As the war ground on toward its fourth year, shortages became more and more acute, both for Southern citizens and Confederate soldiers. Even in Texas, where Federal armies had yet to occupy much territory, the combined effects of the blockade and the shortage of manpower and transport combined to cause serious logistical obstacles in keeping the troops properly fed.

For one company of the 8th Texas Infantry, garrisoned at Galveston, frustration boiled over on the last Sunday of February 1864, when the soldiers were issued as rations the carcass of a scrawny, sickly steer they deemed entirely inedible. Instead of cutting up the beef and distributing it to individual messes, the soldiers instead turned out at 9:30 a.m. with their rifles and organized a formal funeral cortege. They were joined by soldiers from other commands, as well. As Edward T. Cotham, Jr., describes in his book, Battle on the Bay: The Civil War Struggle for Galveston, the soldiers put the rejected beef on a stick and paraded it through the town in grand funereal style, under reversed arms and to the accompaniment of muffled drums. When they reached the public square in front of the courthouse, they held a mock funeral and buried it, reading a formal eulogy over the remains.1 The ceremony was, according to a contemporary account, “done by the parties quietly, soberly, and mournfully,” though the spectacle “created no little merriment.”2 The following morning, a headboard had appeared over the “grave,” inscribed with the following tribute in verse:

Died in the butcher-pen, at Galveston, on Saturday night, 27th inst., an ancient gentleman cow in the 129th year of his age. Disease: poverty. His remains were issued to the troops, and by them buried in the public square with the honors of war.

The Sabbath sun shone bright and fair,

The earth rejoiced in gladness;

But soon, ah, soon! the balmy air

Was pierced with sounds of sadness.The measured tread of feet was heard;

Then came the mourning column;

And hearts of all were deeply stirred

At sounds and sights so solemn.The dead came first, a mangled mass.

A poor old cow’s fore shoulders;

(Who died, they said, for want of grass,)

It frightened all beholders.Some rushed away in wildest fright,

And all agreed in saying

They ne’er had seen just such a sight

And some fell down to praying.The muffled drum its mournful tale

Breathed o’er this beefy Mummucks;

But sadder, deeper, came the wail

From soldiers’ empty stomachs.Then next came on, with arms reversed,

The troops, all thoughtful, slow and sad —

No money in their hungry purse,

No dinner to be had.Their manly tears fell at their feet;

(The dead was not a sinner,)

But tears will flow o’er bread alone;

no MEAT For supper, breakfast — dinner.They buried the dead with sober brow,

And thought of to-morrow’s fast —

Thus rests the ancient gentleman cow,

(His fatless ribs) at last.3

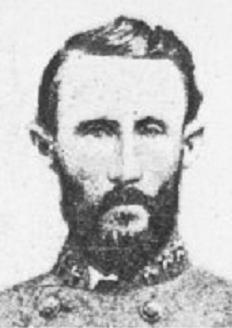

The author of those lines was later reputed to be none other than the commanding officer of the regiment, Alfred Marmaduke Hobby (1836-81). Colonel Hobby, himself not yet thirty years old, had already lived a notable life. He’d been a successful merchant at St. Mary’s, in Refugio County (near Corpus Chritsi), served in the 8th and 9th Texas Legislatures. He was a member of the Knights of the Golden Circle, and an ardent secessionist who represented his district at the Texas Secession Convention in February 1861. Hobby was also a poet of some recognition, who composed numerous works during the war. Many, including this one, would later be included in a collection of wartime poetry.4

The event quickly attracted notice in the local newspapers. The Houston Daily Telegraph reported in a dispatch from its Galveston correspondent, who noted that “the troops yesterday [Monday, February 29] refused to receive beef altogether.”5 This was soon followed by a long letter, written by a soldier signing himself “Justice,” who defended his fellows’ action and flatly rejected any notion that the spectacle pointed to serious disaffection within the regiment:

The company that took the initiative in the matter, number 117 men, and it can boast that since it has been in service (now about two years), it has never lost a man from desertion, and the men have been uniformly prompt in complying with all orders issued them by their superiors. . . any officer might well feel proud to command such men.

The movement was not dictated by any spirit of mutiny, far from it. The beef which had been issued to the Regiment for several days previous had been condemned by a Board of Survey, and pronounced unfit for use. This gave the men no relief. Their rations are not the most bountiful; nor can much be said of their quality. . . Their resolution had been taken not to receive the beef, and the burial of it was simply intended as a protest against the insult offered in persisting in sending meat, which every one, who would take the trouble to examine, could see was totally unfit to eat.6

“Have we a privileged class?”, the soldier continues. “When we entered the contest, we thought it was a cause common to all, where the hardships and privations were to be equally borne by officers and privates. The soldier looks to the officer as an example of endurance.”7

In fact, shortages such as those experienced by the 8th Texas Infantry at Galveston would only become more commonplace as the war dragged on. The hard winter of 1863-64 in Texas, where beef was generally considered easily obtained, further complicated supply problems. In early March, just at the same time the soldiers’ protest in Galveston was being reported in the local papers, Confederate Lieutenant General Kirby Smith in Shreveport issued an order authorizing the substitution of jerked or dried beef in lieu of fresh.8

Soon more pointed questions were being asked about Colonel George W. White, the Confederate commissary officer at Austin, and his procurement of beef for the army. Even where reporting the soldiers’ protest at Galveston, the Weekly State Gazette in Austin noted that when White had been sending beef to Texas troops, there had been few complaints; more recently he’d been shipping beef to troops in Louisiana and Arkansas which “is equal to the best in the market, being mostly corn fed.”9

Logistics problems would continue, and so would further protests. Notably in May 1864, the decision of the Confederate military commander at Galveston, General James M. Hawes to cease sales of flour to the families of soldiers sparked angry demonstrations by local women at both his quarters and his office. Hawes was heartily disliked already for his strained relations with local citizens – he had already earned the sobriquet “Beast Butler of Galveston” – and his reputation was done no benefit when he rounded up a group of women he deemed the be the ringleaders and put them on a train the Houston, with orders not to return.10

Andy Hall is a Texan and Southerner by birth, residence and lineage, with a family tree full of butternuts. With a background in history, museum studies and marine archaeology, Hall also writes at his own blog, Dead Confederates.

[1] Edward T. Cotham, Jr. Battle on the Bay: The Civil War Struggle for Galveston (Austin: University of Texas, 1998) 164-65. The public square where they buried the condemned beef remains a public park, where a Confederate memorial now stands.

[2] Bellville Countryman, 17 March 1864, p. 2 c. 4.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Francis D. Allen, Allen’s Lone Star Ballads: A Collection of Southern Patriotic Songs, Made During Confederate Times (Galveston, Texas: J. D. Sawyer, 1874), 169-70.

[5] Houston Daily Telegraph, 2 March 1864, p. 2, c. 4.

[6] Houston Daily Telegraph, 8 March 1864, p. 1 c. 4. The anonymous soldier’s description of company strength and readiness is almost certainly an exaggeration. Just a few weeks before, on February 16, Col. Hobby had written General Magruder’s chief of staff, Brigadier General James E. Slaughter, urging him to assign more recruits or conscripts to the 8th Texas, which had detachments scattered all along the Texas coast. Hobby urged Slaughter for assistance to “fill up four of the infantry companies of my Regiment, these companies – never large, having been raised in the most thinly-settled counties of the states – are so reduced as to be almost too insignificant to deserve the name of companies. . . The officers have appealed to me time and again to request the Major Genl & urge my petition to have them filled up. They have generously offered – if this is not done – to ask the privilege of consolidating their skeleton companies and going themselves into the ranks. . . rather than see these four Companies remain as small as they are.” A. M. Hobby to J. E. Slaughter, 16 February 1864. Alfred M. Hobby Compiled Service Record, 8th Texas Infantry, Catalog ID 586957, National Archives & Record Administration.

[7] Houston Daily Telegraph, 8 March 1864, p. 1 c. 4.

[8] Houston Daily Telegraph, 21 March 1864, p. 2, c. 6.

[9] Austin Weekly State Gazette, 16 March 1864, p. 2, c. 1.

[10] Cotham, 163-64.