Holt Collier (c. 1845-1936) was a Mississippi slave who went off to the Civil War as a servant to his master, Howell Hinds, and Hinds’ son Tom. Although he was only a teenager himself, Collier was already an experienced hunter and tracker, and quickly found himself acting as a scout for several Confederate units, including the 9th Texas Cavalry. After the war he spent time as a cowboy in Texas, but eventually returned to Greenville, Mississippi, where he spent the rest of his life.

Collier’s skill as a hunter was legendary; he reportedly killed over 3,000 bears during his lifetime. Collier served as a hunting guide for President Theodore Roosevelt twice, on bear-hunting expeditions in Mississippi in 1902, and again in Louisiana in 1907. It was during the Mississippi outing that Collier cornered a female bear. While Collier waited for Roosevelt and his party to come up, the sow managed to take a swipe at one of the guide’s tracking dogs, killing it. Collier knocked the sow unconscious with his rifle and tied it to a tree. When the president arrived he declined to shoot the helpless animal, which was later erroneously described in press accounts as a bear cub. And so, the legend of the Teddy Bear was born.

But a more remarkable event happened five years later, on Roosevelt’s 1907 bear-hunting expedition to Louisiana. The press were kept away this time, so the story didn’t get a lot of coverage, and seems to have been overlooked by most researchers in the 100-plus years asince. It’s a story told, of all places, in an obscure academic journal that (maybe) no one’s read in the last 70 years or so:

A wild hog is no different from our domestic sluggard that fattens in a sty. The best breeds are turned loose by their owners — Duroc-Jerseys, Poland Chinas, Berkshires, Essex — and no animal reverts to type, or goes native, more promptly than a pig. He may have been pampered as the household pet, but one brief taste of freedom makes him the most dangerous brute that ranges our forests, the only creature that deliberately and wantonly attacks a man. Instead of a slothful animal that dozes in his wallow, we find the razorback, powerful, vicious and swift as lightning. When he grows old, and young boars combine to drive him from the herd, the ousted monarch retires to solitude, gnashing his teeth and brooding over his wrongs; then it’s wise to let that fellow alone. A wolf won’t venture near, nor a bear or panther. Two enormous tusks curl upward and backward from his lower jaw, like curving scimitars of ivory, that by one sidewise swipe will disembowel a dog.

Some woodsmen contend that the tusks of a domestic boar grow much longer after he goes native, because he uses them more, and nature develops a weapon to meet his needs. Other keen observers say that this is not true; that the tusks of a boar in captivity will be about the same length as those of one that has gone wild. The wild boar, however, shows less fat about the jowls, so that more of his gleaming ivory is exposed. When he comes charging through the brushwood, it’s a fearsome sight, and the fleeing tenderfoot is apt to overestimate his tusks.

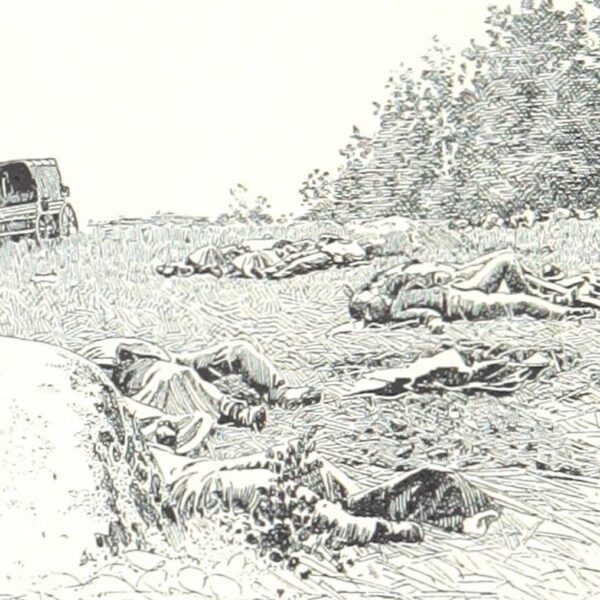

One pair found by Governor Parker measured seven and five-eighths inches, taken from the boar that attacked Doctor [Presley Marion] Rixey, personal physician to President Theodore Roosevelt, while Teddy was on a hunting expedition. This infuriated devil might have slain Doctor Rixey, if Holt Collier, the celebrated Negro hunter, had not thrown himself between them, grappled the beast and stabbed him to death. Doctor Rixey, I am told, now has his tusks as a souvenir of luck. [1]

Damn. Collier was in his early sixties at the time. And it was Rixey who walked away with the tusks as a souvenir? What?

Andy Hall is a Texan and Southerner by birth, residence and lineage, with a family tree full of butternuts. With a background in history, museum studies and marine archaeology, Hall also writes at his own blog, Dead Confederates.

__________

[1] Charles Knapp, “Hogs Roman and Boar Hunting, Ancient and Modern.” The Classical Weekly, Vol. XXVII, No. 11, January 7, 1935, 84.

Related topics: African Americans