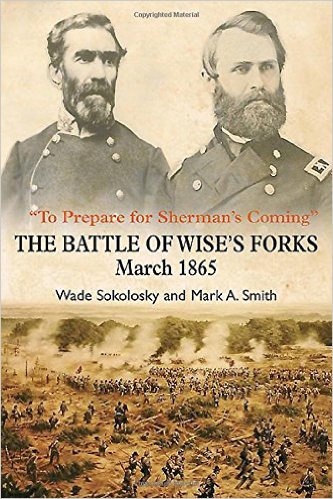

“To Prepare for Sherman’s Coming”: The Battle of Wise’s Forks, March 1865 by Wade Sokolosky and Mark A. Smith. Savas Beatie, 2015. Cloth, ISBN: 978-1611212662. $27.95.

At the outset of Ken Burns’s award–winning documentary The Civil War, narrator David McCullough intones that the war “was fought in 10,000 places,” listing often-obscure sites as Valverde, New Mexico, and Tullahoma, Tennessee. “Men who had never strayed twenty miles from their own front doors now found themselves soldiers in great armies fighting epic battles hundreds of miles from home.”

At the outset of Ken Burns’s award–winning documentary The Civil War, narrator David McCullough intones that the war “was fought in 10,000 places,” listing often-obscure sites as Valverde, New Mexico, and Tullahoma, Tennessee. “Men who had never strayed twenty miles from their own front doors now found themselves soldiers in great armies fighting epic battles hundreds of miles from home.”

The battle of Wise’s Forks, North Carolina, fought in March 1865, did not make the documentary’s roll call of seemingly inconsequential martial encounters, nor does it rank among the conflict’s epic battles. The filmmakers were not alone in ignoring this fight, one of many in the chess game that led to the end of America’s bloodiest conflict. For instance, none of those who contributed to what became Battles and Leaders of the Civil War allude to Wise’s Forks, which the editors of the volumes relegated to a footnote.

Until authors Wade Sokolosky and Mark A. Smith turned their attention to this encounter, the battle remained generally unfamiliar to students of the war. Known by various spellings and names, Wyse’s Forks and Kinston among them, the battle has gone without scholarly treatment. Now, in their handsomely designed volume, “To Prepare for Sherman’s Coming”: The Battle of Wise’s Forks, the coauthors offer an in-depth study of an engagement wherein two cobbled together armies fought for the control of the Neuse River and crossings that spanned an adjacent waterway.

By February 1865, the Confederacy was in tatters but still stubbornly resisting. With Major General William Tecumseh Sherman ravishing South Carolina (and threatening a northward march to link up with Union forces in Virginia), Ulysses S. Grant sought to facilitate his junior commander’s movements. One goal was to secure the Atlantic and North Carolina Railroad between the coastal river port city of New Bern and Goldsboro, in the interior of North Carolina. From there, all roads led to Petersburg and Richmond.

Union Gen. Jacob Cox, selected to head the forward movement, had proved himself a diligent officer throughout the war. Needing to block the move, Confederate Gen. Joseph Johnston took the risky step of diverting some of his troops—who were gathering for a face off against Sherman’s advance force—to thwart Cox’s maneuver. The two armies clashed near Kinston, midway between New Bern and Goldsboro, along a tributary of the strategic Neuse River.

Cox headed up a three-division provisional corps that contained many untried occupation-force soldiers from Beaufort. Indeed, in evaluating the initial battle performance of some of his units, an exasperated Cox wrote that they were “little better than militia” (139). Cox’s opponent, the veteran-though-mercurial commander Braxton Bragg, was also forced to rely on some callow troops. However, Bragg did have generals Daniel Harvey Hill and Robert Hoke—both battle-tested subordinates—and their still reliable veterans from the armies of Tennessee and Northern Virginia.

On March 8, when Hill and Hoke’s Confederates suddenly appeared on the flanks of the most forward Union divisions, the federals suffered a near- debacle. Here were some of the least experienced soldiers in Cox’s army; new recruits even stocked the veteran regiments among them. The 27th Massachusetts, for example, which had previously been decimated at Drewry’s Bluff, Virginia, was now filled with green troops. Complicating the choice of divisions serving in the advance, the forward commands had a gap in their alignment, while the rear division, filled with seasoned men, was not within supporting distance.

Sokolosky and Smith devote the longest of their ten chapters to the initial Confederate attack, which netted nearly one thousand Union prisoners. For this, the authors credit Hill and Hoke, the two experienced rebel commanders. Conversely, they criticize the much maligned Bragg for then recalling Hill’s attack, as the rebel general mistakenly believed Hill’s men were needed elsewhere. Bragg’s failure stemmed from what the authors’ term “his lack of awareness of how the battle was unfolding” (111). They further assert that this lapse constituted “the greatest blunder committed by the Confederates on March 8” (130).

Meanwhile, survivors of the battered Union divisions had retreated a short distance eastward, where they were reinforced by the veteran troops. Cox, able to exert more direct control over his consolidated and still much superior force, had his men erect fortifications along a well-placed second line of defense. From that position, Cox’s makeshift army held off sporadic attacks on the last two days of the inconclusive battle.

Given that the book is a detailed account, a necessary fault in any tactical battle study, the narrative is generally fast paced. The authors display a mastery of the battlefield’s swampy terrain and, for the most part, describe the unit deployment with aplomb and skill. Their judgment of Bragg is fair minded, although, minus his interference, had his troops achieved more in the flank assault on March 8, it is doubtful to this reviewer whether greater success would have altered the outcome. With or without Bragg’s decision to halt Hill’s attack, the Confederate goal of delaying the Union advance on Goldsboro was, as the authors acknowledge, achieved. Union supply trains would not reach Goldsboro for another two weeks.

Though apparently not their intention, the authors’ study offers more than yet another drums and bugles account of a Civil War battle. As retired military officers, Smith and Sokolosky fully understand the importance of logistics in warfare. The ten pages they devote to the transport of Hood’s former army from Tupelo, Mississippi to the Carolinas, via the South’s all but broken rail system, is the most thorough this reviewer has read.

What is more, the description they provide of mounting desertion during the movement contrasts dramatically with the decision of thousands of other soldiers to endure the punishing rail transfer. Such dichotomies tell us much about the decaying state of Confederate nationalism, as opposed to the remarkable staying power of rebel irreconcilables in the last winter of the war.

The book is footnoted, contains well-researched appendices, an index, bibliography, and twelve maps. It is enhanced by over seventy-five illustrations.

Thomas M. Grace is the author of Kent State: Death and Dissent in the Long Sixties (2016).