Union and Confederate veterans shake hands at the reunion to mark the 50th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg.

In his 1948 novel Intruder in the Dust, William Faulkner famously describes a Mississippi boy playing soldier—pretending to be the entire Rebel army, as it were—in the minutes preceding the disastrous Pickett-Pettigrew assault at the Battle of Gettysburg. For a fleeting moment, before James Longstreet has given the word and “it’s all still in the balance,” the boy reimagines the battle more to his liking. These altered events of July 3, 1863, gave readers a glimpse of just how profoundly the Civil War still informed the everyday lives of southerners in post-World War II America.

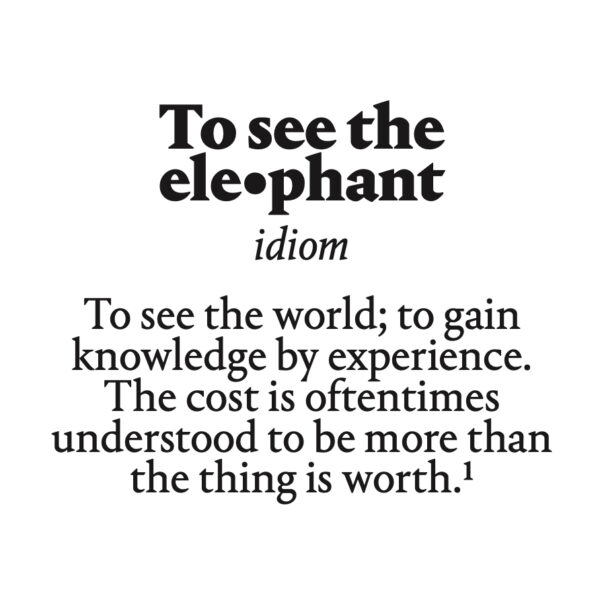

Fast-forward some 70-odd years. As the unapologetic great-grandson of a Confederate veteran, Faulkner could hardly have imagined the world of his own great-grandchildren—a Dixie in which many college students not only don’t venerate, but tear down, monuments to Robert E. Lee and his army. And there, in short, is the thing about Civil War memory: The way(s) Americans remember our national bloodletting is still, and always has been, hotly contested; always evolving; always competing; always being redesigned or adapted to fit the social, political, and cultural circumstances of the moment. Some memory narratives ascend to collective status and become part of the national consciousness. Others are gradually forgotten—or destroyed—and fade into obscurity.

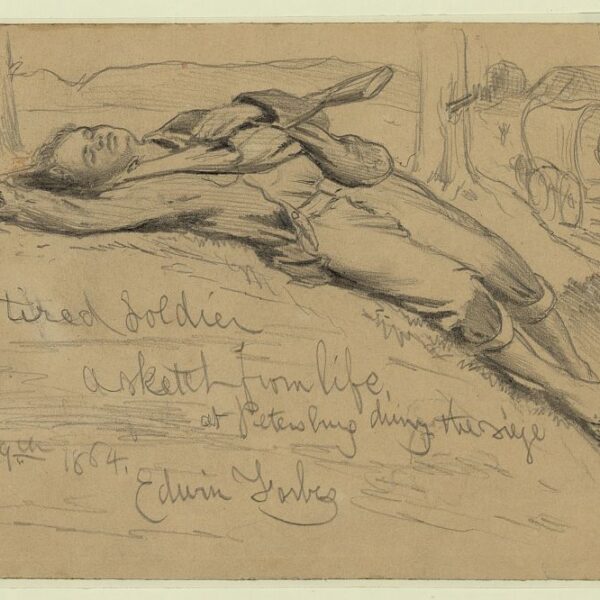

The struggle to arrange, or to dictate, how the Civil War would be remembered, and thus its role in formulating American identity, began even before the conflict ended. Thousands of soldiers published memoirs, diaries, and personal histories. Veterans from both sides organized and held massive encampments. The Southern Historical Society, founded in 1869, laid the foundation for the Lost Cause mythology that survives today. Ladies’ Memorial Associations and other heritage groups, most notably the United Daughters of the Confederacy, spearheaded massive reburial, curriculum, fundraising, and monument-building programs that peaked in the 1920s. In the century that followed, the development of national battlefield parks, the rise of the Hollywood war movie, the Civil Rights Movement, the Civil War Centennial, the phenomenon of Ken Burns’ 1990 series The Civil War, and myriad other debates—including the current one over Confederate iconography and monument removal—have forced Americans to confront how important controlling the war’s legacy remains even 157 years after Appomattox.

With that in mind, chroniclers of memory have a unique task within the realm of Civil War studies. (I say chroniclers because the list includes a poet and a journalist, not just academic historians.) They blueprint the mechanisms, organizations, mediums, and vehicles through which the conflict has been commemorated, while simultaneously revealing the motivations and meanings behind memory narratives, big and small, well-known and arcane. Many scholars of memory trace the origins of the discipline to Paul Buck’s The Road to Reunion, 1865–1900, published in 1937. Others might point to Robert Penn Warren’s The Legacy of the Civil War(1961). In either case, it took additional decades for memory studies to become a mainstream sector of Civil War history. That development came in the 1980s with the rise of institutional studies of the Lost Cause mythology.

THE LEGACY OF THE CIVIL WAR: MEDITATIONS ON THE CENTENNIAL

By Robert Penn Warren

(Random House, 1961)

Though better known for his poetry or for All the King’s Men, his 1946 novel (both won Pulitzer Prizes), Robert Penn Warren’s observations of Civil War memory have remained relevant for 70 years. They are also probably quoted more than any other work on the subject. “For the American imagination,” Warren famously declared, the Civil War functions as “the great single event of our history.” According to The Legacy of the Civil War, the conflict forced Americans from different regions to see and interact with each other, literally for the first time. It made the South more southern by way of Confederate defeat. It changed forever the American way of waging war. Warren ultimately concludes that the war has no single meaning. It cannot. It’s just too complex. And that complexity—which makes us uncomfortable and forces us to ask hard questions about ourselves as Americans and as human beings—is precisely what gives the Civil War its perpetual appeal.

GHOSTS OF THE CONFEDERACY: DEFEAT, THE LOST CAUSE, AND THE EMERGENCE OF THE NEW SOUTH

GHOSTS OF THE CONFEDERACY: DEFEAT, THE LOST CAUSE, AND THE EMERGENCE OF THE NEW SOUTH By Gaines Foster

(Oxford University Press, 1987)

Though often paired with Charles Reagan Wilson’s Baptized in Blood(1980), Gaines Foster’s Ghosts of the Confederacy is not a study of social religion nor is it a cultural dissection of Confederate commemoration. By design, the book is a detailed blueprint—a true organizational history—of the men, women, and institutions behind the founding and maintenance of the Lost Cause mythology. Beginning with the Virginia School of the 1870s—the original, Richmond-based architects of the Lost Cause, led by Jubal Early—Foster outlines how elite Confederate veterans sought to codify a history of the war that would address issues of defeat and fractured manhood in the New South. These so-called histories pinned blame for Confederate failure on James Longstreet (for want of a victory at Gettysburg, the war was lost) and contended that the Union’s overwhelming population advantage was how manlier, more honorable southerners wound up on the losing side. Perhaps most important of all, Foster documents how and why women took over the helm of Confederate heritage in the 1890s and explains their primary role as monument builders.

CONFEDERATES IN THE ATTIC: DISPATCHES FROM THE UNFINISHED CIVIL WAR

CONFEDERATES IN THE ATTIC: DISPATCHES FROM THE UNFINISHED CIVIL WARBy Tony Horwitz

(Pantheon, 1998)

Tony Horwitz, another Pulitzer Prize-winner, in his case, for journalism, was not a historian, but Confederates in the Attic—part history, part travelogue, part cultural criticism—has probably been assigned in more history classes than the rest of this list combined. That is no slight to them, merely an indication of this book’s immense popularity. For untold numbers of high school students and college undergraduates, Horwitz has served as a guide through the weird, wild, and sometimes utterly bizarre world of Confederate reenactment and commemoration. From tours of Fort Sumter, Shiloh, and Andersonville to in-depth (and sometimes pointedly awkward) conversations with Confederate enthusiasts, the last surviving Confederate widow, and even Shelby Foote (then recently made world famous by Burns’ The Civil War), Horwitz confirmed on the eve of the new millennium what Warren had argued at the beginning of the conflict’s centennial: The Civil War will always hold different meanings for different people—and its hold on Americans, and especially southerners, is never going away. In this sense, Confederates in the Attic is effectively The Legacy of the Civil War for Generation X and Millennials.

RACE AND REUNION: THE CIVIL WAR IN AMERICAN MEMORY

RACE AND REUNION: THE CIVIL WAR IN AMERICAN MEMORYBy David Blight

(Harvard University Press, 2001)

In a significant departure from the institutional histories and Lost Cause studies that predominated from the 1980s to the early 2000s, David Blight offered a meta explanation—or better still, a “genesis story”—for the Civil War legacy that took shape in the 1870s and has endured to the present. The story revolves around three ideological camps: reconciliationists (white northerners who wanted to move past the war and repair the economy), white supremacists (white southerners who refused to recognize slavery as the war’s cause and sought to preserve the color line), and emancipationists (a coalition led by African Americans who viewed the abolition of slavery as the pinnacle of the war’s meaning). According to historian Blight, for the sake of a quicker and racially beneficial process of reunion, reconciliationists and white supremacists allied to suppress emancipationist interpretations of the war, and established the narrative of mutual honor and sacrifice still common today. Since its release in 2001, Race and Reunion’s thesis has been critiqued and expanded upon—most notably by Caroline Janney in Remembering the Civil War: Reunion and the Limits of Reconciliation(2013)—but it remains the gold standard.

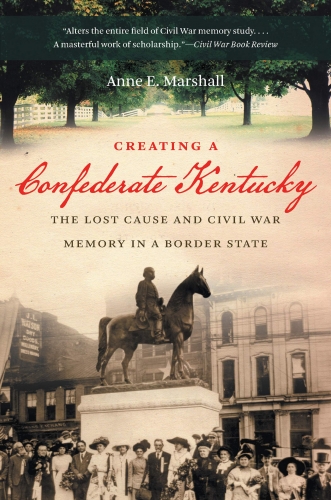

CREATING A CONFEDERATE KENTUCKY: THE LOST CAUSE AND CIVIL WAR MEMORY IN A BORDER STATE

CREATING A CONFEDERATE KENTUCKY: THE LOST CAUSE AND CIVIL WAR MEMORY IN A BORDER STATE By Anne Marshall

(University of North Carolina Press, 2010)

By the time Anne Marshall’s Creating a Confederate Kentucky was published in 2010, southern historians had spent decades repeating E. Merton Coulter’s quip that Kentucky waited until the war was over to secede and become Confederate. Likewise, many a lecturer on the postwar South noted that Kentucky, despite having contributed tens of thousands more soldiers to the Union than to the Confederacy, became one of only two non-seceded states whose racial violence necessitated a branch of the Freedman’s Bureau during Reconstruction. But Marshall was the first historian to look seriously at the border states and explore how political, social, and cultural wartime experiences rooted uniquely in geography could—and in the case of Kentucky, did—equate to unique postwar commemorative developments. To establish a southern (read: pro-Confederate, Democratic) identity for themselves, white Kentuckians adopted the extra-legal violence as well as the Lost Cause rhetoric and rituals of neighboring ex-Confederate states and effectively “disappeared” Kentucky’s Unionist past for generations. Creating a Confederate Kentucky kicked off a wave of memory studies focused on other border states, postwar counternarratives, and homefront violence.

MATTHEW CHRISTOPHER HULBERT IS ELLIOTT ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF HISTORY AT HAMPDEN-SYDNEY COLLEGE. HE IS THE AUTHOR OF THE GHOSTS OF GUERRILLA MEMORY: HOW CIVIL WAR BUSHWHACKERS BECAME GUNSLINGERS IN THE AMERICAN WEST(UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA PRESS, 2016), WHICH WON THE 2017 WILEY-SILVER PRIZE, AND THE CO-EDITOR OF THE AMERICAN WARS AND POPULAR CULTURE BOOK SERIES AT LSU PRESS.

Related topics: legacy