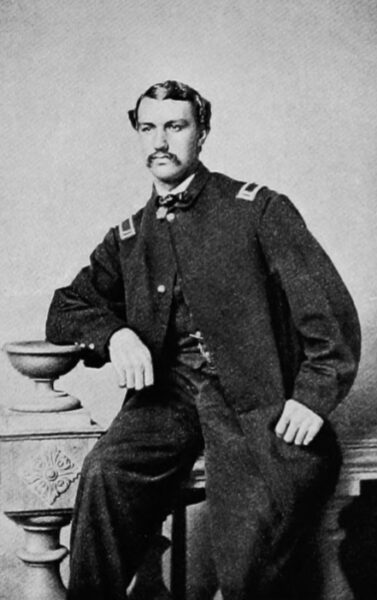

Letters From a Surgeon of the Civil War (1906)

Letters From a Surgeon of the Civil War (1906)Union army surgeon John Gardner Perry

The next morning’s news was that the rioters were murdering the colored people wherever found, and that there was no limit to the atrocities committed against them. Hurrying to the kitchen, I found our colored servants ghastly with terror, and cautioned them to keep closely within doors. One of them told me that she had ventured out early that morning to clean the front door, and that the passing Irish, both men and women, had sworn at her so violently, saying that she and her like had caused all the trouble, that she finally rushed into the house for

shelter.

Now that I began to realize our danger, I tried with all my power to keep John in ignorance of it, for in his absolutely disabled condition the situation was most distressing. The heat was intense; and during the morning I sat in his room behind closed window-shutters, continually on the alert to catch every outside noise, while watching the hot street below in the glare of sunlight. On the steps of an opposite house I recognized a policeman, whose usual beat was through our street, sitting in his shirt sleeves without any sign of uniform, looking rough and disorderly, and talking to the strolling bands of rioters. I wondered whether he was doing detective service, or whether he had joined the lawless mob. Men and women passed with all sorts of valuables taken from plundered houses.

Later in the day a crowd of boys arrived with stout sticks, threw stones at our house, called for the “niggers,” and then rushed on. This added to my alarm, I having heard that a rush of street arabs always preceded an attack by the mob. Parties of Irishmen passed and pointed to our house, and a boy ran by shouting, “We’ll have fun up here to-night.”

My heart felt overloaded as I looked at John in his helpless condition. What were we to do? Even if he were able to be moved, there was no way of accomplishing it. No amount of money could hire a conveyance; neither cars nor omnibuses were running; there was absolutely nothing to do but wait for events to guide us. During these anxious hours the realization of the meaning of personal safety grew upon me. I saw, in looking over my past, that I had accepted this great blessing all my life without a moment’s conscious gratitude. If our lives were now spared should I ever again be so unmindful?

When one of my brothers returned to lunch and reported the increasing strength of the mob, I told him of all I had seen and heard during the morning, and we considered the question of barricading the street doors and windows, but soon decided that it was useless. He then went to the police station to ask for information and help, but before leaving placed a ladder against the wall of our back yard, so that in case of attack the servants might, by this means, escape to the adjoining premises, and from there to the next street. At the police station my brother was told that, through one of their detectives who had been working in our street all the morning, they had learned that their station and also our house, with the one opposite, were to be attacked and burned that night, all being in close proximity.

The police had been already plundered of most of their firearms, and needed all their force to defend themselves. They could do literally nothing for us, but recommended barricading the front entrances to the house as well as we could.

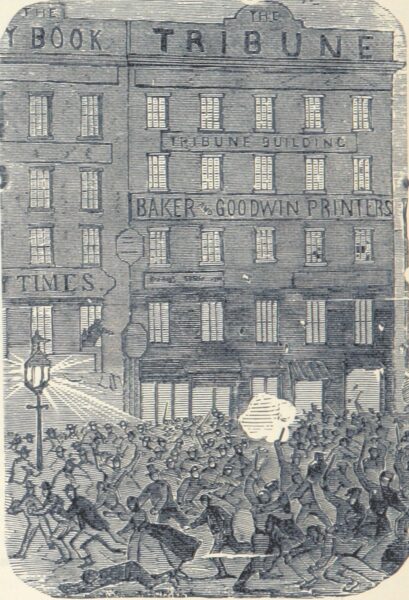

Mechanical Curator Collection

Mechanical Curator CollectionRioters attack the New York Tribune building during the violence.

The afternoon wore on, and, feeling somewhat restless from the helpless inactivity at such a time, I wandered into the different rooms of the house, looked at our valuables, locked some in trunks, tucked a few trinkets and a roll of bills into my gown, and then returned to the window-seat, feeling a little weighted with value, but better satisfied.

The city became frightfully still, and this silence was broken only by occasional screams and sharp reports of musketry.

By this time John knew pretty clearly the condition of things. He had heard the shouts in the street, and in spite of my efforts surmised the rest. The stillness grew so intense that the very atmosphere seemed a part of it, for not a breath of air stirred. As our landlord lived in the same block with us, it occurred to my brothers that in case of an attack we might escape over the roofs and pass down the skylight of his house, knowing that the very urgency of the situation would enable us to carry John with us somehow; but this privilege was refused, as the man

said it might endanger his family.

My brothers were calling at every house in the ward to induce the occupants to meet at the police station, armed with whatever weapon each could find, in order to organize and patrol the streets through the night. Meantime, our servants were instructed to remain downstairs, and not to run until the house was actually attacked, then to rush for the ladder in the back yard; and I was to cover their retreat by hiding the ladder.

These plans and directions seemed to me at the time perfectly reasonable and possible, but afterwards, when all was safe and quiet, I had many a laugh over the way I was to tear about that house while the mob was bursting in the front door—my husband up in the third story, and I, after pushing the negroes over the fence, scampering about to hide the ladder in some unknown place.

At ten o’clock that evening we were left alone in absolute darkness, as the police sent word that light would increase our danger. John lay quietly on his cot, while I again sat by the window to catch the slightest sound, and in the stillness heard a voice in the adjoining house say, “There’s always a calm before a storm,” which, under the circumstances, was not encouraging; I have never forgotten the impression it made on me.

But soon our hearts were gladdened by the sound of the patrol passing our house at regular intervals, and although we were in the third story from the street, the stillness was so intense that we could distinctly hear their conversation. Suddenly rapid pistol shots broke the spell; then came a great rush up the avenue in the darkness, John’s voice saying very calmly, “Here they come.” The absolute quiet within us both at the time from its very intensity overpowered all surface emotion. However, the noise proved to be a false alarm, and again came the silence.

Time after time we had these shocks; now the mob seemed almost upon us; then at a distance. What did it mean? Finally the tumult seemed to culminate a block away, and gradually we felt that, for the time at least, our lives were safe. As soon as the strain was over I realized how tense had been my calm, and, as we sat together the darkness, I must confess to enjoying a comfortable little weep and being much strengthened by it. Such is—myself!

During the night my brothers returned, and told us that just as the officers at the police station had agreed to combine with the citizens and patrol that vicinity, a man rushed in crying that the mob was murdering some one in our street. The whole force formed and charged up the avenue, but met only scattered bands of rioters, and these slunk away as the files of organized men appeared, stretching in solid lines from sidewalk to sidewalk, as the rioters supposed, fully armed. We heard afterward that this steadfast army, looking so formidable, while so feeble in reality, was all that saved us; that our house and the one opposite, as well as the police station, were distinctly marked by the mob for that night’s work.

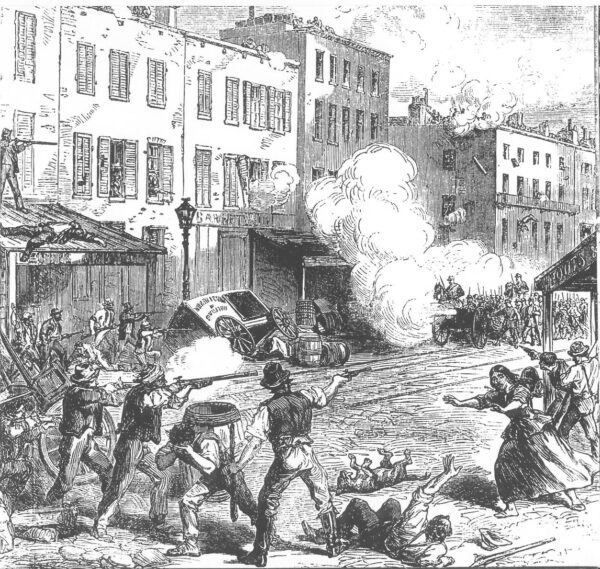

The Illustrated London News

The Illustrated London News Union soldiers fire into a group of rioters during the draft violence of July 1863.

The ensuing day was still an anxious one, but as it passed and nothing happened, we began to feel at ease again. By this time the city was full of troops, and finally the riot was quelled by firing canister into the mob. As we heard the heavy reports and responding yells, it seemed to me that I knew something of the horrors of war. To-morrow the authorities continue the draft, and I trust they will enforce it in spite of every obstacle.

Before closing this letter, I must tell you of some amusing things which happened when the citizens met at the police station, as related by my brothers on their return, and which even then gave us all a hearty laugh.

They told us that the meeting was a large one, and was called to order at seven o’clock. A vigilance committee was immediately formed for mutual protection, and a chairman and secretary selected. Resolutions were drawn up, various plans were proposed, and among others that of telegraphing to Albany for muskets—a proposition which a man of some sense suggested was worse than useless, as the mob might be upon them at any moment, reminding them also that the citizens there collected probably knew little of firearms, so that any guns would be easily seized by the mob and turned against themselves. It was then decided that the citizens could best aid the police by patrolling the streets and reporting at the Station whenever rioters were seen.

A motion was finally made, that in order to know on whom to depend, a list of the names and residences of those present should be taken. This was done with great formality and the loss of much valuable time, each man signing his name, when quite a bombshell was thrown into their midst by the suggestion that spies might be among them. At this the whole assembly seemed to separate one from the other, every man eying his neighbor with sharp suspicion. The secretary, who had been most zealous in calling the meeting, yet whose nervousness was evidently on the increase, suggested in a scarcely audible voice that if the list of names just signed should fall into the hands of the mob, the fate of each member would undoubtedly be sealed. Might it not be wiser, after all, to tear it up?

Great confusion followed these remarks; some laughed; others scoffed; but a terrified exclamation from the poor secretary silenced all. White and shaking, he pointed to the windows, which every one then saw were filled with eager, listening faces. The secretary hesitated no longer, but rushed for the list, tore it in pieces, slammed down the windows, locked the door, and even turned out the lights, before the astonished citizens knew what was happening. Then, when a mad rush for the door was imminent, as the mob outside was preferable to the suffocation and darkness within, a great commotion was heard—pounding of fists on the door, and shouts to the police that the mob was on its way there, and murdering a man in the next street. The confusion and excitement were indescribable; even the secretary forgot himself. Each man seized the club which had been provided, and soon the whole force was marching up the avenue.

Note. My husband’s leave of absence was for ninety days; at the end of that period, being eager to return to his regiment, he left for Washington on crutches. As nothing of importance occurred from the time of the riot until his departure, in September, I once more let his letters speak for themselves.