As night fell and a full moon rose in the sky, Lieutenant General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson was becoming increasingly impatient. Although he had just orchestrated one of the most successful flank attacks in military history, he wanted more.

It was May 2, 1863, and the second day of the Battle of Chancellorsville was coming to a close. The men of Jackson’s Second Corps, Army of Northern Virginia, had attacked the unsuspecting right flank of the Union army and had driven it back nearly two miles before confusion and darkness stalled the action. Anxious to continue the attack, Jackson quietly rode beyond his main battle line to scout the position. The men of the 18th North Carolina Infantry, however, were unaware that Jackson was ahead of them in the dark woods. As the general and his staff returned toward the line, the edgy soldiers mistook the riders for Federal cavalry and opened fire. Three bullets struck Jackson—two in the left arm and one in the right hand.1

With Union artillery fire showering the road around them, members of Jackson’s staff desperately tried to remove him to safety. Using the woods along the side of the road for cover, the men carried Jackson on a stretcher at shoulder height to clear the tangled underbrush. Suddenly, one of the litter bearers tripped on a vine and dropped his corner of the stretcher. The abrupt tilt caused Jackson to roll off the litter and crash to the ground. The hard fall caused further damage to the artery in his injured arm, and fresh blood began flowing from the wound.2

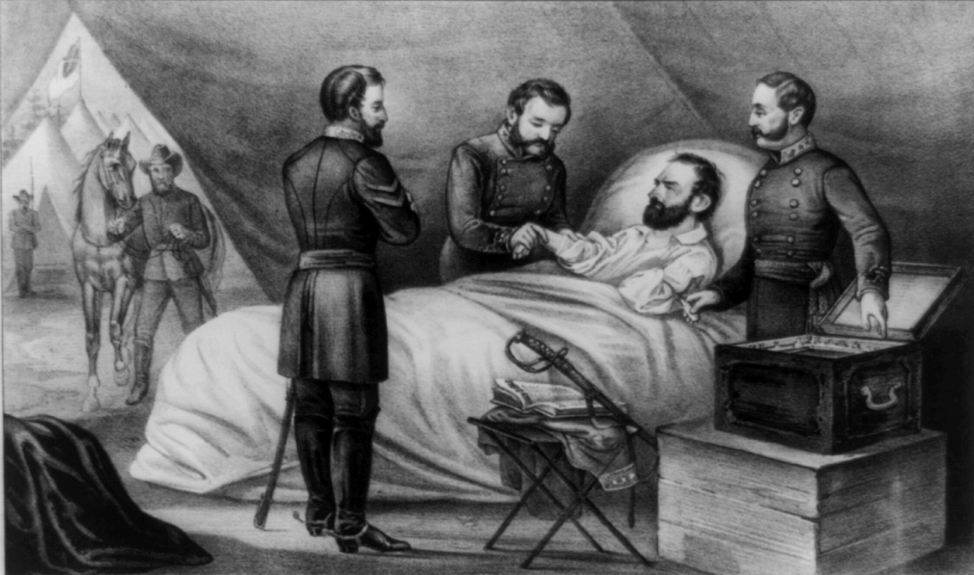

They brought Jackson by ambulance to a field hospital located one mile behind the Confederate line. Dr. Hunter Holmes McGuire, medical director of the Second Corps, arrived at the location shortly after the ambulance. Using his finger, McGuire immediately compressed the artery above the wound in Jackson’s arm, stemming the bleeding. He then rode with the general to a larger corps hospital farther to the rear. Still in shock from the loss of blood, Jackson was placed in bed and kept warm, still, and quiet. Two and a half hours later, he was deemed stable enough to undergo surgery. McGuire removed the ball from Jackson’s right hand and then amputated the left arm two inches below the shoulder.3

Jackson’s initial recovery from surgery was promising. So much so, in fact, that he was transported 27 miles by wagon to an estate near Guiney Station, Virginia, the following day; the overall plan being to evacuate him by train to his home in Lexington, Virginia, for recuperation. Sadly, however, “the great and good Jackson” would never make that journey alive.

Four days after his amputation, Jackson began to experience chest pain and difficulty breathing. A close examination by McGuire would reveal the problem – pneumonia in the right lung. Despite around-the-clock medical care, Jackson’s health would slowly deteriorate over the next three days, culminating in his death on May 10, 1863.4

Pneumonia was often a deadly illness in the 19th century. Sir William Osler, considered by many to be the father of modern medicine, described pneumonia in the late 1800s as “the most fatal of all acute diseases.” During the Civil War, the illness had a mortality rate of 24%, making “inflammation of the lungs and pleura” the third most common cause of death from disease during the conflict. But why?5

In scientific terms, the Civil War was fought toward the end of the “Dark Ages” of medicine. Bacteria had yet to be discovered as a cause of disease and, consequently, no antibiotics existed. This lack of scientific knowledge in relation to disease transmission resulted in 19th century physicians having few, if any, useful means by which to combat infections. Without antibiotics to alter the course of a serious infection, bacteria would often enter the bloodstream and lead to the systemic—and many times fatal—condition of sepsis.

Prior to the advancement of the germ theory, the contraction of disease was believed to result from an imbalance in the natural humors, or fluids, of the body—a theory dating back to ancient Greek medicine. Treatment at the time centered on removing the excess fluid from the body that was believed to be causing the disease. Fortunately, the bleeding of patients as a treatment for diseases like pneumonia was losing favor among Civil War physicians, but other harmful therapies survived. The liberal use of cathartics, or medications to purge the gastrointestinal tract, was standard treatment at the time for most diseases, including pneumonia. Depleting an ill patient of fluids through the administration of such “medicines” undoubtedly resulted in more harm than good.

Once it was discovered that Stonewall Jackson had pneumonia, his physicians began treating him with the accepted, albeit misguided, therapies of the 19th century. He was given mercury as a laxative and antimony to induce vomiting. Cupping and blistering agents were applied to his chest to “draw” the pneumonia out of his lungs and to the surface of the skin. More appropriately, he was given opium, typically in the form of morphine, to decrease his pain and make him more comfortable.6

Jackson’s physical condition and health at the time were also adversely affected by other factors. The day before his wounding, he had contracted a head “cold,” from which he was still suffering after his surgery. Additionally, Jackson had lost a large amount of blood from his injury, and he likely suffered a bruised lung when he fell from the litter. It was in this bruised lung that McGuire and the other physicians believed his pneumonia developed.7

More recently, physicians reviewing Jackson’s case have, at times, questioned whether pneumonia was his actual cause of death. Some maintain instead that Jackson died of pyemia (an early term for sepsis) that came from an infected operative site. On a pathological level, Jackson did have pyemia, but the organisms that cause sepsis must have a source from which to enter the bloodstream. In the case of Stonewall Jackson, the two most likely sources were either his operative site or his pneumonia. Dr. Hunter McGuire repeatedly documented in his later writings that Jackson’s operative site never showed signs consistent with a wound infection. His course of illness was, however, consistent with the natural history of pneumonia when it is unaltered through the use of antibiotics.8

So what was the cause of Jackson’s death? In medical terms, “cause of death” is defined as the “the disease or injury that initiated the train of events leading to death.” For Stonewall Jackson, the most likely conclusion—as his physicians maintained at the time—is that pneumonia was the initial disease triggering the sepsis that led to his death.9

Mathew W. Lively is a Professor of Internal Medicine and Pediatrics at the West Virginia University School of Medicine. His first book, Calamity at Chancellorsville: The Wounding and Death of Confederate General Stonewall Jackson, will be released by Savas Beatie LLC in May 2013.