No event in American history has inspired more imaginative writing than the Civil War. Authors have made the struggle the subject of thousands of rhymes, songs, poems, short stories, plays, radio shows, and screenplays.

In particular, readers and writers have gravitated toward Civil War novels. Well over 1,000 such novels have seen print since 1862, with about 200 published since the turn of the new millennium. The sheer volume of such writing can pose a challenge to readers today. Which texts might one turn to for a combination of artistry, historical in- sight, humanity, and narrative? The short list below is necessarily incomplete, leaving out many superb novels. But each book stands as an artistic success, and the selections together illustrate the central theme of Civil War literature—individual participation in the nation’s defining conflict.

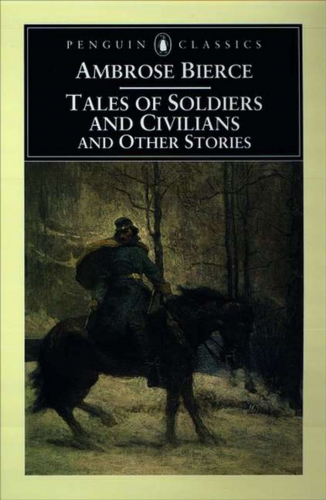

Tales of Soldiers and Civilians (1892) by Ambrose Bierce

Although thousands of Civil War soldiers penned memoirs of their experiences in uniform, relatively few authored fiction about the war. Of those who did, the greatest was Ambrose Bierce, a veteran of the 9th Indiana Infantry. In 1892, Bierce published the dark masterpiece Tales of Soldiers and Civilians. While technically a collection of 19 short stories, the contents offer the thematic cohesion of a single narrative. Bierce depicts soldiers whose commitment to duty, unit, and protocol conflicts with the non-military qualities that their training was meant to suppress. The stories include moments of moving heroism and sacrifice, but more often show the personal and familial suffering required of Americans caught up in a vast civil war. Readers will find these ironic stories spiked with cowardice, hubris, jealously, and desperation, all vividly present in Bierce’s most famous story, “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge.”

The Red Badge of Courage (1895) by Stephen Crane

Born in 1871, Stephen Crane grew up at a time when the memoirs of Civil War veterans dominated the literary market. The young writer found these stilted works frustrating, once telling a friend: “I wonder that some of these fellows don’t tell how they felt in those scraps! They spout eternally of what they did, but they are as emotionless as rocks!” In publishing The Red Badge of Courage, Crane gave the reading public what soldiers’ slow and sanitized memoirs did not: a portrait of Civil War combat replete with noise, fear, rage, speed, adrenaline, sweat, and blood. For the first time, many readers believed, they could experience the nation’s greatest struggle on an emotional, visceral level. The novel irked some veterans, who saw it as a kind of literary trespassing, but the public made the book a bestseller. Ambrose Bierce conceded that while Crane had not experienced battle himself, his imagination had produced an authentic portrait of war: “This young man has the power to feel. He is drenched in blood. Most beginners who deal with this subject spatter them- selves merely with ink.”

Gone with the Wind (1936) by Margaret Mitchell

Gone with the Wind (1936) by Margaret Mitchell

Far more than a historical romance, Margaret Mitchell’s colossal bestseller offers one of the finest portraits of the southern home front during the Civil War. In fact, Gone with the Wind interprets Reconstruction as part of that same struggle, detailing the poverty, toil, and disease facing a limping South during the years after 1865. While undeniably racist at times, the novel is progressive in its portrait of white southern women, whose personal and family perseverance demanded respect. At the end of the novel, a nostalgic Scarlett O’Hara looks back on what she accomplished during those tumultuous years as a wife, widow, mother, landowner, farmer, businesswoman, and survivor. The novel then claims for Scarlett an identity too often denied southern women who lived through the war: “They were veterans. She was a veteran too.”

The Unvanquished (1938) by William Faulkner

William Faulkner peoples The Unvanquished with civilians on the Mississippi home front—especially children, old women, and slaves. The Nobel Prize-winning writer found these figures far more compelling than the soldiers and belles of most Lost Cause narratives. Indeed, in southern fiction the term “unvanquished” would typically refer to white Confederates who, though defeated in war, refused to be broken. Faulkner expands the term to include the African-American residents of his fictional Yoknapatawpha County, a people whose mass exodus for the Union lines stands as one of the most memorable scenes in all of Civil War literature. No matter what trials and reverses await these men and women, the novel celebrates their timeless, universal impulse to “sail irrevocably on and either find land or plunge over the world’s roaring rim.”

The Killer Angels (1974) by Michael Shaara

Well tuned to late-20th-century sensibilities, Michael Shaara’s The Killer Angels stands as one of the most beloved of Civil War novels. Shaara represents Gettysburg as the ultimate clash between Old World aristocracy and American individualism. Only through northern victory, the novel suggests, could the nation destroy an oppressive class system that threatened to enslave all Americans, regardless of race. One might expect southern partisans to chafe under this narrative. Yet because Shaara portrays the southern high command with respect, and celebrates shared American ideals, few readers have found reason to complain. It is worth noting that Shaara did much to elevate the popular reputations of both James Longstreet and Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain—further evidence of fiction’s role in shaping historical memory.

The Judas Field (2006) By Howard Bahr

Haunting and unforgettable, The Judas Field applies what we have learned about post-traumatic stress disorder to the lives of Confederate veterans. Howard Bahr, himself a Vietnam veteran, takes readers back and forth between the Civil War and the postwar lives of soldiers—men whose psychological wounds lead to nightmares, substance abuse, and social isolation. When encountering Bahr’s traumatized characters, we cannot help but revise our thinking about the old Yankees and Confederates pictured in photographs of battlefield reunions. How many of those men led lives of quiet desperation, proud of their service but too badly scarred to ever truly return to civilian life? The Judas Field reminds us that the human toll of the war extended far beyond the more than 600,000 Americans who perished between 1861 and 1865.

Further Reading

Many other Civil War novels deserve a wider readership. In 1867, Union veteran John W. De Forest published Miss Ravenel’s Conversion from Secession to Loyalty, a book whose lighthearted title belies a harrowing study of love and war. The Long Roll (1911), by the historical novelist Mary Johnston, arrived on the doorstep of World War I. This impressive work is equal parts Lost Cause narrative and anti-war manifesto. Two years before The Unvanquished, William Faulkner published Absalom, Absalom! (1936), offering readers a challenging, brilliant portrait of race relations and the fall of a southern family. One of Faulkner’s literary proteges, Shelby Foote, authored the battlefield novel Shiloh in 1952. Exploring the famous battle from various perspectives, northern and southern, the novel anticipates the structure of The Killer Angels. Of 21st-century works, few rival The March (2005) by E.L. Doctorow. In its pages, humanity is swept along by historical forces beyond the control of even the most powerful of generals and politicians. Still more Civil War novels will be published this year and in the decades to come—new entries in a thriving genre concerned with race, region, and national identity.

Craig A. Warren is an associate professor of English at Penn State Erie, the Behrend College. He is the author of Scars to Prove It: The Civil War Soldier and American Fiction (2009) and the editor of the Ambrose Bierce Project (ambrosebierce.org).

This article appeared in the Spring 2013 issue of The Civil War Monitor.