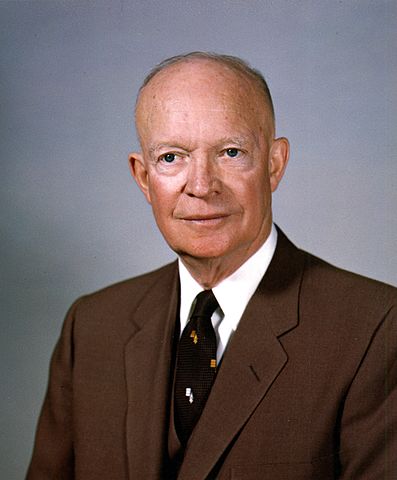

February 1959 White House portrait of President Dwight D. Eisenhower

In the fall of 1950, General Dwight D. Eisenhower and his wife, Mamie, signed a contract to purchase a 189-acre farm south of the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Ike was 60 years old, and he was planning his retirement. Mamie and he had moved numerous times during his illustrious military career, and they had never owned a home. Both of them saw the potential of this idyllic farm that bordered Gettysburg National Military Park to the east.

Ike’s first trip to Gettysburg occurred in May 1915 as a senior at the United States Military Academy. His entire class came to Gettysburg to study the history, strategies, and tactics of the battle. Over Ike’s lifetime, he became a serious student of the Civil War, as well as an expert on the Battle of Gettysburg.

Ike’s second trip to Gettysburg took place under very different circumstances. World War I was raging in Europe, and a 27-year-old Captain Eisenhower was trying to get orders to France. Instead, Ike was ordered in the spring of 1918 to Camp Colt in Gettysburg. The tank training camp was located on hallowed ground where Major General George Pickett made his charge on the third day of the Battle of Gettysburg.

When Ike bought the farm from Allen Reading in 1950, it had been 87 years since the Battle of Gettysburg. There had been several owners of the farm since 1863. During the battle, John Biesecker was the owner. He had bought the farm in 1851, and he sold it in 1865. When traveling south along Confederate Ave. just beyond the Longstreet Tower in the Gettysburg National Military Park, there is a marker for Biesecker Woods. The woods head west toward the Eisenhower Farm.

The main house on the Eisenhower Farm in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. This view looks east toward Biesecker Woods and Confederate Ave.

In 1863, John Biesecker was renting his farm to Adam Bollinger. As a tenant farmer, Bollinger was supporting his wife and two small children on this land. His father, Jacob Bollinger, was renting and living on the farm directly south of the Biesecker Farm. During the spring of 1863, Adam had planted wheat, corn, and oats in his fields. By July 1863, his wheat was getting close to harvesting. He also had a modest herd of cows. He maintained the fences that separated the different fields of the farm.[i]

On the first day of the battle, July 1, 1863, the intense fighting was northwest, north, and northeast of the Biesecker Farm. Adam Bollinger and his family remained on the farm, probably optimistic that the battle would stay to the north. The senior military officers on both sides had different thoughts.

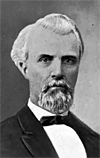

The Confederates were heading south to form their right flank, and Union cavalry under Major General John Buford was trying to observe and monitor Confederate troop movement to the south. On the evening and night of July 1, the Union troopers, anticipating a Confederate drive to the south, formed lines east of the Biesecker Farm on the west side of the Emmitsburg Road.[ii]

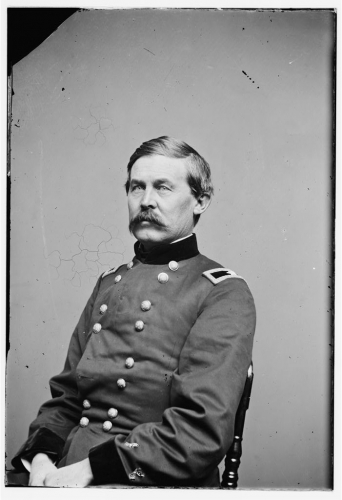

Union general John Buford

A major obstacle that the Confederates had to overcome on the first day and part of the second day of the Battle of Gettysburg was South Mountain. It is part of the Appalachian Range. For a large army in the 1860s, the mountain was a logistical nightmare.

The majority of General Robert E. Lee’s extended troops in Pennsylvania were on the other side or west of South Mountain close to Chambersburg. This meant that Lee’s forces had to travel from Chambersburg to Gettysburg on the narrow Chambersburg Pike, which in the 1860s was a difficult and arduous journey through the mountain pass. There was significant congestion and backup on the pike on the first day and part of the second day of the battle.

On the second day, General James Longstreet, the commander of the Army of Northern Virginia’s First Corps, was ordered—after initial disagreement between General Lee and himself—to head south from the Chambersburg Pike at Herr’s Ridge and determine the location and size of the Union’s left flank. The gridlock on the Chambersburg Pike significantly hindered two of Longstreet’s divisions. Major General John Hood’s division and Major General Lafayette McLaws’ division were not fully prepared to march south until approximately 1 p.m. on the battle’s second day. Major General Hood was waiting for Brigadier General Law’s brigade to arrive. Many of the men in Hood’s division had already marched 18 miles on the second day and desperately needed water.

As the two Confederate divisions were heading south along Blackhorse Tavern Road, senior Rebel officers thought that their troops were too exposed to the United States Signal Corps observers positioned on Little Round Top to the southeast. To avoid detection, the two divisions were shifted slightly west to Willoughby Run, which provided tree cover along the banks of the creek. During this difficult march south, Confederate intelligence and scouting reports revealed that the Union army lines were farther south than originally thought. Union cavalry had spotted the Confederate movement to the south and reinforced their lines west of the Emmitsburg Road.[iii]

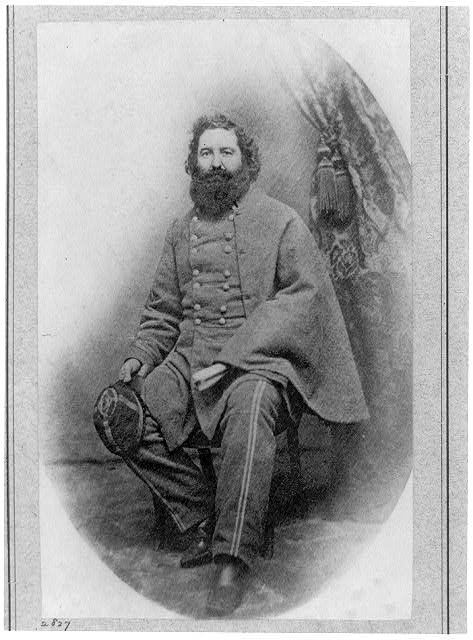

Major General Lafayette McLaws

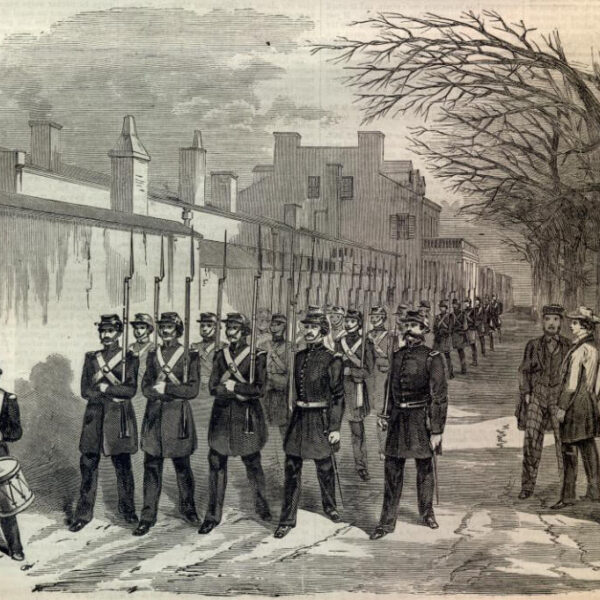

At approximately 2 p.m. on the battle’s second day, Major General McLaws’ division left the cover of Willoughby Run and proceeded east to what became known as Confederate Ave. Two of his four brigades, commanded by Brigadier General Barksdale with his Mississippi infantrymen and Brigadier General Wofford with his Georgia soldiers, were positioned in tandem north of Millerstown Road along Confederate Ave. The other two brigades, commanded by Brigadier General Kershaw with his South Carolina infantrymen and Brigadier General Semmes with his Georgia soldiers, were deployed in tandem south of Millerstown Road along Confederate Ave.

Once Kershaw’s and Semmes’ brigades left Millerstown Road just east of the Pitzer Schoolhouse and started marching southeast through the farm fields to Confederate Ave., they entered the Biesecker Farm.[iv] The soldiers started receiving U.S. artillery fire at about 2 p.m. Trying to get into position and find cover as soon as possible, they had no regard for crops in the fields. The nearly ripe wheat was trammeled. Any fences along the marching route presenting an obstacle were torn down. By approximately 3 p.m., most of Kershaw’s and Semmes’ brigades were in position along Confederate Ave. and Biesecker Woods. The soldiers were digging breastwork for protection from enemy artillery.

Shortly after McLaws’ division was deploying east and southeast to Confederate Ave., Hood’s division commenced its deployment in a southeasterly direction right through the western and eastern fields of the Biesecker property.[v] The wheat, corn, and oats were trammeled. The fences were torn down. Hood’s division had to endure more Union artillery because they had a greater distance to cover. Most of the rounds went over their heads and landed in the eastern fields of the Biesecker Farm.

Adam Bollinger and his family did not evacuate their house until Hood’s division was marching through the front yard. He now had over a division of Rebel troops on his land. The Confederates told him that things were going to get hot, and he needed to leave immediately. Adam and his family headed south to his wife’s family farm.

As Hood’s division marched east and southeast through the Biesecker Farm, two brigades positioned themselves next to the far right of the brigades of McLaws, Kershaw, and Semmes. Brigadier General Robertson’s brigade with mainly Texas soldiers and one regiment of Arkansas infantrymen was next to Kershaw’s brigade. Immediately behind Robertson’s brigade in tandem was Brigadier General Anderson’s brigade with Georgia soldiers. Anderson was next to Semmes’ brigade.

From the point where the two brigades of Hood’s division were contiguous to McLaws’ brigades, Robertson’s and Anderson’s lines extended south and southeast through the entire eastern part of the Biesecker Farm and Woods and continued to another property.[vi] Once the two brigades were in place along Confederate Ave., they too started digging breastworks to protect themselves from Union artillery.

A view of the Eisenhower farm, looking west from Biesecker Woods

The other two brigades of Hood’s division formed the far right flank of the Confederate lines during the battle. Like the other brigades, they were positioned in tandem, and their lines were contiguous on the left to Robertson’s and Anderson’s brigades. The brigade of Alabamians in front was commanded by Brigadier General Law. Law became the acting division commander when Hood was wounded during the second day of the fighting. Immediately behind Law’s troops were soldiers from Georgia.[vii] Their commander was Brigadier General Benning. These two brigades completely traversed through the Biesecker Farm while getting into position, but their lines along Confederate Ave. were beyond the boundaries of the Biesecker Farm.

All of Hood’s division was not in place along Confederat Ave. until between 3 and 4 p.m. on July 2. They had the greatest distance to march, and they were under enemy artillery fire for the longest period of time. Most of the men had marched over 20 miles already on the second day, and they had very little time to rest and look for water. Once in position, they were expected to dig breastworks. In a short time, they were ordered at approximately 4 p.m. to advance toward the Round Tops.[viii]

Once the Confederate troops advanced to the east at about 4 p.m., the Biesecker Farm regained its calm. The artillery shells that had been consistently landing in the eastern fields became sporadic. There were wounded and walking wounded soldiers on the property. The farm house and barn were used as field aid stations.[ix] Since the Biesecker Farm was located too close to the battlefield, it was not designated as a field hospital.

Although there was relative calm on the farm after the Confederate advance, there was still significant damage being done to the Biesecker property. Heavy artillery trains pulled by draft horses and mules further damaged the crops and the fields as they moved into position. Following the artillery trains were supply trains and reserve artillery trains. The support soldiers from the reserve trains used posts from the fences for camp fires. There were also stragglers and looters on the property.[x]

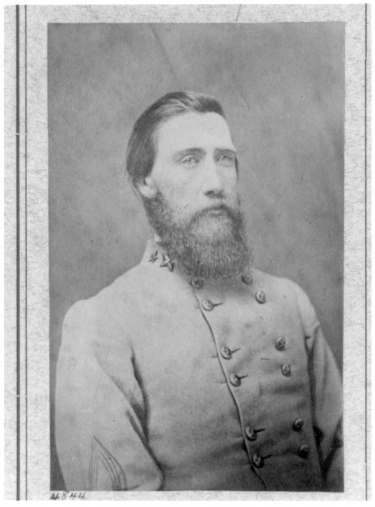

Confederate general John Bell Hood

The beginning of the third day of the battle was quiet on the Biesecker Farm. The Confederate soldiers of McLaws’ and Hood’s divisions who had traversed through the Biesecker Farm on the previous day were positioned east of their original breastwork on Confederate Ave. The intense fighting at Devil’s Den, Little Round Top, the Peach Orchard, and the Wheat Field on the afternoon and evening of the second day had ended primarily because of darkness.

The morning calm on the third day of the battle ended around noon. General Lee ordered an intense artillery barrage on the Union lines. During this bombardment, the right flank of the Confederate lines faced a challenge from the Union cavalry. Brigadier General Kilpatrick’s and Brigadier General Merritt’s mounted forces attacked the Rebel right flank from the south. To check the attack, Confederate Brigadier General Law redeployed some of his forces to the south.[xi] The last thing the Confederates wanted during Lee’s artillery barrage and the subsequent infantry advance was enemy cavalry behind their lines.

To reinforce their right flank and to counter the Union horsemen, the Rebels also sent Georgia reserve regiments from Semmes’ brigade. These reserves had to march southwest at quick time through the Biesecker Farm and were positioned on the farm south of the Biesecker Farm.[xii] The Confederate counter actions were able to halt the Union cavalry, which made the mistake of attacking fortified Rebel infantry positions. Some of the cavalry compounded this error by dismounting and fighting the veteran Rebel infantry with their carbines.

By approximately 2 p.m. on the third day of the battle, the intense Confederate artillery barrage ceased, and Pickett’s Charge commenced. The six brigades of McLaws’ and Hood’s divisions were not ordered to advance during Pickett’s Charge. Some of the soldiers were checking the Union cavalry attack. After the devastating defeat of the Confederate assault, General Longstreet ordered the six brigades to retreat to their original breastwork along Confederate Ave. Concerned about a Union counterattack, he had his troops expand and dig more breastworks.[xiii]

The improved breastwork that resulted from this work was known as Anderson’s Breastwork. This enhanced entrenchment covered the entire eastern boundary of the Biesecker Farm and extended southwest though Biesecker’s southern property line.[xiv] The breastwork then continued and stretched southwest to the farm rented by Jacob Bollinger.

After the expected Union counterattack did not materialize, the defeated Confederate forces started their retreat to Virginia on July 4 and 5. Many of the soldiers used the cover of darkness for their withdrawal. The six Confederate brigades and their support troops who deployed through the Biesecker Farm on the second day of the battle now retreated through the same fields. The Biesecker Farm received even more damage.

When Adam Bollinger returned to the Biesecker Farm after the Confederate retreat, he found his livelihood destroyed. His cows had been slaughtered. All of his crops had been trammeled. His fences were torn down, and many of the fence posts had been used for firewood. The contents of his house and barn had been looted.[xv]

The State of Pennsylvania was slow in establishing a Battle of Gettysburg compensation fund for the affected citizens of the town. Finally, the Act of April 9, 1868, was created to assist and provide funding for the people of Gettysburg with financial claims. Adam Bollinger filed a claim for $441.82. While it was approved, Pennsylvania officials never appropriated funds to pay it.[xvi]

After 11 years of no recompense, Bollinger decided to file a federal claim with the U.S. Army Quartermaster Corps. The amount of his claim increased dramatically to $1,707.30. After a review by the Quartermaster Corps, the claim was rejected on the grounds that no Union soldiers had benefitted from his property during the battle.[xvii]

The Eisenhower Farm in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, played a significant role during the second and third days of the fighting at Gettysburg as the location for the deployment, staging, and support for six brigades of Confederate soldiers. The farm is not commonly looked upon as part of the battlefield, but the six brigades did receive intense artillery fire in the eastern sections of the farm during their deployment on the second day.

Dennis Edward Flake is a seasonal park ranger at the Eisenhower National Historic Site in Gettysburg. He has interpreted history at six National Park sites and is the author of three history books and many articles and book reviews.