It had been just one month since the Confederates attacked Fort Sumter in April 1861, launching the Civil War. Texas and ten other states seceded from the Union and then formed the Confederate States of America, with Jefferson Davis as president. Abraham Lincoln issued a proclamation for 75,000 militiamen, readying the Federals for war while the South began to recruit.

Davis authorized Benjamin Franklin Terry, a local celebrated figure in Texas, to raise a regiment. The 40-year-old wealthy businessman had made a name for himself during the First Battle of Bull Run in Fairfax, Virginia, by shooting down a United States flag from atop a courthouse after the Rebel victory. It sealed his reputation with Confederate leaders as a brazen patriot. He would soon become the patriarch of the 8th Texas Cavalry, better known as Terry’s Texas Rangers.

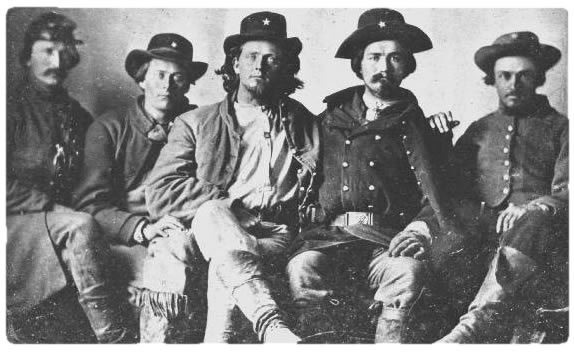

On September 9, 1861, roughly 1,200 men from all walks of life were mustered into service in Houston as the war began. They were college boys, white-collar workers and men raised in the saddle. They were experts with lariats, six-shooters and in bareback riding.

The Rangers were required to bring their own clothes, supplies and any weapons they could carry, usually double barrel shotguns, pistols and Bowie knives. Most chose to don Mexican ponchos and slough hats pinned with the five-point star of the original Texas Rangers. The Confederacy could only afford to outfit them with horses.

The enrolling officer asked the newly formed regiment: “Do you men wish to be sworn into service for twelve months or for three years or for the duration the war?” With loud unanimity, the men shouted, “For the war, for the war!” with most not expecting to return home until it was over.

Terry selected commanders with solid combat skills; the majority were former Texas Rangers and military leaders. Many had fought Indians all over the state and learned how to take control during a battle.

Even before they stepped onto a battlefield southerners knew who they were, mostly because of their name not their skills. During a stop in Tennessee the ladies of Nashville, upon hearing that the Texas Rangers were setting up a temporary camp, expected a Wild West Show. The men hopped on horses and raced to see who could pick up silver coins off the ground the fastest. They were not Texas Rangers, the legendary lawmen from the rough frontier, but they were expected to uphold that image. It was a reputation they never earned but were expected to fulfill, and they did.

Their first real engagement was the Battle of Woodsonville three months later. Ranger leaders had drilled them on combat tactics but they were mostly ordered to do whatever it took to win. While the Union soldiers formed an orderly square formation, Terry’s Boys wildly charged them, firing their shotguns and bellowing the Texas Yell. While the outcome of the battle was inconclusive, they quickly became a type of a “shock troop,” a regiment reared to lead an attack.

The Rangers went on secret missions, often donning blue overcoats for maximum deception; they destroyed railway and telegraph lines, sneaked behind enemy lines and gunned down Yankees at close range with no regard for their own lives. They often led the front as well as covered the rear, the first and last line of offense and defense.

They were street-wise cowboys, often reckless, most of the time untrained, but always committed to their mission. Rangers usually did the dirty work other soldiers didn’t stomach. Because they rarely took prisoners under the order of their commanders, Terry’s Texas Rangers were known for ruthlessly ridding themselves of Union threats. A Confederate colonel once suggested that an outnumbered Union regiment surrender because “he had five hundred Texas Rangers he couldn’t control in a fight.”

Their reputation for misbehavior, ranging from rowdiness to lawlessness, preceded them. During the first few months of the war, the Rangers left Tennessee because more Rebels were needed in Kentucky, a Union state — at least that was the official story. One Ranger revealed a more pressing reason.

One night in Nashville, three or four Rangers slipped out of their barracks, got drunk and went to a theatrical performance about Captain John Smith and Pocahontas. When the actress playing Pocahontas was roughed up on stage for preventing Smith’s execution, one Ranger took offense to the mistreatment of the lady and fired his six-shooter at the offending actor. The soldier missed Pocahontas’ father, but he managed to kill two police officers and wound another. The governor of Tennessee furiously demanded that that the Texas Rangers leave his state immediately.

This gusto for a fight served them well in battle. A captured Union officer wrote in a letter: “The Rangers are as quick as lightning. They ride like Arabs, shoot like archers at the mark, and fight like devils. They rode upon bayonets as if they were charging a commissary department, are wholly without fear themselves, and no respecter of a wish to surrender.”

They were initially bound for the Eastern Theater where the Battle of Gettysburg was eventually fought but were redirected to the Western Theater to join General Albert Sydney Johnston’s army. In four years the Rangers participated in almost 300 engagements including some of the bloodiest battles of the war including Shiloh, Chickamauga, and Chattanooga as well as the Atlanta Campaign.

Their tenure with the Rebels was not without controversy. They participated in the Battle of Fort Pillow where Union soldiers, both black and white, were gunned down after surrendering. One unnamed Ranger was credited with saving the life of a black Federal, but it’s clear from letters and diaries that the regiment’s overall attitude towards black soldiers was negative.

Near the end of the war, Ranger Alexander Shannon created a scouting group that infiltrated Sherman’s lines during the Atlanta Campaign. “Shannon’s Scouts” made raids and went on reconnaissance missions, killing and capturing Federals along the way. Though their attempts at slowing Sherman’s March to the Sea were futile, their disruptions caused the Union to put up a $5000 reward for Shannon’s capture.

Terry’s Texas Rangers left the war as legends—one of the most effective cavalry units in the Confederacy. Of the more than 1,000 men who were mustered in, less than 300 returned home.

In 1907, more than forty years after the war, some of the surviving Rangers gathered in Austin for the dedication of a monument on the Texas Capitol grounds. It is a bronze statue depicting a Terry’s Texas Ranger wearing a poncho, a slouch hat and carrying a shotgun astride a spirited horse. One of the inscriptions is, “There is no danger of a surprise when the Rangers are between us and the enemy.”

With more than 17 years in television news, Kate Dawson has worked as a field producer, line producer, and writer for some of the top news organizations in the country. She’s also a documentary filmmaker, working with some of the top directors in the country. Dawson holds a MS degree in journalism from Columbia University and was on the faculty at Fordham University’s journalism school in New York for two years where she was the faculty advisor for one of the student newspapers. She’s a senior lecturer at the University of Texas School of Journalism. Dawson is the author of The Digital Reporter. You can follow her at twitter.com/kwinklerdawson.

Sources: Bryan S. Bush, Terry’s Texas Rangers: History of the Eighth Texas Cavalry (Nashville: Turner Publishing Company, 2002); Thomas W. Cutrer, Our Trust is in the God of Battles: The Civil War Letters of Robert Franklin Bunting, Chaplain, Terry’s Texas Rangers (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2006); Thomas W. Cutrer, The Terry Texas Ranger Trilogy (Austin: State House Press, 1996); Leonidas Giles, Terry’s Texas Rangers: The 8th Texas Cavalry in the Civil War (Austin: Von Boeckmann-Jones Publishers, 1911); H.W. Graber, The Life Record of H. W. Graber: A Terry Texas Ranger 1861-1865, Sixty-two Years in Texas, reprint (Austin: State House Press, 1987); Kevin Ladd, Chambers County, Texas in the War Between the States (Baltimore: Gateway Press, 1984); Terry’s Texas Rangers Papers, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin.