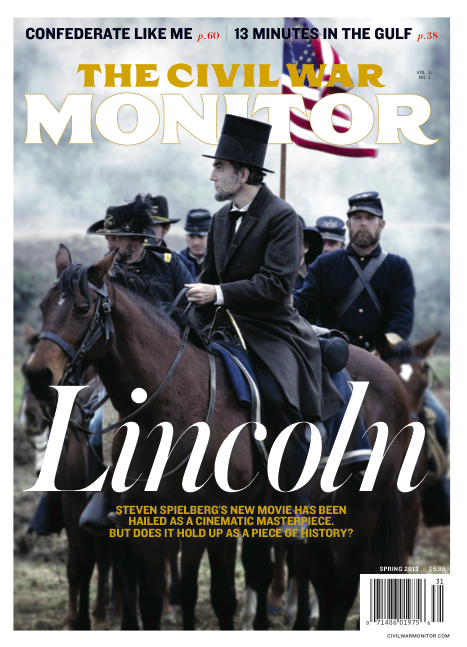

As a special “thank you” for being an eNews subscriber, we wanted to give you an exclusive sneak peek into the Spring 2013 issue. This issue’s feature article is entitled, “Lincoln Considered”—a five-part series on the Spielberg blockbuster.

Below is Jason Emerson’s take on the film and Sally Field’s portrayal of Mary Todd Lincoln.

****************************************************

Sally Field / Mary Todd Lincoln

by Jason Emerson

Mary Lincoln has been portrayed on the big and small screens by actors in dozens of iterations, ranging from the staid and self-important Lincoln based on Gore Vidal’s novel in 1988 (as played by Mary Tyler Moore) to the recent (and hilarious) Geico insurance commercial in which Mary asks “honest” Abraham, “Does this dress make my backside look big?” The celluloid Mary—sometimes a major character, sometimes a minor one—has been ridiculed, reviled, and revered. But has any screenwriter, director, or actor ever captured in the finite space of film the true personality and essence of Mary Todd Lincoln?

The answer: Yes—Tony Kushner, Steven Spielberg, and Sally Field in Lincoln.

Now Hollywood is Hollywood, and no historic film or film adapted from a book is ever 100 percent accurate. The portrayal of Mary Lincoln in Lincoln was not perfect, but it was certainly the best ever offered on screen.

It was, succinctly, spectacular.

One of the film’s great scenes has Mary confronting Thaddeus Stevens and other Radical Republican House members at a White House reception, asking them playfully (yet seriously) if they were going to investigate her household spending in committee again. This was a reference to her over-spending her $20,000 congressional appropriation in 1861 to redecorate the White House. The conversation becomes a verbal sparring in which Mary’s repartee shows her intelligence, humor, sarcasm, venom, and fiery strength: Her spine of steel and a flash in her eyes dare Stevens to question or judge her once more. The writing and acting are brilliant, and leave the audience cheering her strength and cheekiness. And this was one side of the real Mary: someone who would not back down from a fight and would stand up for herself and her husband. “How the people love my husband,” she taunts in her conversation with Stevens, insinuating that they will never love him in the same way and he should not attempt to thwart the president’s will.

Another great aspect of the scene is Lincoln himself. When the camera pans back to show Lincoln watching the exchange, his look of pride and admiration (and even a hint of smugness) is a profound flourish that shows why he fell in love with her—and why he loves her still.

The movie captures the other side of Mary in the scenes of her and Lincoln alone together, when her petulance, jealousy, self-indulgence, and pitiableness also shine through. Mary’s first scene is in the Lincoln’s White House bedroom. Wearing her shift at her dressing table, looking a bit disheveled, her hands shake slightly and she seems emotionally overwrought, even on the brink of a nervous breakdown. She’s still grieving for her dead son Willie, stressed about the war, and worried about her husband and his place as president.

In another scene Abraham and Mary have a shouting match in which Mary can consider nothing but her own needs and Abraham lashes back, reminding her that when their youngest son, Tad, was sick after Willie’s death, she locked herself away and ignored Tad. He says that he grieves Willie’s death too, but has the sense and decency to consider others. “Just once don’t think of yourself,” he thunders. “I should have clapped you in the madhouse.” To this, Mary replies only with continued self-indulgence and self-pity.

Mary Lincoln was a woman of extremes who, for all her virtues, had numerous faults. As White House Secretary William O. Stoddard wrote, “It was not easy, at first, to understand why a lady who could be so kindly, so considerate, so generous, so thoughtful and so hopeful, could, upon another day, appear so unreasonable, so irritable, so despondent, so even niggardly, and so prone to see the dark, the wrong side of men and women and events.” This dichotomy, this complexity, was perfectly pitched, balanced, and tuned by Sally Field. Field did not merely portray Mary; she imbued her, she channeled her. She quite simply was Mary Lincoln.

Both Field and Kushner achieved what many historians have failed—rather than trying to either vindicate or blame Mary for her personality and her actions, they seek to understand who she was. Kushner particularly offers this in a presentist attempt to address Mary’s historical reputation. During Mary and Abraham’s carriage ride on the day of the assassination, Mary tells her husband, “All anyone will remember of me is I was crazy and I ruined your happiness.” She also tells him that if future generations want to understand him, “They should look at the wretched woman by your side.” While Mary

certainly never would have said such things at the time, Kushner’s intent is to connect past and present, to suggest the closeness of Abraham and Mary and the need to understand her to fully understand him. Mary Lincoln was a vital part of her husband’s life, but she was a fascinating, impressive, and misunderstood person in her own right. Tony Kushner’s pitch-perfect writing and Sally Field’s impeccable acting have brought Mary Lincoln to life on the silver screen in a balanced and realistic way, one that many historians, quite frankly, did not think possible.

An independent historian and professional journalist, Jason Emerson is the author of numerous books and articles about Mary Lincoln and members of the Lincoln family, including The Madness of Mary Lincoln (2007) and Giant in the Shadows: The Life of Robert T. Lincoln (2012).