The contruction of my historiographical self began on a rainy afternoon in fifth grade. There was no chance for outdoor romping, or venturing through the deluge to a friend’s house to play after school. Instead, I ran to my room with a library copy of a gray-bound book for young readers, MacKinlay Kantor’s Gettysburg (1952). I plopped onto my bed and soon lost myself in a story that, I can see now, directed my young spirit in a way that would shape my life.

The contruction of my historiographical self began on a rainy afternoon in fifth grade. There was no chance for outdoor romping, or venturing through the deluge to a friend’s house to play after school. Instead, I ran to my room with a library copy of a gray-bound book for young readers, MacKinlay Kantor’s Gettysburg (1952). I plopped onto my bed and soon lost myself in a story that, I can see now, directed my young spirit in a way that would shape my life.

I was no nerd; I still played hard when the sun shone. But this boy developed a love for rainy days and books about history. On rainy days I cavorted not with my neighborhood mates but with Daniel Boone in the Wilderness, or trailed Robert E. Lee and Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox, or walked with Richard Tregaskis at Guadalcanal—traveled anywhere the Landmark Books Series for kids would take me. I came to lament my mom’s calls to dinner, but I returned to my stories as soon as the dishes were done. I have a memory that I read Gettysburg in a single rainy afternoon. I see now that wasn’t possible—it’s 162 pages—but the experience felt so intense, it seems it could not have been otherwise.

Kantor’s is a good story, told vividly (he went on to win the Pulitzer Prize for his 1955 novel, Andersonville). His Gettysburg has all sorts of shortcomings that would furrow a historian’s brow today. It is history lite—pure, selective storytelling—full of anecdotes, memorable characters (John Burns!), and even humor. The kinetic forces that mangledsoldiers and scarred the battle- field are present only by implication—“Cannons had roared, rifles had jabbered,” Kantor wrote of the Pickett-Pettigrew assault. But he wrote with empathy, and told stories of civilians, the wounded, their caregivers. In my life, I remember the experience of reading few books, but I remember Gettysburg explicitly.

(A sorry aside: The summer following fifth grade, my parents took me to Gettysburg. I assumed their expectation was that the family’s newfound expert would give the tour—no licensed battlefield guide needed with me around. Armed only with what I had read by Kantor and the memorable diagrammatic maps from the Golden Book of the Civil War [1961], I stepped out with authority, promptly lost any sense of direction, and crumpled under the pressure. I slunk into the back seat of the car defeated and embarrassed.)

Here’s the funny thing about Kantor and my initiation into Civil War history: When I recently revisited Gettysburg, it struck me that Kantor’s history for youngsters was very much like the tours I gave when I started working at Manassas National Battlefield Park for the National Park Service (NPS) in the early 1980s. Humor to loosen folks up, lots of vivid action (largely absent the kinetic realities), and then the heartstrings. Empathy, often evoking tears from the audience, was the surest sign of interpreter success, ’80s style.

Mind you, none of this was bad. I was and am proud of the work I and my colleagues did in the field with thousands of visitors. I hope our work fired some young minds, as Kantor did mine. But, as history shows us, it wasn’t enough.

In 1991, Edward Linenthal’s book Sacred Ground: Americans and Their Battlefields appeared. Linenthal asked us to see battlefields not merely as settings for an event long past, but as places made dynamic by the efforts of successive generations to remember and commemorate, often in competing and almost always in selective ways. He forced me, and many others in the NPS, to see ourselves as agents of remembrance. Staff at battle sites make choices every day about what we ask visitors to remember—in our tours, films, and exhibits. Linenthal emphasized that we did not work on neutral ground, but rather on landscapes shaped by more than a century of commemorative efforts by groups with distinct interests. We could not be masters of a singular, unquestioned memory of the past. Linenthal forced us to see that our work was part of a generations-old effort by Americans to understand their past in a way that comported with their present interests or worldview. To me, it became obvious that no one working in the field of public history at a Civil War site could do so effectively without understanding the societal forces that have and will shape that work. Sacred Ground was essential.

In 1991, Edward Linenthal’s book Sacred Ground: Americans and Their Battlefields appeared. Linenthal asked us to see battlefields not merely as settings for an event long past, but as places made dynamic by the efforts of successive generations to remember and commemorate, often in competing and almost always in selective ways. He forced me, and many others in the NPS, to see ourselves as agents of remembrance. Staff at battle sites make choices every day about what we ask visitors to remember—in our tours, films, and exhibits. Linenthal emphasized that we did not work on neutral ground, but rather on landscapes shaped by more than a century of commemorative efforts by groups with distinct interests. We could not be masters of a singular, unquestioned memory of the past. Linenthal forced us to see that our work was part of a generations-old effort by Americans to understand their past in a way that comported with their present interests or worldview. To me, it became obvious that no one working in the field of public history at a Civil War site could do so effectively without understanding the societal forces that have and will shape that work. Sacred Ground was essential.

Then came David Blight’s Race and Reunion (1998) and Karen Cox’s Dixie’s Daughters (2003). Blight emphasized the forces that helped shape how we remember the Civil War, and they were not pretty. Most good works of history bend the needle of knowledge and understanding; Race and Reunion commenced an academic tide and public discussion that continues today. Excellent historians have challenged or offered modifications to some of Blight’s underlying arguments, but Race and Reunion remains a book that everyone who works at a site related to the Civil War should read.

Cox’s Dixie’s Daughters is a nearly forensic analysis of the efforts of the United Daughters of the Confederacy to shape Americans’ perceptions of the antebellum South, the Confederacy, Confederate soldiers, and the causes for which they fought. The popular understanding of “revisionist history” is a history purposely manipulated toward a political or social end. Cox demonstrated that few things match the United Daughters of the Confederacy’s successful attempts to revise and shape Americans’ perceptions of their Civil War history—perceptions that often doggedly survive and thrive in our culture as simplicities that are either purposefully incomplete or flat wrong. I was prepared when I read Dixie’s Daughters, but still found it stunning.

If Linenthal deals with the evolution and challenges of interpretation and commemoration at Civil War sites, Blight and Cox remind us that remembering entails a whole lot of forgetting, and that forgetting can inflict enduring harm. That thought did much to shape the last 25 years of my NPS career.

As for writing history, when I attempted a 200-level writing class in college, I was turned down based on my writing sample. I had a lot of work to do, and finding a voice took time and a lot of inspiration and advice from others. Stephen Sears’ Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam (1983) showed me that excellent prose and thoughtful history are the ingredients for a memorable book. Though it has fallen out of some favor, it’s a beautifully crafted volume that inspired me as I wrote my book on Second Manassas, Return to Bull Run (1993).

As for writing history, when I attempted a 200-level writing class in college, I was turned down based on my writing sample. I had a lot of work to do, and finding a voice took time and a lot of inspiration and advice from others. Stephen Sears’ Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam (1983) showed me that excellent prose and thoughtful history are the ingredients for a memorable book. Though it has fallen out of some favor, it’s a beautifully crafted volume that inspired me as I wrote my book on Second Manassas, Return to Bull Run (1993).

When I got stuck in my writing, I looked for written voices to unstick mine. Say what you will about Douglas Southall Freeman and his Lee’s Lieutenants (1942), but the man could write. His attention to the rhythm of words is unmatched and, problems of history aside, his trilogy was always a joy to read. (One thing about Lee’s Lieutenants I discovered while working for the NPS: Most historians loved the trilogy, but they almost always claimed that the chapter relating to the site they worked at was the worst in the book or significantly flawed.)

I often turned to the prose in two primary sources to remedy my addled mind. Almost any page of the Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (1953) will do for literary motivation. His simple directness and phrasing are on another level. He appeals to my aspirational core. And ever since I came across John Washington’s Memorys of the Past, I regularly turn to this memoir (published twice in the 2000s) for inspiration. It would fail anyone’s measure of fine composition, but the narrative of this once-enslaved man from Fredericksburg is perhaps the greatest chronicle I have read of a life striving toward freedom. If your spirit or your writing needs a dose of hope and determination, read Washington.

These days, when my writer’s brain fails me, I routinely reach for three volumes to get me going again. Blight’s 2018 biography, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom, is masterfully written—a worthy and thoughtful chronicling of a historic life. In Belligerent Muse (2017), Stephen Cushman considers the best writers of the Civil War era, and pulls it off because he is one of the best writers of our era. Caroline Janney’s 2021 Ends of War: The Unfinished Fight of Lee’s Army after Appomattox is gracefully written and powerfully argued (an uncommon combination). She helps me make sure I connect small details with big ideas.

So it is that I constantly read essays and books that make me think and rethink how I approach the practice of history. The project begun on a rainy afternoon in fifth grade continues.

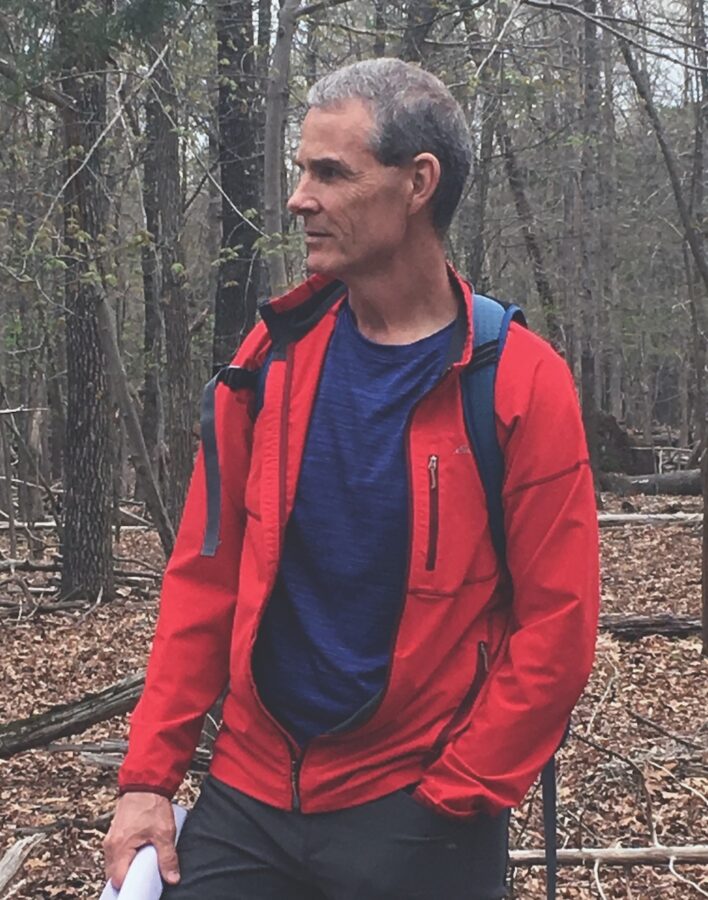

JOHN HENNESSY RECENTLY RETIRED AS THE CHIEF HISTORIAN AT FREDERICKSBURG AND SPOTSYLVANIA NATIONAL MILITARY PARK, WHERE HE WORKED FOR THE FINAL 26 YEARS OF HIS NPS CAREER. HE IS THE AUTHOR OF FOUR BOOKS, MOST NOTABLY RETURN TO BULL RUN: THE CAMPAIGN AND BATTLE OF SECOND MANASSAS (SIMON & SCHUSTER, 1993).

This article appeared in the Fall 2023 issue of The Civil War Monitor.