Naval History and Heritage Command

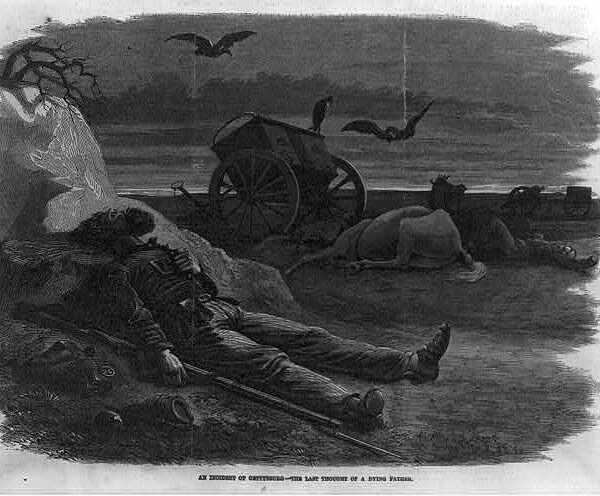

Naval History and Heritage CommandUSS Monitor sinks in a storm off Cape Hatteras on December 31, 1862.

In December 1862, USS Monitor—which had garnered national attention for its engagement with CSS Virginia in the first-ever battle of ironclad warships at Hampton Roads the previous March—was ordered to join the Union navy’s blockade of the North Carolina coast. On December 31, the vessel foundered while under tow during a storm off Cape Hatteras, her design making her unseaworthy in rough waters. After a while, Monitor capsized and sank, taking 16 of her men with her to the bottom of the sea. Among the survivors was a seaman named Francis B. Butts, who after the war penned the following account of Monitor‘s harrowing final hours.

At daybreak on the 29th of December, 1862, at Fort Monroe, the Monitor hove short her anchor, and by 10 o’clock in the forenoon she was under way for Charleston, South Carolina, in charge of Commander J.P. Bankhead. The Rhode Island, a powerful side-wheel steamer, was to be our convoy, and to hasten our speed she took us in tow with two long 12-inch hawsers. The weather was heavy with dark, stormy-looking clouds and a westerly wind. We passed out of the Roads and rounded Cape Henry, proceeding on our course with but little change in the weather up to the next day at noon, when the wind shifted to the south-south-west and increased to a gale. At 12 o’clock it was my trick at the lee wheel, and being a good hand I was kept there At dark we were about seventy miles at sea, and directly off Cape Hatteras. The sea rolled high and pitched together in the peculiar manner only seen at Hatteras. The Rhode Island steamed slowly and steadily ahead. The sea rolled over us as if our vessel were a rock in the ocean only a few inches above the water, and men who stood abaft on the deck of the Rhode Island have told me that several times we were thought to have gone down. It seemed that for minutes we were out of sight, as the heavy seas entirely submerged the vessel. The wheel had been temporarily rigged on top of the turret, where all the officers, except those on duty in the engine-room, now were. I heard their remarks, and watched closely the movements of the vessel, so that I exactly understood our condition. The vessel was making very heavy weather, riding one huge wave, plunging through the next as if shooting straight for the bottom of the ocean, and splashing down upon another with such force that her hull would tremble, and with a shock that would sometimes take us off our feet, while a fourth would leap upon us and break far above the turret, so that if we had not been protected by a rifle-armor that was securely fastened and rose to the height of a man’s chest, we should have been washed away. I had volunteered for service on the Monitor while she lay at the Washington Navy Yard in November. This going to sea in an iron-clad I began to think was the dearest part of my bargain. I thought of what I had been taught in the service, that a man always gets into trouble if he volunteers.

About 8 o’clock, while I was taking a message from the captain to the engineer, I saw the water pouring in through the coal-bunkers in sudden volumes as it swept over the deck. About that time the engineer reported that the coal was too wet to keep up steam, which had run down from its usual pressure of 80 pounds to 20. The water in the vessel was gaining rapidly over the small pumps, and I heard the captain order the chief engineer to start the main pump, a very powerful one of new invention. This was done, and I saw a stream of water eight inches in diameter spouting up from beneath the waves.

The History of Battery E, First Regiment Rhode Island Light Artillery (1892)

The History of Battery E, First Regiment Rhode Island Light Artillery (1892)Francis B. Butts

About half-past 8 the first signals of distress to the Rhode Island were burned. She lay to, and we rode the sea more comfortably than when we were being towed. The Rhode Island was obliged to turn slowly ahead to keep from drifting upon us and to prevent the tow-lines from being caught in her wheels. At one time, when she drifted close alongside, our captain shouted through his trumpet that we were sinking, and asking the steamer to send us her boats. The Monitor steamed ahead again with renewed difficulties, and I was ordered to leave the wheel and was kept employed as messenger by the captain. The chief engineer reported that the coal was so wet that he could not keep up steam, and I heard the captain order him to slow down and put all steam that could be spared upon the pumps. As there was danger of being towed under by our consort, the tow-lines were ordered to be cut, and I saw James Fenwiek, quarter-gunner, swept from the deck and carried by a heavy sea leeward and out of sight in attempting to obey the order. Our daring boatswain’s mate, John Stocking, then succeeded in reaching the bows of the vessel, and I saw him swept by a heavy sea far away into the darkness.

About half-past 10 o’clock our anchor was let go with all the cable, and struck bottom in about sixty fathoms of water; this brought us out of the trough of the sea, and we rode it more comfortably. The fires could no longer be kept up with the wet coal. The small pumps were choked up with water, or, as the engineer reported, were drowned, and the main pump had almost stopped working from lack of power. This was reported to the captain, and he ordered me to see if there was any water in the ward-room. This was the first time I had been below the berth-deck. I went forward, and saw the water running in through the hawse-pipe, an 8-inch hole, in full force, as in dropping the anchor the cable had torn away the packing that had kept this place tight. I reported my observations, and at the same time heard the chief engineer report that the water had reached the ash-pits and was gaining very rapidly. The captain ordered him to stop the main engine and turn all steam on the pumps, which I noticed soon worked again.

The clouds now began to separate, a moon of about half-size beamed out upon the sea, and the Rhode Island, now a mile away, became visible. Signals were being exchanged, and I felt that the Monitor would be saved, or at least that the captain would not leave his ship until there was no hope of saving her. I was sent below again to see how the water stood in the ward-room. I went forward to the cabin and found the water just above the soles of my shoes, which indicated that there must be more than a foot in the vessel. I reported this to the captain, and all hands were set to bailing—bailing out the ocean as it seemed—but the object was to employ the men, as there now seemed to be danger of excitement among them. I kept employed most of the time, taking the buckets from them through the hatchway on top of the turret. They seldom would have more than a pint of water in them, however, the remainder having been spilled in passing from one man to another.

U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command

U.S. Naval History and Heritage CommandThe steamship Rhode Island in a postwar photo

The weather was clear, but the sea did not cease rolling in the least, and the Rhode Island, with the two lines wound tip in her wheel, was tossing at the mercy of the sea, and came drifting against our sides. A boat that had been lowered was caught between the vessels and crushed and lost. Some of our seamen bravely leaped down on deck to guard our sides, and lines were thrown to them from the deck of the Rhode Island, which now lay her whole length against us, floating off astern, but not a man would be the first to leave his ship, although the captain gave orders to do so. I was again sent to examine the water in the ward-room, which I found to be more than two feet above the deck; and I think I was the last person who saw Engineer G.H. Lewis as he lay seasick in his bunk, apparently watching the water as it grew deeper and deeper, and aware what his fate must be. He called me as I passed his door, and asked if the pumps were working. I replied that they were. “Is there any hope?” he asked; and feeling a little moved at the scene, and knowing certainly what must be his end, and the darkness that stared at us all, I replied, “As long as there is life there is hope.” “Hope and hang on when you are wrecked “is an old saying among sailors. I left the ward-room, and learned that the water had gained so as to choke up the main pump. As I was crossing the berth-deck I saw our ensign, Mr. Frederickson, hand a watch to Master’s Mate Williams, saying, “Here, this is yours; I may be lost “—which, in fact, was his fate. The watch and chain were both of unusual value. Williams received them into his hand, then with a hesitating glance at the time-piece said, “This thing may be the means of sinking me,” and threw it upon the deck. There were three or four cabin-boys pale and prostrate with seasickness, and the cabin-cook, an old African negro, under great excitement, was scolding them most profanely.

As I ascended the turret-ladder the sea broke over the ship, and came pouring down the hatch-way with so much force that it took me off my feet; and at the same time the steam broke from the boiler-room, as the water had reached the fires, and for an instant I seemed to realize that we had gone down. Our fires were out, and I heard the water blowing out of the boilers. I reported my observations to the captain, and at the same time saw a boat alongside. The captain again gave orders for the men to leave the ship, and fifteen, all of whom were seamen and men whom I had placed my confidence upon, were the ones who crowded the first boat to leave the ship. I was disgusted at witnessing the scramble, and, not feeling in the least alarmed about myself, resolved that I, an “old haymaker,” as landsmen are called, would stick to the ship as long as my officers. I saw three of these men swept from the deck and carried leeward on the swift current.

Bailing was now resumed. I occupied the turret all alone, and passed buckets from the lower hatchway to the man on the top of the turret. I took off my coat—one that I had received from home only a few days before (I could not feel that our noble little ship was yet lost)—and, rolling it up with my boots, drew the tompion from one of the guns, placed them inside, and replaced the tompion. A black cat was sitting on the breech of one of the guns, howling one of those hoarse and solemn tunes which no one can appreciate who is not filled with the superstitions which I had been taught by the sailors, who are always afraid to kill a cat. I would almost as soon have touched a ghost, but I caught her, and, placing her in another gun, replaced the wad and tompion; but I could still hear that distressing howl. As I raised my last bucket to the upper hatchway no one was there to take it. I scrambled up the ladder and found that we below had been deserted. I shouted to those on the berth-deck, “Come up; the officers have left the ship, and a boat is alongside.”

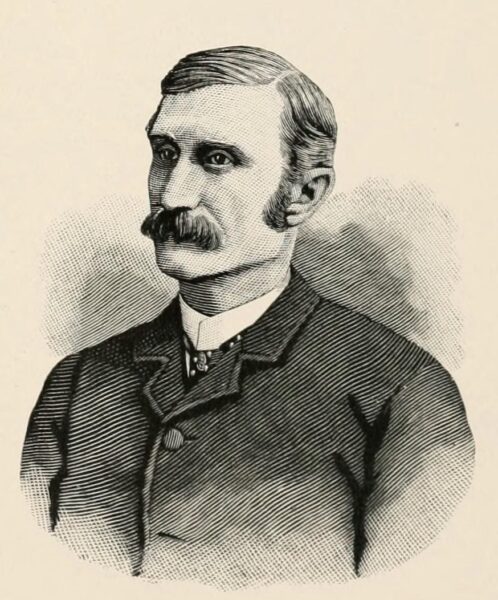

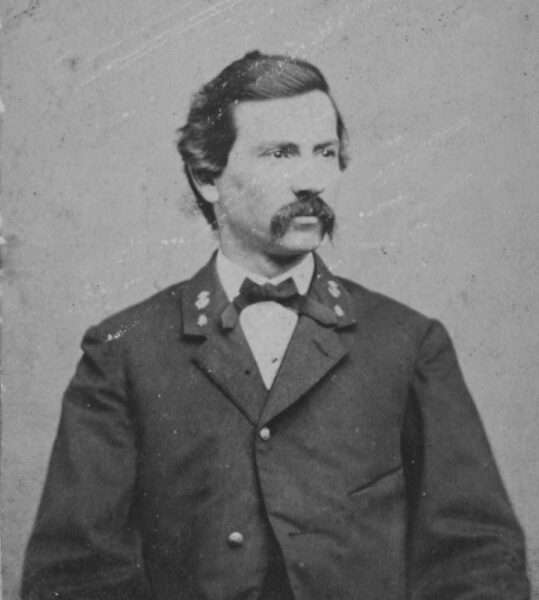

Naval History and Heritage Command

Naval History and Heritage CommandLieutenant Commander Samuel Dana Greene

As I reached the top of the turret I saw a boat made fast on the weather quarter filled with men. Three others were standing on deck trying to go on board. One man was floating leeward, shouting in vain for help; another, who hurriedly passed me and jumped down from the turret, was swept off by a breaking wave and never rose. I was excited, feeling that it was the only chance to be saved. I made a loose line fast to one of the stanchions, and let myself down from the turret, the ladder having been washed away. The moment I struck the deck the sea broke over it and swept me as I had seen it sweep my shipmates. I grasped one of the smoke-stack braces and, hand-over-hand, ascended, to keep my head above water. It required all my strength to keep the sea from tearing me away. As it swept from the vessel I found myself dangling in the air nearly at the top of the smoke-stack. I let myself fall, and succeeded in reaching a life-line that encircled the deck by means of short stanchions, and to which the boat was attached. The sea again broke over us. lifting me feet upward as I still clung to the life-line. I thought I had nearly measured the depth of the ocean, when I felt the turn, and as my head rose above the water I was somewhat dazed from being so nearly drowned, and spouted up, it seemed, more than a gallon of water that had found its way into my lungs. I was then about twenty feet from the other men, whom I found to be the captain and one seaman; the other had been washed overboard and was now struggling in the water. The men in the boat were pushing back on their oars to keep the boat from being washed on to the Monitor’s deck, so that the boat had to be hauled in by the painter about ten or twelve feet. The first lieutenant, S.D. Greene, and other officers in the boat were shouting, “Is the captain on board?” and, with severe struggles to have our voices heard above the roar of the wind and sea, we were shouting, “No,” and trying to haul in the boat, which we at last succeeded in doing. The captain, ever earing for his men, requested us to get in, but we both, in the same voice, told him to get in first. The moment he was over the bows of the boat Lieutenant Greene cried, “Cut the painter! cut the painter!” I thought, “Now or lost,” and in less time than I can explain it, exerting my strength beyond imagination, I hauled in the boat, sprang, caught on the gunwale, was pulled into the boat with a boat-hook in the hands of one of the men, and took my seat with one of the oarsmen. The other man, named Thomas Joice, managed to get into the boat in some way, I cannot tell how, and he was the last man saved from that ill-fated ship. As we were cut loose I saw several men standing on top of the turret, apparently afraid to venture down upon deck, and it may have been that they were deterred by seeing others washed overboard while I was getting into the boat.

After a fearful and dangerous passage over the frantic seas, we reached the Rhode Island, which still had the tow-line caught in her wheel and had drifted perhaps two miles to leeward. We came alongside under the lee bows, where the first boat, that had left the Monitor nearly an hour before, had just discharged its men; but we found that getting on board the Rhode Island was a harder task than getting from the Monitor. We were carried by the sea from stem to stem, for to have made fast would have been fatal; the boat was bounding against the ship’s sides; sometimes it was below the wheel, and then, on the summit of a huge wave, far above the decks; then the two boats would crash together; and once, while Surgeon Weeks was holding on to the rail, he lost his fingers by a collision which swamped the other boat. Lines were thrown to us from the deck of the Rhode Island, which were of no assistance, for not one of us could climb a small rope; and besides, the men who threw them would immediately let go their holds, in their excitement, to throw another—which I found to be the case when I kept hauling in rope instead of climbing.

It must be understood that two vessels lying side by side, when there is any motion to the sea, move alternately; or, in other words, one is constantly passing the other up or down. At one time, when our boat was near the bows of the steamer, we would rise upon the sea until we could touch her rail; then in an instant, by a very rapid descent, we could touch her keel. While we were thus rising and falling upon the sea, I caught a rope, and, rising with the boat, managed to reach within a foot or two of the rail, when a man, if there had been one, could easily have hauled me on board. But they had all followed after the boat, which at that instant was washed astern, and I hung dangling in the air over the bow of the Rhode Island, with Ensign Norman Atwater hanging to the cat-head, three or four feet from me, like myself, with both hands clinching a rope and shouting for some one to save him. Our hands grew painful and all the time weaker, until I saw his strength give way. He slipped a foot, caught again, and with Ids last prayer, “O God!” I saw him fall and sink, to rise no more. The ship rolled, and rose upon the sea, sometimes with her keel out of water, so that I was hanging thirty feet above the sea, and with the fate in view that had befallen our much-beloved companion, which no one had witnessed but myself. I still clung to the rope with aching hands, calling in vain for help. But I could not be heard, for the wind shrieked far above my voice. My heart here, for the only time in my life, gave up hope, and home and friends were most tenderly thought of. While I was in this state, within a few seconds of giving up, the sea rolled forward, bringing with it the boat, and when I would have fallen into the sea, it was there. I can only recollect hearing an old sailor say, as I fell into the bottom of the boat, “Where in did he come from?”

When I became aware of what was going on, no one had succeeded in getting out of the boat, which then lay just forward of the wheel-house. Our captain ordered them to throw bow-lines, which was immediately done. The second one I caught, and, placing myself within the loop, was hauled on board. I assisted in helping the others out of the boat, when it again went back to the Monitor; it did not reach it, however, and after drifting about on the ocean several days it was picked up by a passing vessel and carried to Philadelphia.

It was half-past 12, the night of the 31st of December, 1862, when I stood on the forecastle of the Rhode Island, watching the red and white lights that hung from the pennant-staff above the turret, and which now and then were seen as we would perhaps both rise on the sea together, until at last, just as the moon had passed below the horizon, they were lost, and the Monitor, whose history is familiar to us all, was seen no more.

The Rhode Island cruised about the scene of the disaster the remainder of the night and the next forenoon in hope of finding the boat that had been lost; then she returned direct to Fort Monroe, where we arrived the next day.

Source: Battles and Leaders of the Civil War vol. 1 (1887)

Related topics: naval warfare