Bruce Catton

When I was 12 I found a mass market paperback of Bruce Catton’s A Stillness at Appomattox, and it yanked me so deep into the world of the Civil War that I never got out—or ever wanted to. In this I was far from alone. David Blight, author of several prize- winning books on the Civil War, discovered Catton at about the same age. “I used to pray for rain on my summer jobs so that I could read Stillness, Hallowed Ground, or Terrible Swift Sword,” he remembered. “Catton’s unsurpassed storytelling about the Civil War had much to do with my choice to become a historian.”[1] Pulitzer Prize-winning historian David McCullough bought a copy of A Stillness at Appomattox as a college senior “and looking back,” he wrote, “I think it changed my life. I didn’t know that then, naturally. All I knew was that I had found in that book a kind of splendor I had not experienced before, and it started me on a new path.”[2]

Tens of thousands of other readers have discovered that same splendor in Catton’s work.

For some, it placed them on the path to becoming historians. For many more, it simply drew them into a lifelong love of reading about the war. Either way, few would contest that Catton ranks among the foremost bards of the American Iliad.

Bruce Catton was almost an exact contemporary of Shelby Foote, the bard I profiled in my last column. Foote discovered early in life that he wanted to be a novelist. At 33 he published his first novel; by the time he was 47 he had published three more novels and was two-thirds of the way through his magisterial trilogy The Civil War: A Narrative, whose flair derives precisely from Foote’s lifetime spent carefully honing his literary craft. Catton’s own craft emerged in a very different way. Born in rural Michigan in 1899, he became a reporter and for two decades worked for a number of newspapers. By 1939 he was in Washington, writing a syndicated newspaper column. There he accepted a position as director of information for the War Production Board. This resulted in a book of observations entitled The War Lords of Washington (1948). Although only a minor success, it emboldened him to begin writing books full-time. He was then 49—a rather advanced age at which to discover one’s true vocation.

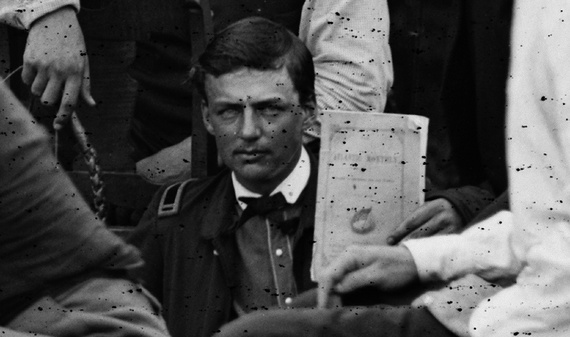

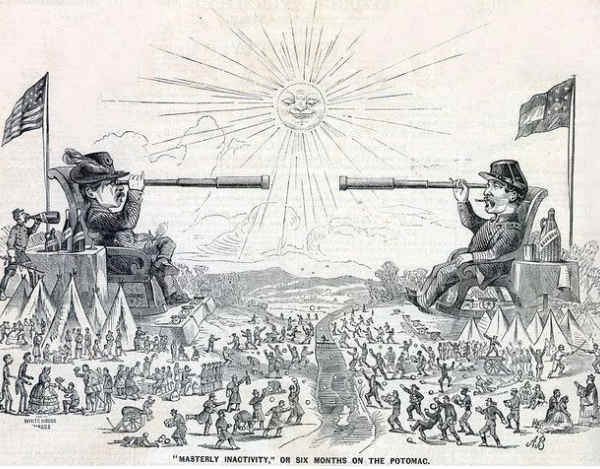

Catton’s first effort, Mr. Lincoln’s Army, appeared in 1951 and became the first volume in a trilogy about the Army of the Potomac. It covered Major General George B. McClellan’s tenure in command—it might more aptly have been called General McClellan’s Army. But neither title was quite applicable, because the book focused on the common soldier as much as their commanders. Nor did it delve very deeply into the details of the army’s battles, certainly not with the play-by-play approach that characterizes so many battle books. Catton’s own approach was more impressionistic. He sought to imagine what it was like to be a Civil War soldier, a fascination that tracked back to his childhood growing up among Union veterans in his boyhood town of Benzonia, Michigan.

Mr. Lincoln’s Army ended with the Battle of Antietam. Catton followed it up with Glory Road (1952), which covered the Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, and Gettysburg campaigns. Each book sold only about 2,000 copies, and it took some effort for Catton to persuade his publisher, Doubleday, to put out the third volume in the trilogy. Happily for writer and publisher, A Stillness at Appomattox (1953) brought him both a wide readership and enormous critical acclaim, including the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize for Nonfiction.

In the years that followed, Catton wrote more than a dozen other books on the war, including a three-volume Centennial History of the Civil War (1961–1965), a two-volume biography of Ulysses S. Grant’s Civil War career (1960, 1969), and two histories for young readers: The American Heritage Picture History of the Civil War (1960), and The Battle of Gettysburg (1963). But it was not Catton’s impressive productivity that brought him fame. Rather, it was his ability to convey what he called “an emotional understanding” of the conflict. Readers, he maintained, were not particularly interested in the intricate details of, say, the Battle of Gettysburg; “yet the man who can make us feel and see that stupendous fight will get our attention because he helps us to comprehend the enormous intangibles which were involved there. These intangibles … reveal themselves most readily to the person whose feelings and imagination have been touched…. They come in moments of insight born of emotional understanding. There are many things about the Civil War which no historian can actually prove; he can only show them.”[3]

No one excelled at showing the war more than Catton, and for at least three reasons. First, he simply knew a great deal about the conflict, particularly the life of the ordinary soldier, some of which he learned from the veterans whose stories he heard as a child, but much of it gleaned from a voracious reading of Civil War regimental histories—homespun books written mainly by and for the soldiers themselves, but which offered an almost palpable feeling for what life was like in camp, on the march, and on the battlefield.

Second, Catton wrote in a style that often verged on poetry. Here, for instance, he describes the moment when McClellan rejoined the soldiers of the Army of the Potomac after their drubbing under a lesser commander, Major General John Pope. “As the sun went down over the Virginia hills [McClellan rode] to the sound of men who cheered as if they had touched the shores of dream-come-true…. He cantered down the dusty roads and met the heads of his retreating columns, and cried words of encouragement and swung his little cap, and he gave the beaten men what no other man alive could have given them—enthusiasm, confidence, an exultant and unreasoning feeling that the time of troubles was over and everything would be all right now.”[4]

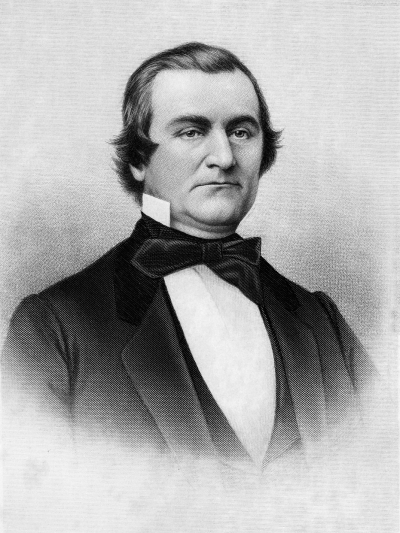

William Lowndes Yancey

As the vignette reveals, Catton saw history not as a matter of vast impersonal forces but rather of individuals caught up in experiences larger than themselves, and he almost always placed individuals in the foreground of his narratives. Most histories of the election of 1860, for example, begin with a general overview of the political crisis of the 1850s that made secession a likely outcome. But Catton zeroed in on a specific figure, William Lowndes Yancey, foremost of the southern “fire-eaters” who would bring about disunion. The first volume of his Centennial History begins, “Mr. Yancey could usually be found at the Charleston Hotel, where the anti-Douglas forces were gathering, and a Northerner who went around to have a look at him reported that he was quiet and mild-mannered. No one, seeing Yancey in a room full of politicians, would pick him out as the one most likely to pull the cotton states into a revolution. He was compact and muscular, ‘with a square-built head and face, and eye full of expression,’ a famous orator who scorned the usual tricks of oratory and spoke in an easy conversational style.”[5] One almost has the sense of walking into the hotel lobby and encountering Yancey first-hand. From there, Catton’s narrative opened outward into a lucid account of the intricate machinations of the 1860 election—as sure-footed and competent as any professional historian might write—but never straying far from the experiences and observations of individuals.

“History after all is the story of people,” Catton declared, “a statement that might seem too obvious to be worth making, if it were not for the fact that history so often is presented in terms of vast incomprehensible forces moving far under the surface, carrying human beings along, helpless, and making them conform to a pattern whose true shape they never see. The pattern does exist, often enough, and it is important to trace it. Yet it is good to remember that it is the people who make the pattern, and not the other way around.”[6]

The pattern, it must be said, usually excluded the moral stakes of the conflict, which Catton tended to finesse. Although he often focused on Union soldiers, wrote sympathetically about African-American slaves, and viewed the destruction of slavery as the birth of a new freedom, this somehow did not translate into criticism of the Confederate cause. Confederate apologists created and exploited the myth of the Lost Cause, for example, as a way to deny that the southern states had seceded in order to protect slavery and had spent four years desperately fighting to hold 3.5 million Americans in bondage. Yet Catton argued that “this legend of the Lost Cause has been an asset to the entire country” which “drew a great part of its strength from the fact that the loss itself was admitted and accepted.”[7] This interpretation, writes David Blight, ignored “just how much the Lost Cause ‘legends’ had become an aggressive racial ideology in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, fueling the virulent white supremacy at the basis of the legal and social structure of Jim Crow America.”[8] Instead, the durability of the Lost Cause stemmed from an implicit agreement among whites, North and South, that Federals and Confederates had fought for different but morally equivalent visions of the American dream. In effect, the Lost Cause was an expression of the tacit bargain by which the South accepted defeat, but in return insisted—with great success—that the North must accept the moral rectitude of the Confederate cause. This bargain Catton never challenged. And perhaps, given that it is arguably at the heart of the American Iliad, no Civil War bard could do otherwise.

MARK GRIMSLEY, A HISTORY PROFESSOR AT THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY, IS THE AUTHOR OF SEVERAL BOOKS, INCLUDING AND KEEP MOVING ON: THE VIRGINIA CAMPAIGN, MAY–JUNE 1864(2002) AND THE HARD HAND OF WAR: UNION MILITARY POLICY TOWARD SOUTHERN CIVILIANS, 1861–1865(1995). HE HAS ALSO WRITTEN MORE THAN 50 ARTICLES AND ESSAYS.

This article appeared in the Summer 2020 (Vol. 10, No. 2) issue of The Civil War Monitor.