Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia CommonsA watercolor of the Battle of Beecher Island by Frederic Remington

The confluence of Civil War memory and the historical legacy of the postbellum Indian wars has not received substantial attention from historians. But in the American West the two inevitably collide. One example is the struggle to create a memorial at the site of the 1868 Battle of Beecher Island.

On August 19, 1890, the United States Congress authorized the creation of the first national battlefield park, at the site of the battles of Chickamauga and Chattanooga. Just 11 days later Congress preserved the ground at Antietam to posterity. Soon to receive their federal protection were Shiloh (1894), Gettysburg (1895), and Vicksburg (1899). These sites existed as classrooms and theaters of remembrance for veterans, who returned to place monuments at their regimental high-water marks and visit the associated national military cemeteries (for Union veterans), where former comrades, known and unknown, were laid to rest. The Interior Department now manages 17 Civil War battlefield sites, as well as two affiliated national historic sites and two national monuments.

The Interior Department also administers one national battlefield park, one national monument, and two national historic sites related to the nation’s Indian wars. These sites represent several postbellum military campaigns, and two of the four are primarily associated with George Armstrong Custer: Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument and Washita Battlefield National Historic Site. The single national battlefield is the Nez Perce war site of the Battle of Big Hole, and the final location, the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site, is one of the most recent—and most contested—additions to the National Park Service site roster.

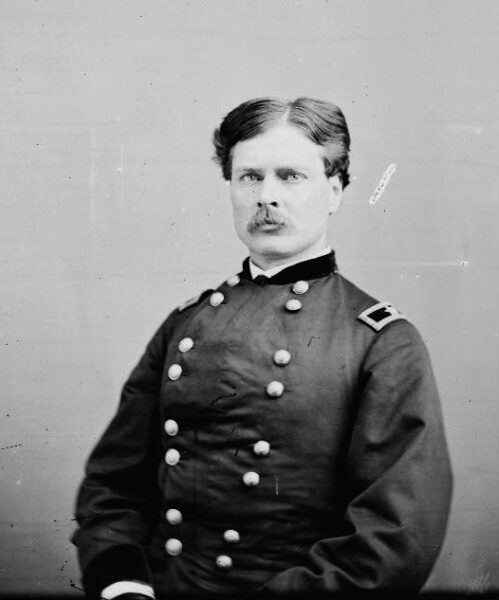

The difficulty of gaining national recognition for other sites of conflict between Native Americans and soldiers and settlers is exemplified in the failed attempt early in the 20th century to preserve and designate the site of the Battle of Beecher Island, in northeastern Colorado, as a national memorial. The battle on September 17–19, 1868, pitted a small contingent of U.S. cavalry scouts under the command of Colonel George Alexander Forsyth against Cheyenne, Arapahoe, and Oglala Lakota soldiers led by Cheyenne leader Roman Nose.

Contemporaries lauded the 50 scouts who held out against some 200–1,000 Native Americans. “The expedition of Colonel Forsyth,” the New York Herald promised, “will ever be remembered, and the annals of the frontiers will not fail to record their almost supernatural bravery.” A little more than two months after the fight on the Arikaree River, the events of George A. Custer’s battle at the Washita River eclipsed Beecher Island. But the memory of the fight had one potential savior: George Forsyth, who turned his career as a soldier into that of a writer of the army’s history.

Library of Congress

Library of CongressGeorge Alexander Forsyth as he appeared during the Civil War.

In the decades that followed the battle, Forsyth and the surviving scouts made return trips to Beecher Island, where they spoke in favor of preserving the site. In 1900, The Wray Rattler reported that the local Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) chapter had passed a resolution to ask Congress for $10,000 to build a monument on the battlefield and designate the area as a protected park. On April 12, Colorado’s U.S. Representative John F. Shafroth introduced a petition on behalf of the Colorado association to the congressional committee on public lands.

While waiting for Congress to discuss these requests, the state legislatures of Colorado and Kansas took steps to secure the land on which the battle had been fought. Newspapers eagerly followed the efforts to set aside a battlefield park. Colorado’s Salida Record believed (optimistically, if impractically) that “this battleground is of more interest than the Custer battleground, and there is no doubt that in time to come Beecher Island will be visited by thousands of Americans.” By 1904, Congress agreed to set aside 120 acres near the site for preservation. In 1905, the Colorado Legislature passed a resolution setting aside an additional 120 acres to be administered by the battlefield memorial association.

Beecher Island’s memorialists sought funding to build a monument on the battlefield, appealing to the legislatures of both Colorado and Kansas to support their effort. “It is rather unlikely,” intoned the Topeka State Journal, “that Kansas will vote money to build a monument in Colorado.” But, just three weeks later, “the ways and means committee reported favorably on a bill making an appropriation to build a monument to the Forsyth scouts.” Clarifying the reason, the Topeka State Journal explained that the scouts had entered Colorado from Kansas, giving the Sunflower State an equal interest in the commemoration process. Colorado matched the $2,500. At the annual reunion of the scouts in 1905, the association dedicated the monument. In 1916, Congress granted two condemned brass cannon to be placed at its base.

At the monument dedication, the local GAR chapter of Civil War veterans took the lead. While their efforts had resulted in the preservation of the battle site, the members suggested that the park should be used “for reunions of soldiers of the Civil War, their family and friends,” co-opting the space for the memory of their conflict.

Speeches at the dedication of the monument reflected this bias. Civil War veterans were more interested in underscoring the accomplishments of Civil War soldiers than in praising veterans of the Indian wars. Even Forsyth focused his remarks on “the two great generals of the civil war, Ulysses S. Grant and Phillip H. Sheridan.” A second speaker, Dr. C.H. Brooks, spoke of the coincidence of the Beecher Island fight occurring on the sixth anniversary of the Battle of Antietam, where “our foemen were men of tender, noble hearts and high principles of honor.” Brooks concluded that the stars worn on the chest of members of the GAR should remind Americans to “make honorable what our dead have made sacred,” leaving no doubt that he meant the Civil War dead above all.

Many veterans of the Indian wars expressed regret at the national act of forgetting that had rendered their service invisible. “Seldom, if ever, when the civil war veterans are celebrating Decoration day,” an Indian war veteran noted, “does one hear one word of remembrance for the services most arduous and heroic of the Indian war veterans, or even one word of reference to the regular army veterans.” This man blamed the GAR, because “the addresses and ‘orders’ of the Grand Army exercises at cemetery or public hall have no reference whatever to the regular army or to any decoration or record of the graves of our gallant Indian war veterans.” Seeking recognition he thought long overdue, W. Thornton Parker hoped “that at this late day the civil war veterans, who have determined to monopolize the glory of Decoration day, will see the cruel wrong inflicted on the regular army veterans of … the Indian wars, and make some pretense of reparation.” In a final damning sentence, Parker charged the GAR with an “attitude unworthy of men who wore the uniform of American soldiers.”

The efforts to create a national park at Beecher Island foundered in the decade that followed the monument’s dedication. While local GAR posts repeatedly passed resolutions to send memorials to Congress, the national government showed little interest in preserving the site. This did not stop Civil War veterans from overshadowing the story of the Forsyth Scouts. In order “to keep the matter before the public as much as possible,” explained the New Castle Nonpareil to its readers, “Denver Grand Army men will be prominent in the celebration and a meeting at Wray.” Whether or not the Beecher Island Battle Memorial Association needed the help of the GAR to make the case for memorialization, the association received it—and the National Register of Historic Places recognized the Beecher Island Battleground Memorial in 1976.

Cecily Zander is an assistant professor of History at Texas Woman’s University and a senior fellow at the Center for Presidential History at Southern Methodist University. She is the author of The Army under Fire: Antimilitarism in the Civil War Era (LSU Press, 2024). She is at work on a study of Abraham Lincoln and the American West, to be published by Liveright.