Library of Congress

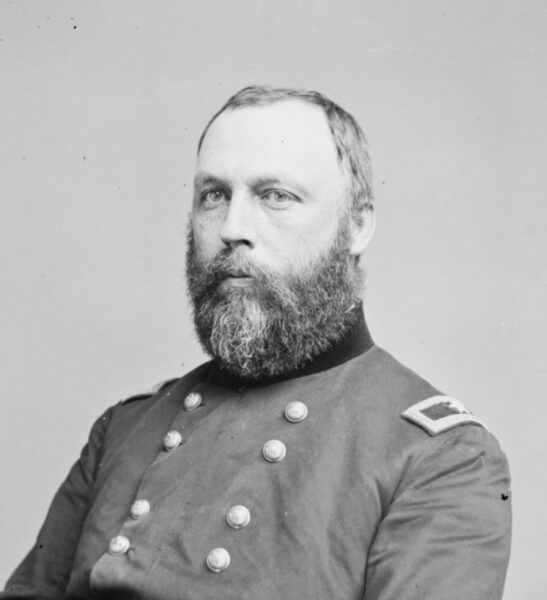

Library of CongressSurgeon General of the U.S. Army William A. Hammond

Medicine during the Civil War is often thought of as having been dangerous and backward. Surgeon General of the U.S. Army William A. Hammond, who served from 1861-1863, is supposed to have once described the war as being fought at the “the end of the medical Middle Ages.” By this, Hammond explained that the war occurred in an era with relatively limited medical knowledge, which meant that physicians did more harm than good.

It is true that wartime hospitals were often unhealthy, terrifying places that soldiers tried to avoid. Soldiers died of malaria and infections like gangrene that are treatable today. Roughly two-thirds of the Civil War’s 750,000 deaths were from disease.

But if we focus only on gruesome amputations and deadly diseases, we miss half the story of Civil War medicine. Exploring the use of drugs such as the antimalarial quinine and the painkiller morphine highlights how much medicine advanced during the war.

Opiates and quinine became ubiquitous during the war, saving countless lives and easing untold suffering. A Confederate medical handbook described painkilling opium as an “indispensable drug on the battlefield—important to the surgeon as gunpowder to the ordnance.” The same held true for quinine. The war’s toll of death and suffering would have been even worse without these drugs.

Quinine was among the most important therapeutic agents available to military surgeons. Produced from the bark of the South American cinchona tree, quinine was used to treat malaria and other fevers.

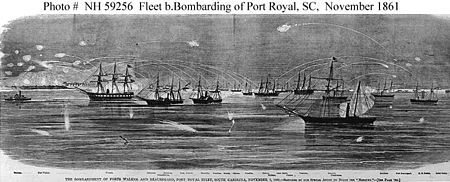

Diseases like malaria constituted a kind of invisible “third army” that could derail campaigns. In the spring of 1862, Union general George B. McClellan’s attempt to take Richmond fell apart after his Army of the Potomac was devastated by outbreaks of malaria, typhus, and dysentery, reducing troop strength by a third. The swampy landscape of the Chickahominy River and similar locales in the South were breeding grounds for mosquitoes carrying malaria. Southerners who had developed some level of immunity expected that unseasoned northern invaders would sicken and die by the thousands.

The federal government created pharmaceutical laboratories in New York City and Philadelphia to mass manufacture drugs like quinine and morphine, ensuring that Union surgeons had ample access to their use. Historian Margaret Humphreys has found that that malaria mortality among white Union soldiers was much lower than among Confederates, depending upon the region.

In contrast, Confederates struggled to manufacture either drug and shortages hurt the Confederacy’s ability to wage war. One Charleston surgeon reported having just 12 ounces of quinine to dole out in the first half of 1864, when a small hospital ideally would have had 160 to 200 ounces of quinine on hand for the same period. Blockade runners made huge profits smuggling quinine and morphine, but shortages worsened over time. Confederate doctors tried to use local plants, like dogwood bark, as substitutes for quinine without much success (although scientists have recently become interested in such substitutes). When the Confederate hospital system finally collapsed in 1865, drugs were practically impossible to find.

If quinine was crucial for the Union’s victory over both the Confederacy and the “third army” of disease, opiates were equally essential remedies for the ailments of war such as pain and diarrhea. Many Americans by this time already considered opiates to be divine gifts that made a dreary world palatable by easing pain and suffering. Analgesics like aspirin, ibuprofen, or acemetacin all developed decades later.

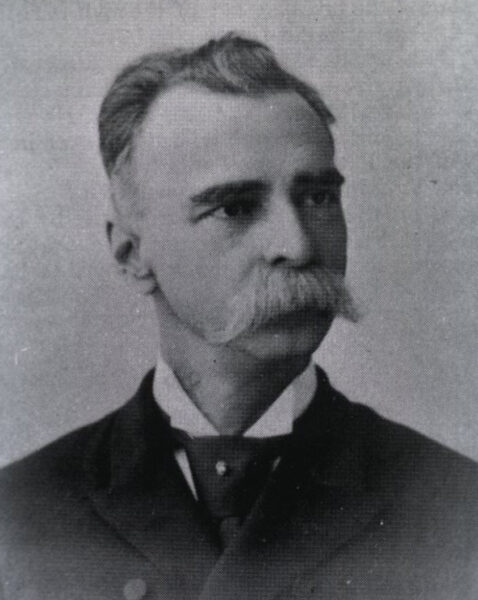

Find a Grave

Find a GravePhysician Félix Formento Jr. in a postwar photo

Physician Félix Formento Jr. served at the Louisiana Hospital in Richmond and wrote a medical handbook based on his experience. He instructed Confederate surgeons to use opiates as first-line drugs for everything from dysentery, diarrhea, and typhus to painful gunshot wounds. “Opium should be given freely and frequently” to soldiers with chest wounds because “it quiets the cough, diminishes respiration, allays pain, and by its antiphlogistic properties operates directly against inflammation.” Formento described treating one grievously wounded soldier’s perforated liver, which was leaking blood and bile, with ice, cloth dressings, and a grain of oral opium every four hours. Gangrene often attended gunshot wounds and, as with treating trauma wounds, American doctors had little experience treating this ghastly infection before the Civil War. Formento took great pains to explain how to treat gangrene, instructing readers that “opium in repeated doses is of great service to allay the pain, irritability and sleeplessness” stemming from the frightful condition that seemed to spread mysteriously in hospital wards.1

Civil War surgeons mostly followed these recommendations, administering opiates “freely and frequently” to ailing soldiers. Diarrhea and dysentery were perhaps the most common health complaints of the war, and the antidiarrheal properties of opium, morphine, and laudanum made these medicines invaluable. Caleb Dorsey Baer, a young Confederate, suffered from a particularly severe bout of diarrhea in 1861. “Have been very unwell all day,” he wrote, “having frequent discharges of blood and mucus from my bowels, and intense tenesmus.” Baer “could not obtain any ease until I took sufficient morphia to narcotise me almost,” so he took “pretty full” doses of morphine for two weeks until the “derangement” of his bowels ceased.2 Peter W. Homer, a cavalryman from New Jersey, endured “exhausting diarrhea, from ten to twelve thin watery evacuations daily,” off and on for three months in early 1863.3 It was the surgeons’ job to keep soldiers like Baer and Homer off the sick roll by managing symptoms with drugs, diet, and rest.

If armies relied heavily on opiates, their shortage could be debilitating. The opium needed to manufacture morphine was imported from Asia, and although blockade runners carried on a brisk trade, supplies often ran low in the Confederacy.4 During the 1863 siege of Vicksburg, John C. Pemberton’s Confederate army desperately needed morphine, so troopers crossed the Mississippi River 80 miles north at Greenville in a desperate search for the drug.5

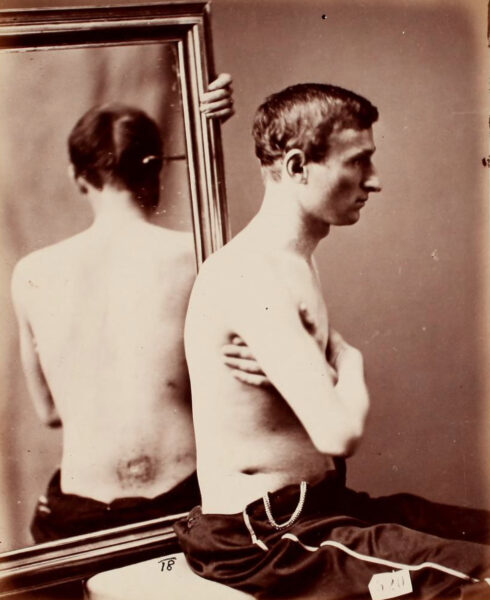

Photographs of Surgical Cases and Specimens, Vol. 2 (1865)

Photographs of Surgical Cases and Specimens, Vol. 2 (1865)Photograph exhibiting what remained of Lieutenant G.P. Deichler’s gunshot wound after it healed. Like many wounded Civil War soldiers, he received hypodermic morphine injections for pain over an extended period of time.

Where opiates flowed freely, surgeons developed innovative ways to use them. The Civil War helped popularize the hypodermic syringe, recently invented in Europe but largely unfamiliar to Americans before the war. Combat injuries made immediate pain relief essential, but oral opiates were slow to act. Union surgeons turned to hypodermic morphine, which brought relief nearly instantaneously. G.P. Deichler, a young lieutenant in the 69th Pennsylvania Infantry, was shot in the hip at Hatcher’s Run, Virginia, in March 1865—among the last casualties of the war. The bullet tore its way through Deichler’s colon, making a large exit wound in the small of his back. The ball missed his spinal cord by centimeters; immobilized and oozing feces through the hole in his back, Deichler seemed doomed. Surgeons at Armory Square Hospital in Washington, D.C., dosed the lieutenant with a quarter grain of morphine every two hours for 27 days. In a morphine haze, Deichler hung between life and death. He miraculously got better in late April. Astonished surgeons made a photograph that eventually became part of the collection at the newly founded Army Medical Museum.

Despite their importance and utility, opiates are often criticized in medical histories of the war. It is true that surgeons’ usage was sometimes scattershot and that opiates could lead to accidental overdoses.

Many soldiers also came home from the war addicted to morphine and opium. Given the stigmatized nature of addiction, many tried to keep it secret. So-called “slavery” to opiates presented serious health and social challenges in their postwar lives. Although addicted men often traced their condition back to war-related medical care, society largely blamed them. The Gilded Age that followed the war witnessed an exponential surge in opiate use among a broad swathe of Americans, some of it traceable to aftereffects of the Civil War.

Yet the innovative use of drugs challenges myths about Civil War medicine and illustrates how the war spurred advances in medicine. The history of the war cannot be fully understood without including morphine and quinine, which enabled armies to hold their own against pain and sickness. The acute health needs of both armies spurred therapeutic innovations that profoundly shaped American medicine for decades. Medicine today would be unrecognizable without hypodermic syringes or quinine, still widely used in parts of the world where malaria remains endemic.

Drugs, surgeries, treatments, hospitals—all of these remind us that the Civil War’s bloody military story includes chapters mixing medical innovation with human sympathy.

Jonathan S. Jones is an assistant professor of history at James Madison University. His research explores the medical and social legacies of the Civil War among veterans, their families, and doctors. His book Opium Slavery: Civil War Veterans and Opiate Addiction is forthcoming from UNC Press.

Notes

1. Félix Formento Jr., Notes and Observations on Army Surgery (1863), “Give opium freely and frequently,” 35; Gunshot wound to liver, 30–33; “Opium in repeated doses” in ibid., 49; dysentery and diarrhea, 12–13; typhoid, 15; chest wounds, 29: gunshot wound to liver, 30–33: gangrene, 49; erysipelas, 57. On Gangrene, see Shauna Devine, Learning from the Wounded (2014), chapter 3.

2. Quoted in F. Terry Hambrecht and Terry Reimer, eds., Caleb Dorsey Baer: Frederick, Maryland’s Confederate Surgeon (2013), 100, 130. Tenesmus is the inability to pass stool despite the feeling of urgent need.

3. Quoted in George Rable, Fredericksburg, Fredericksburg! (2002), 105.

4. James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom (1988), 378–382.

5. Frances Miller, ed., The Photographic History of The Civil War in Ten Volumes (1911), Vol. 7, 240.

Related topics: medical care, social-offer