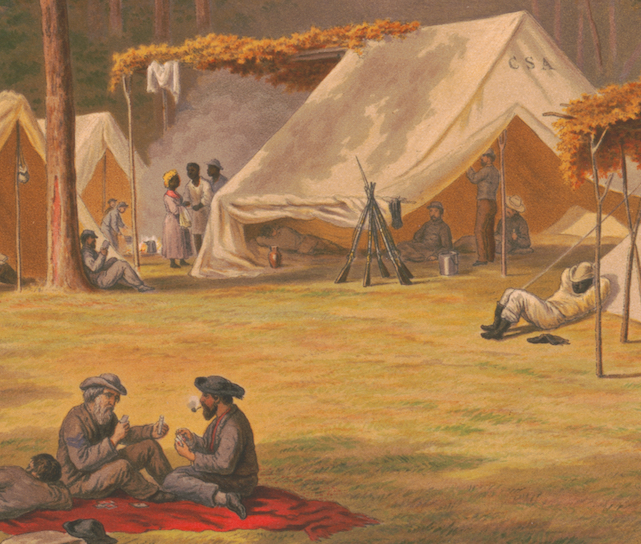

This postwar depiction of a Confederate army camp shows both soldiers and the slaves who served them while at war.

In his latest book, Searching for Black Confederates: The Civil War’s Most Persistent Myth (to be published this fall by the University of North Carolina Press), Boston-based historian and educator Kevin M. Levin tackles the enduring claim that tens of thousands of African Americans willingly fought as soldiers in the Confederate army. We recently sat down with Levin—founder of the award-winning blog Civil War Memory (civilwarmemory.com)—to learn about his work on the controversial subject.

How did you come to write a book about so-called black Confederates?

I wrote my first blog post about the black Confederate myth back in 2008. Over the years these posts have generated hundreds of comments and often heated discussion. At its core the question is not simply whether blacks served as Confederate soldiers, but how we think about and remember the place of slavery in the American Civil War. The subject bridges my interests in the history and memory of the Civil War, digital media literacy, and history education. From the beginning I was struck by the wide discrepancy between what Confederates themselves had to say about the status and role of enslaved people in the war effort and the wild claims made today about the existence of tens of thousands of loyal black Confederate soldiers. These claims can be found on thousands of websites, in history textbooks, National Park Service exhibits, and monuments, and even in the writings of two Harvard scholars. I wanted to better understand why some people insist on defending this narrative in the face of overwhelming evidence to the contrary and why others who have a sincere interest in the history of the war fall victim to this myth.

How did the idea of black Confederates become, as you note in the book’s subtitle, “the Civil War’s most persistent myth”?

What I find so striking is that during the very vocal debate over whether to allow enlistment of black men as soldiers in the southern armies—a debate that occurred throughout the Confederacy beginning in 1864 and continuing right up to the final weeks of the war—is that not a single person pointed to African Americans already serving as soldiers in the Confederate military. Regardless of their position on slave enlistment, no one in the army, in the Confederate capital of Richmond, or on the home front used the fact of existing black soldiers to bolster their position. Even in the decades following the war the white southerners who fought the conflict recalled the presence of blacks in the army, either as body servants or impressed slaves, but not as soldiers. This changed only in the mid-1970s as the memory of the war shifted in response to new research and the influence of the civil rights movement. Slavery, emancipation, and the service of black men in the Union army finally took center stage, and this did not sit well with members of the Confederate heritage community, particularly the Sons of Confederate Veterans. The SCV soon insisted that blacks were not only loyal to the Confederacy but had in fact “served” as soldiers. They commissioned books and used Confederate Veteran magazine to highlight these stories, but it was the internet that helped to spread these tales to a wider audience. Many of the websites that contain these false claims are cut and pasted from one another. Readers untrained in how to search and assess online content are easily misinformed. The ease with which new websites and social media pages can be created makes it next to impossible to challenge the black Confederate myth on a broad scale.

In Searching for Black Confederates, you also investigate the roles that African Americans actually performed in the Confederate army. What were these? And did you learn anything that surprised you?

Enslaved labor was vital to the success of the Confederate war effort. Tens of thousands of impressed slaves worked in hospitals, constructed earthworks, repaired and extended rail lines, and helped manufacture artillery in places like the Tredegar Iron Works in Richmond. Impressed slaves also performed a wide range of important roles in the armies. Confederate armies also included thousands of body servants (what I refer to in the book as camp slaves), who accompanied their masters to the front. These men functioned outside the military hierarchy entirely. They tended to their masters’ every need, including cooking, tending horses, foraging, cleaning, and serving as messengers with families back home. This mobilization of black bodies helped to offset the population difference between North and South and made it possible for the Confederacy to maximize the number of white men that could shoulder a rifle in the ranks.

General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia may have included anywhere between 6,000 and 10,000 enslaved men in the summer of 1863. Their presence—and the important roles they played—helped to place the preservation of slavery at the center of the Confederate war effort. Regardless of whether a Confederate soldier owned a single slave, he was reminded on a daily basis that the army could not function without the assistance of enslaved labor. Confederate armies were an extension of a society that depended almost exclusively on enslaved labor. Understanding just how pervasive enslaved people were in the armies can help us to appreciate what Vice President Alexander Stephens referred to as the “cornerstone” of the Confederacy.

What sources did you find particularly useful or important in your research?

Historian and author Kevin M. Levin

Some of the most misunderstood sources today are Confederate pensions that were issued decades after the war to a small number of former camp slaves. Scans of these documents are found on websites today as purportedly clear evidence that African Americans served as soldiers in the Confederate army—even though the documents themselves indicate that they were issued to former slaves, not to soldiers. The pensions tell us very little about the war itself and much more about how white southerners at the beginning of the 20th century used the loyal slave narrative to maintain a Jim Crow culture at a time of increased racial tension. The loyalty and obedience of former camp slaves stood in sharp contrast to a younger generation of African Americans who pushed for civil rights during the period and especially after having returned from World War I to make the world “safe for democracy.”

Applicants for these pensions clearly understood that as a condition of approval they were expected to offer testimony of their loyalty to their former masters and the Confederacy, but they also likely used the process to demonstrate their bravery and steadfastness in the midst of danger. The brief responses to specific questions and longer accounts provided by these elderly men can be read as claims to their own martial manhood—feelings that during wartime had probably been denied or dismissed every time they were referred to as “uncle” or “boy.”

How hopeful are you that the black Confederate myth will ever be completely debunked? Do you see it as growing or waning in strength?

You can still find hundreds of websites that support the black Confederate myth. This will continue as long as we neglect to teach students how to search for information online and assess the content of websites. That said, there is reason to be optimistic. During the Civil War sesquicentennial, state commissions, the National Park Service, and other organizations highlighted a narrative that included the service of black Union soldiers and asked the public to consider difficult questions related to the history of slavery and race in America. Black Confederates were hard to find beyond events sponsored by the Sons of Confederate Veterans and the United Daughters of the Confederacy. In the wake of Dylann Roof ’s murder of nine churchgoers in Charleston in 2015 and subsequent calls to remove Confederate flags and monuments from public spaces, the SCV once again trotted out the black Confederate narrative to argue that the war had nothing to do with the preservation of slavery. These calls fell on deaf ears. A proposal made by two South Carolina Republican state legislators in October 2017 to erect a monument to black Confederates on the statehouse grounds also failed to attract serious attention. It is safe to assume that as long as we continue to debate the cause and legacy of the Civil War we will continue to see appeals to fictitious black Confederates.

You can still find hundreds of websites that support the black Confederate myth. This will continue as long as we neglect to teach students how to search for information online and assess the content of websites. That said, there is reason to be optimistic. During the Civil War sesquicentennial, state commissions, the National Park Service, and other organizations highlighted a narrative that included the service of black Union soldiers and asked the public to consider difficult questions related to the history of slavery and race in America. Black Confederates were hard to find beyond events sponsored by the Sons of Confederate Veterans and the United Daughters of the Confederacy. In the wake of Dylann Roof ’s murder of nine churchgoers in Charleston in 2015 and subsequent calls to remove Confederate flags and monuments from public spaces, the SCV once again trotted out the black Confederate narrative to argue that the war had nothing to do with the preservation of slavery. These calls fell on deaf ears. A proposal made by two South Carolina Republican state legislators in October 2017 to erect a monument to black Confederates on the statehouse grounds also failed to attract serious attention. It is safe to assume that as long as we continue to debate the cause and legacy of the Civil War we will continue to see appeals to fictitious black Confederates.

This article appeared in the Fall 2019 (Vol. 9, No. 3) issue of The Civil War Monitor.