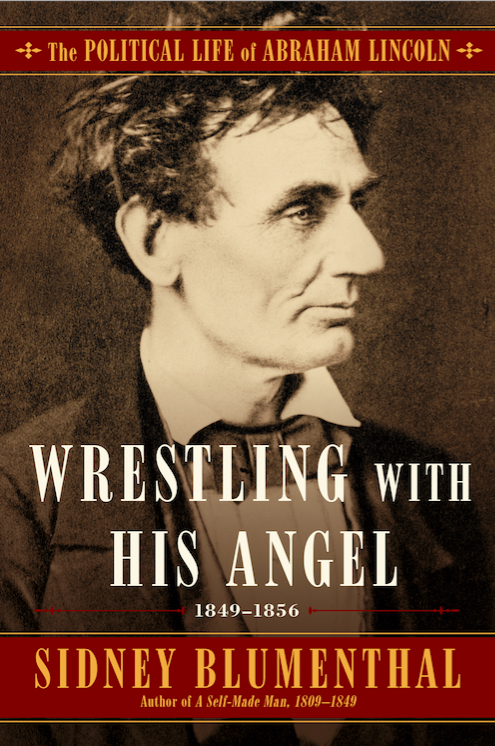

In May, Simon & Schuster released Wrestling With His Angel, the second book in veteran journalist and presidential advisor Sidney Blumenthal’s multivolume political biography of President Abraham Lincoln. (A Self-Made Man, the series’ critically acclaimed first volume, was released in 2016.) We recently sat down with Blumenthal to learn more about his work, including how he came to study Lincoln and what he’s learned about the 16th president along the way.

In May, Simon & Schuster released Wrestling With His Angel, the second book in veteran journalist and presidential advisor Sidney Blumenthal’s multivolume political biography of President Abraham Lincoln. (A Self-Made Man, the series’ critically acclaimed first volume, was released in 2016.) We recently sat down with Blumenthal to learn more about his work, including how he came to study Lincoln and what he’s learned about the 16th president along the way.

How did you get interested in Abraham Lincoln in general and his political life in particular?

When I was growing up and attending public schools in Chicago during the 1950s and early 1960s, Lincoln was a constant presence; his portrait hung in the classroom and his birthday was a state holiday. When I was about 12 years old, an older cousin took me on a trip to Springfield. With the eyes of a boy awakening to the larger world, I saw New Salem, the Old State Capitol, and Lincoln’s tomb. These sights were not in a Disney-like theme park. There was no animatronic figure with a tinny voice spouting Lincoln’s phrases to inspire a momentary false awe. Understanding demanded one’s own imagination and the pursuit of history. I began by reading Carl Sandburg’s Lincoln biography and continued from there. Serving in the White House as assistant to President Clinton I spent years working where Lincoln had lived. Afterward, I started research for a book on how presidents since Franklin D. Roosevelt have dealt with civil rights and transformed the modern political parties. I kept returning to Lincoln until I reached his beginning. Having fallen down that rabbit hole, I found it a congenial place and haven’t left yet. The more I spend time with Lincoln the deeper and broader my inquiry has gone.

Can you describe your research process? What sources have you found most reliable or insightful in your study of Lincoln?

I read through as much I can, from the newspapers of the day to the latest scholarship. When I come to a crucial aspect of Lincoln’s life I follow the footnotes until the trail runs dry. I bring to bear my own unique experience in government and politics in penetrating behind the iconic images of the personalities of the time and their motives. The past may be another country, as an English novelist said, but American politics in fundamental ways remains American politics. As a journalist, my historical research is also a journalistic enterprise. Sometimes the path leads me to letters and documents in the Library of Congress and the National Archives, which, living in Washington, are conveniently nearby. Google’s copying of whole university libraries has made it possible to wander through musty stacks without ever leaving the laptop on my desk. Gradually, old newspapers have been added to online archives and I have become familiar with the correspondents of The New York Times and the New York Tribune. Even obscure pamphlets have now been copied. My greatest frustration is the inability to interview those involved in the events. That’s why the interviews that William Henry Herndon, Lincoln’s law partner, conducted with those who knew him before the presidency are so invaluable. I am always excited to discover a memoir or a life-and-letters biography from the period that I hadn’t anticipated.

Wresting With His Angel covers 1849 to 1856, a key period in the development of Lincoln’s political skills. Which events during this time were most significant in shaping Lincoln the politician?

Wresting With His Angel covers 1849 to 1856, a key period in the development of Lincoln’s political skills. Which events during this time were most significant in shaping Lincoln the politician?

Wrestling With His Angel opens with one-term congressman Lincoln leaving Washington behind after botching his attempt to secure a federal patronage job with the incoming Whig administration. Almost at once he goes from Springfield to Lexington, Kentucky, to serve as co-counsel in a case to determine who will get the Todd family fortune on behalf of his wife and finds himself in the vortex of Kentucky politics. He contests for the estate against the leader of the powerful and virulent proslavery forces, who is married to a Todd cousin and directing the rewriting of the state constitution to end Kentucky’s restrictions on the slave trade. Lincoln loses the case as he observes the legacy of his idol, Henry Clay, and his late father-in-law, Clay’s business partner and political ally, destroyed at the hands of the Slave Power. The true heir to the Todd money is none other than a slave, who is his wife’s unacknowledged cousin and has been sent to Liberia. Decades later that boy becomes president of Liberia. Lincoln’s Kentucky experience simmers within him for years. When his longtime rival Senator Stephen A. Douglas sponsors the Kansas-Nebraska Act that repeals the Missouri Compromise, opening the way for slavery to expand into the territories, Lincoln emerges in opposition as the figure recognizable in history. Behind the scenes, he also takes on the anti-immigrant Know Nothings in order to create the Illinois Republican Party. Lincoln’s dramatic inner struggle leads him to rise in defense of the American democratic experiment, which, borrowing from Scripture, he declares cannot exist “half slave and half free.”

Have you learned anything about Lincoln during the pre-Civil War years that surprised you?

In 1864, Lincoln wrote in explaining the Emancipation Proclamation that he was “naturally anti-slavery.” Some historians state that he had little early experiences with slavery or slaves. That is the starting point for their discussion of the evolution of what they call his “maturation” on slavery. But while Lincoln’s political strategies and tactics against slavery, and his sense of urgency, did evolve with circumstances and his own responsibilities, his antislavery belief was his birthright. By “naturally” Lincoln meant just that. It was part of the fiber of his being. An antislavery preacher married his father and mother, who were functionally illiterate poor whites in Kentucky and always belonged to tiny emancipationist Primitive Baptist churches, even after migrating to the free state of Indiana in order to escape living within an economy in which Thomas Lincoln had to compete for wages with slaves. The Lincolns, as Lincoln understood it, were white fugitives from slavery. In 1856, upon assuming his new political identity as a Republican, Lincoln declared, “I used to be a slave.” He was referring to being hired out as an indentured servant until he was 21 years old by his father. Lincoln was an oppressed, poverty-stricken, and stunted boy who emancipated himself. His sense of emancipation and a free society was rooted in his own life.

What are you looking forward to examining about Lincoln’s presidency in future volumes of the series?

Wrestling With His Angel is the second volume of my four-book political biography of Lincoln. Future volumes will describe, among other aspects of Lincoln’s genius, how he engaged in the difficult and complex task of creating a new party out of political chaos; how he distilled and refined his brilliant arguments against a host of dangerous and influential demagogues, particularly Stephen A. Douglas, who manipulated and exploited every advantage of racism against Lincoln in their debates; how Lincoln outflanked the media-savvy General George B. McClellan, who became the instrument of Lincoln’s political adversaries, for control of the military; how Lincoln survived the assaults of, on the one hand, pro-Confederate “Peace Democrats,” or “Copperheads,” who branded him a tyrant, and on the other hand radical abolitionists, who disparaged him as a vacillating and compromising sellout. In the final volume, I promise to have extraordinary new material that will shed new light on the assassination, the most consequential act of political violence in American history.