Abraham Lincoln spent the late summer of 1862 waiting. Worrying and waiting. He was worrying about the war, which was not going well. And he was waiting for a victory so that he might issue a proclamation of emancipation that would declare most slaves free and help to win the war.

On July 1, the Union won at Malvern Hill, but the victory marked the end of the Seven Days Battles that, taken as a whole, resulted in the failure of the Peninsula Campaign that had begun in March. Richmond was safe from Union forces, and General George B. McClellan withdrew to Harrison’s Landing on the James River.

Union military affairs reached a nadir at the end of August when Major General John Pope was decisively defeated at Second Bull Run. Lincoln was despondent. Attorney-General Edward Bates described him as “wrung by the bitterest anguish—said he felt almost ready to hang himself.” Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles said the president was “sadly perplexed and distressed by events.”1

It had been more than a month since Lincoln informed the cabinet of his decision to issue an Emancipation Proclamation. He had made the decision in the aftermath of the failed Peninsula Campaign. According to Gideon Welles, at that meeting on July 22, Secretary of State William Seward said the proclamation should be postponed to a “more auspicious period” when it would not be “received and considered as a despairing cry—a shriek from and for the Administration, rather than for freedom.” Seward’s idea, “said the President, ‘was that it would be construed our last shriek on the retreat.’ (This was his precise expression.)’”2

Although Lincoln put the document aside, he did not remain still: he wrote letters that hinted at his new policy; he met with free blacks to encourage colonization and with a group of Chicago Christians to discuss the pros and cons of an emancipation edict; he continued to monitor how the border states might react, going so far as to read the draft Proclamation to James Speed, a unionist state senator in Kentucky as well as older brother of Joshua Speed, Lincoln’s closest friend.

But mostly, the president waited. Visitors described him as tired, careworn, and sad. Union morale was plummeting. And no one, in the aftermath of Second Bull Run, thought that Robert E. Lee would be content to sit still. Indeed, Lee had decided to invade Maryland, and on September 5 the Army of Northern Virginia crossed the Potomac.

On September 9, Lee issued Special Order No. 191, detailing plans for the division of his forces. His objectives included capturing the Union garrison at Harpers Ferry. Remarkably, on September 13, three Union soldiers camping near Frederick, Maryland, found the order wrapped around three cigars in an envelope. McClellan now knew Lee’s plans, yet by waiting some 18 hours to get his troops moving, failed to take full advantage of the intelligence.

Lee’s plan succeeded at Harpers Ferry, but elsewhere, at the battle of South Mountain on September 14 and into the early hours of September 15, Confederate troops faced superior numbers and sustained severe casualties. Preparing to retreat across the Potomac, they moved toward Sharpsburg, a town west of Antietam Creek. Learning that morning of the victory at Harpers Ferry, however, Lee altered his plans and decided to make a stand.

McClellan’s men began to arrive later that day and massed on the east side of the creek. Again the general waited, spending the 16th planning which allowed Lee to unite most of his forces. Everyone seemed to sense the significance of what would occur at dawn on the 17th.

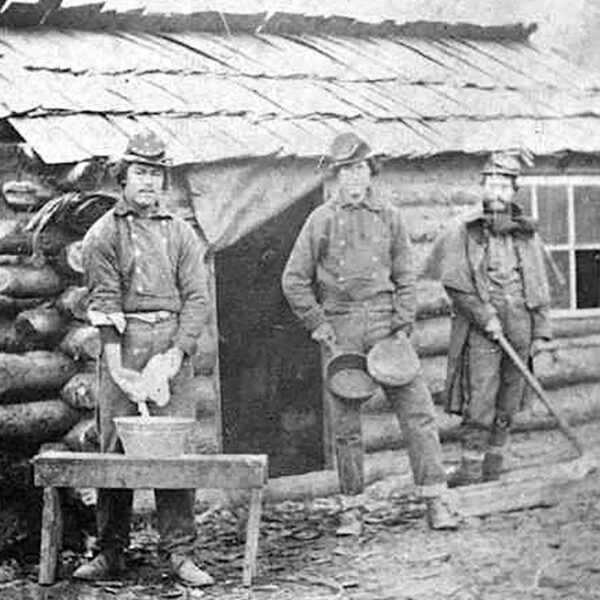

In the morning, “Fighting” Joe Hooker’s men faced Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson’s in savage combat along the Hagerstown Pike and onto a 30-acre cornfield as well as into an area known as the West Woods. One South Carolinian wrote, “never have I seen men fall as fast and thick.”3

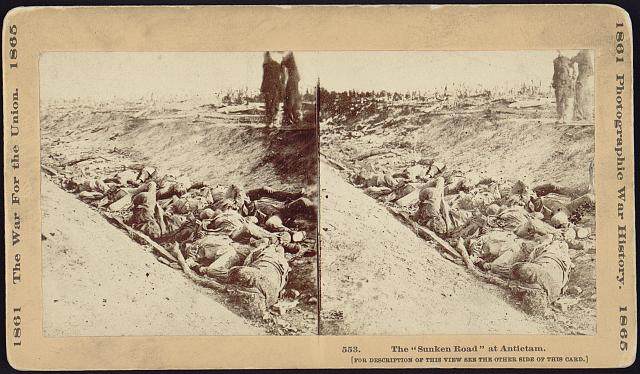

The Union attacks came serially, not simultaneously. As a result, the chance for a smashing victory by a numerically superior force was compromised and the casualties augmented. At midday, the heaviest action veered southeast, to the Sunken Road, a place soon named the Bloody Lane. Late in the afternoon, Ambrose Burnside, commanding the Union’s left flank, got his men into battle against elements of James Longstreet’s corps. For a time, the hard-pressed Confederate defenders wavered, but the arrival of A.P. Hill’s division after a forced march from Harpers Ferry stabilized the situation. The day’s fighting had ended.

Although his out-numbered army had been badly mauled, the ever-audacious Lee decided not to retreat the night of the 17th; he even contemplated going on the offensive the next day. For a time it seemed that McClellan, who was getting reinforcements, would take the fight to the rebels on the 18th, but, ever cautious, he decided not to risk it. Late in the day, Lee began withdrawing his army to Virginia.

The battle of Antietam remains the bloodiest day in American history. Here is James McPherson’s cogent summary:

“The 6,300 to 6,500 Union and Confederate soldiers killed and mortally wounded near the Maryland village of Sharpsburg on September 17, 1862, were more than twice the number of fatalities suffered in the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon on September 11, 2001. Another 15,000 men wounded in the battle of Antietam would recover, but many of them would never again walk on two legs or work with two arms. The number of casualties at Antietam was four times greater than American casualties at the Normandy beaches on June 6, 1944. More American soldiers died at Sharspburg (the Confederate name for the battle) than died in combat in all the other wars fought by this country in the nineteenth century combined: the War of 1812, the Mexican-American War, the Spanish-American War, and the Indian wars.”4

Shortly afterward, a New Hampshire surgeon wrote to his wife, “when I think of the battle of Antietam it seems so strange. Who permits it? To see or feel that a power is in existence that can and will hurl masses of men against each other in deadly conflict—slaying each other by the thousands—mangling and deforming their fellow men is almost impossible. But it is so and why we cannot know.”5

Two days after the battle, Alexander Gardner and his assistant James Gibson began taking photographs: the bodies piled in the Bloody Lane, the bodies strewn before the shelled Dunker Church, bodies buried and unburied. In October, Matthew Brady displayed the images in his New York Gallery. He called the exhibition “The Dead of Antietam.” Reviewing it, the New York Times wrote “if he has not brought bodies and laid them in our dooryards and along the streets, he has done something very like it.”6

Antietam destroyed the romance of war. Images such as Gardner’s had never before been seen. It was hard to find glory in the mangled, contorted frames of the fallen. If anyone needed reminding, Antietam showed that the conflict was literally one of life and death, for individuals as well as the nation. It proved to unionists that there was indeed a military necessity that justified taking all steps to defeat a resourceful and courageous Confederate army.

Lincoln had the victory for which he was waiting. On September 22, he issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. If the slaves were being forced to aid the Confederate war machine, by working in the fields and hauling armaments and building fortifications, he would act in his capacity as commander-in-chief to liberate that labor. One hundred days later, on January 1, 1863, Lincoln would go further: in the final Emancipation Proclamation, he decided not only to free the slaves outside of Union- controlled areas but also to enlist any black man as a soldier in the Union army.

Antietam and emancipation were linked—death and freedom. But many more gruesome battles would have to be fought, and many more strides toward freedom taken, before the war would end and slavery would be abolished. For Lincoln, the worrying was far from over.

Louis P. Masur, Professor of American Studies and History at Rutgers University, is the author of Lincoln’s Hundred Days: The Emancipation Proclamation and the War for the Union (just published by Harvard University Press).

1 Edward Bates quoted in Roy P. Basler, ed., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 9 vols. (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1953-55), V: 404; Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, ed. by Howard K. Beale, 3 volumes (New York: W.W, Norton & Company, 1960), 1:131.

2 Gideon Welles, “The History of Emancipation,” Galaxy 14 (December 1872), pp. 838-851.

3 Quoted in James M. McPherson, Crossroads of Freedom: Antietam (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), p. 119.

4 Ibid., p. 3.

5 William Child to his wife, nd, in Andrew Carroll, ed., War Letters (New York: Washington Square Press, 2001), p. 76.

6 New York Times, October 20, 1862.