Rear Adm. David Farragut famously “damned the torpedoes” when he closed off the port of Mobile as a haven for blockade runners. But the Union navy’s and army’s final push along the Gulf Coast in the spring of 1865 found “these hidden instruments of destruction” remained in the bay’s waters and on roads leading to its forts. Much to sailors’ and soldiers’ chagrin, even after Mobile Bay was repeatedly swept, mines—called torpedoes in the Civil War—claimed river monitors Milwaukee and Osage in late March.1

Lieutenant Commander William H. Gamble, commander of the Osage, reported that he had moved out of the way of another ironclad and was about to drop anchor “when a torpedo exploded under the bow, and the vessel immediately commenced sinking.” He reported two sailors were killed in the explosion, was unsure about how many were wounded below deck but confirmed three sailors were wounded on deck. “The wounded were conveyed to the nearest ship for medical attendance.”2

Such wounds could be gruesome. Jan Herman, recently retired as the Navy Medical Department’s senior historian, explained that “In the case of an ironclad, an underwater explosion might drive the metal fragments inward causing penetrating wounds.” Those below deck were burned, blinded, and suffered ruptured ear drums. Despite the serious nature of such wounds there are few pages devoted to these injuries in the multi-volume Medical/Surgical History of the War. Like their British counterparts in the Crimean War, who also found themselves treating mine casualties, the surgical reports concentrated on gunshot wounds.3

“Torpedoes” were the improvised explosive devices of the Civil War. They slowed General George McClellan’s advance on Richmond, closed the James River to the Union navy, broke up assaults on Fort Wagner outside Charleston and wreaked havoc in the attack on Spanish Fort below Mobile. These hidden weapons were regarded as such a threat that Union commanders put prisoners of war and suspected guerrillas into rail cars to cross booby-trapped bridges, lead river sweeping parties, or march in front of infantry down country roads. The effectiveness of detection mattered little, however, and there were casualties. To save lives, treatment needed to be immediate. The only combat medicine encouraged by Union surgeons was a demand that soldiers know how to use Lambert tourniquets. Whereas today’s combat lifesaving has survival rates among wounded approaching 90 percent, in the Civil War this was closer to 50 percent.4

Shortly after the war ended, Dr. S.W. Gross, the son of the author of the army’s prewar surgical manual, recorded his notes from five operations in a front-line field hospital on Morris Island. In his five cases, all survived their operations, but one, Sergeant Thomas Mack, died later from complications. Gross admitted that during the two operations on the New Hampshire infantryman’s right leg and ligation of the femoral vein, “the orifices of the wounded vessels could not be discovered.” He was given morphine “and a nutritious diet and stimulations freely administered.”5

Private Peter Riley, an artilleryman from Rhode Island, had, in the blast from a “metallic exploding apparatus” on September 10, 1863, “the entire anterior parts of the leg with bones … carried away, [with] a small portion of the tibia remaining.” The knee joint and its cartilage and the thigh bone above the knee also were fractured. It took another operation to control the bleeding. He then slipped into “slight traumatic delirium” for an unrecorded time. He was next transferred to Beaufort for more surgery in October. “On the 10th of November the man had entirely recovered.” Writing before Louis Pasteur’s germ theory was accepted and Joseph Lister had published his findings on “antiseptic surgery,” Gross attributed his overall success “to perfect quietude, fresh air and a nutritious diet.”6

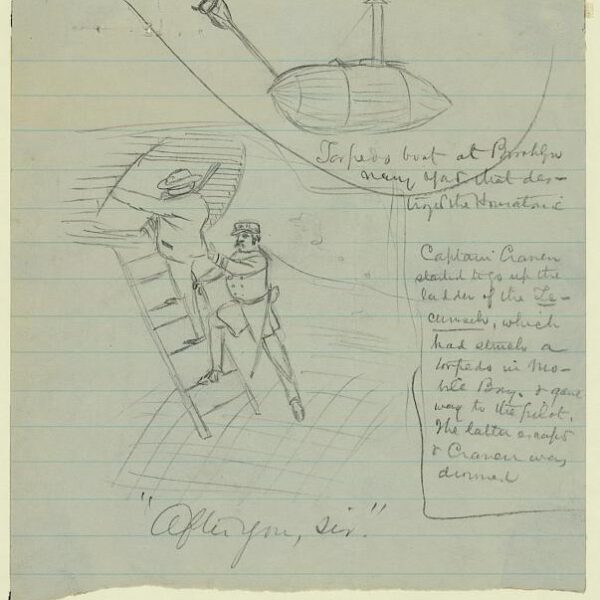

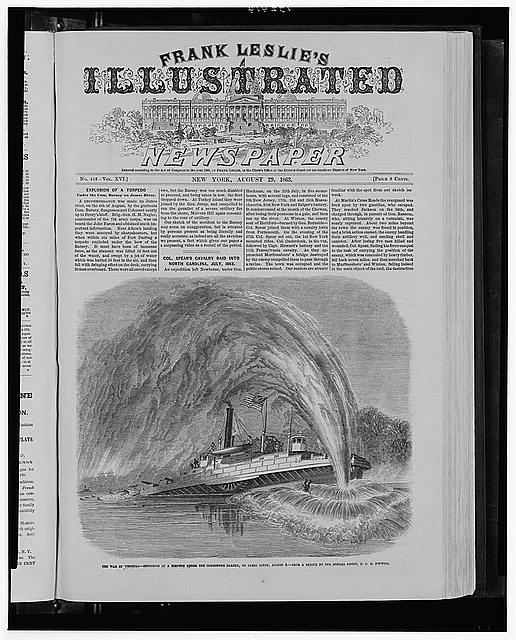

Back in Mobile Bay in April 1865, Eli Robinson, a 24-year-old African American who was over six feet tall and “stout in proportion,” was a “landsman” in the navy. Nevertheless, he was serving aboard the Rodolph, a stern-wheel steamer, towing a barge toward the sunken Milwaukee and Osage. As the Rodolph neared the wreckage site, a tremendous explosion ripped through the aft part of the steamer. Harper’s Weekly, while devoting most of its April 29, 1865, issue to President Lincoln’s assassination, used a page to report on Mobile that included illustrations of mines and the steamer’s explosion.7

The blast left three dead and 11 others suffering severe wounds, most commonly around the knee, and at least one suffering from a “concussion of brain,” injuries similar to those from today’s IEDs. Robinson, described as having a “strong constitution,” dislocated his left knee and broke his left leg. Surgeons at Mobile soon transferred him to Pensacola. There, doctors using their fingers to probe around the broken bones and fragments discovered more extensive injuries above his ankle and decided to amputate.8

For two weeks, Robinson appeared to be recovering when he suddenly complained about headaches and nausea and then chills and high fevers. Surgeons made an incision in the stump and pus ran out, indicating blood poisoning. Realizing he needed more care than quinine, Robinson was moved to New York, arriving there on June 15. “He was discharged from service November 24, 1865, with a good stump, being able to walk easily and well on an artificial limb and suffering no weakness of the knee.” Robinson was a fortunate man. Fifteen years later, he was awarded a veteran’s pension, and he reported the stump remained in “good and healthy condition.” His case is one of the few mine injuries documented in the medical/surgical history of the Civil War and the only one preserved at National Museum of Health and Medicine, now in Silver Spring, Maryland.9

Back in Pensacola, Passed Assistant Surgeon J.R. Tryon, USN, sent Robinson’s amputated bones to the Army Museum of Medicine, established in 1862 by the service’s surgeon general to preserve medical lessons learned in the war. The museum moved from Washington’s Walter Reed Army Medical Center as part of the Base Realignment and Closure Act. The bones are in storage, but may again be on display in a year.10

Jan Herman also noted that, “The treatment of choice for the Civil War mine-induced injuries would have been the treatment of choice for other wounds – removing splinters and fragments and amputating unsalvageable limbs.” That was the Civil War’s “aggressive treatment” in confronting blast wounds. Today’s soldiers and marines use sniffer dogs, aerial and ground unmanned vehicles, radio jammers and special software to calculate likely IED locations and destroy them. Moreover, they are all trained in combat medicine. Military surgeons know “Modern [IED] injuries are successfully treated using a specific protocol of treatments that ranges from surgical débridement and leaving all wounds open to early fracture stabilization, administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics, and rapid evacuation to higher levels of care.”11

In his time, Eli Robinson proved that.

John Grady, a former editor of Navy Times and retired director of communications for the Association of the United States Army, is completing a biography of Matthew Fontaine Maury. He is a contributor to the Navy’s Civil War Sesquicentennial blog, the New York Times‘ Disunion online series, and the Army Historical Foundation’s On Point: The Journal of Army History.

1Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, Navy, Ser. 1, Vol. 22, pp. 70-78. “The Siege of Mobile,” Harper’s Weekly, April 29, 1865.

2 Ibid.

3 E-mail interview by author with Jan Herman, senior historian, Navy Medical Department, Nov. 30, 2011.

4 John Grady, “‘Infernal Machines’: Mine Warfare in the Civil War,” On Point, The Journal of Army History, Fall 2012, Vol. 18, No. 2, pp. 6-14; Sherman to Steadman, Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, Vol. 38, Part 4, p. 579. Grady, “Infernal Machines”; Dr. Charles A. Lee, Dr. Isaac Hays, ed., Transactions of State Medical Societies, The American Journal of the Medical Sciences, Philadelphia, Blanchard and Lea, 1862, p. 411.

5 Dr. S.W. Gross, “Torpedo Wounds,” The American Journal of the Medical Sciences, Vol. 52, 1866, pp. 370-372. Col. Norwood P. Hollowell, “The Negro as a Soldier in the War of the Rebellion,” Read Jan. 5, 1892, Paper of the Military History Society of Massachusetts, Vol. 13, Cadet Armory, Boston, 1913. “Operations around Charleston,” Fraser’s Magazine for Town and Country, Vol. 74, July to December, 1866, p. 110. “Details of Operations.; The Storming of fort Sumter …” New York Times, Sept. 17, 1863; Gross, “Torpedo Wounds.”

6 Gross, “Torpedo Wounds.”

7 Intermediary Amputations of the Leg, Case 775, Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, Vol. 12, p. 529; Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, Navy, Ser. 1, Vol. 22, pp. 70-78.

8 Intermediary Amputations of the Leg, Case 775, Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, Vol. 12, p. 529.

9 Ibid.

10 Telephone interview by author with museum’s Public Affairs Office July 9, 2012.

11 E-mail interview by author with Jan Herman, senior historian, Navy Medical Department, Nov. 30, 2011; “A Brief Background on Combat Injuries,” 2007 Annual meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, available at www.aaos.org/news/bulletin/marapr07/research2.asp.

Photo Credit: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs, www.loc.gov