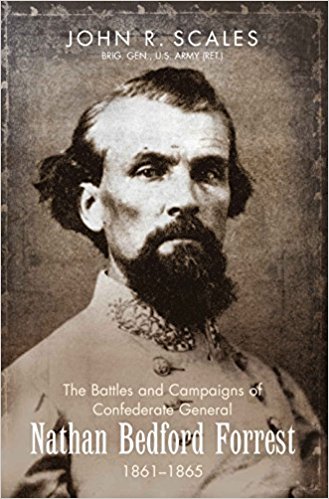

The Battles and Campaigns of Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest 1861-1865 by John R. Scales. Savas Beatie, 2017. Cloth, IBSN: 978-1611212846. $32.95.

In 1868, with the nation in the midst of a contentious political realignment and social restructuring after the Civil War, two former Confederate officers, Thomas Jordan and T.J. Pryor, met in Memphis with the South’s most controversial general to write a history of his battles and campaigns. Now, with the nation again undergoing a reexamination of many of its cultural assumptions and social relationships, another former officer, John R. Scales, is bringing his military experiences to bear on the battles and campaigns of the same, and still controversial, general.

In 1868, with the nation in the midst of a contentious political realignment and social restructuring after the Civil War, two former Confederate officers, Thomas Jordan and T.J. Pryor, met in Memphis with the South’s most controversial general to write a history of his battles and campaigns. Now, with the nation again undergoing a reexamination of many of its cultural assumptions and social relationships, another former officer, John R. Scales, is bringing his military experiences to bear on the battles and campaigns of the same, and still controversial, general.

Nathan Bedford Forrest has been a lightning rod for all manner of historians and sociologists for more than 150 years. But where these scholars—professional and popular alike—usually agree is that Forrest was a brilliant operational commander, an instinctive battlefield tactician, and a charismatic leader of men under fire. They may even agree with his most skilled opponent, Union Major General William T. Sherman, who said that “Forrest was the most remarkable man our Civil War produced on either side…he had a genius for strategy which was original, and to me incomprehensible.” Retired Brigadier General Scales agrees with Sherman. Nevertheless, he valiantly attempts, and in the main succeeds, in making Forrest’s military career comprehensible to the twenty-first century reader.

Scales gives no biographical background, which would have been helpful in understanding how Forrest became the man he did. His pre-war evolution from abject poverty to wealthy prominence based on a profitable slave trading enterprise often impacted his operational style. His explosive personality undoubtedly influenced his relationship with superior officers and his struggle with the politics of military hierarchies. Equally absent is an account of Forrest’s postwar life and his connection with the Ku Klux Klan, which fuels much of the controversy surrounding the general today. Scales has opted for a purely military examination revolving around Forrest’s operational art, the “planning and executing military campaigns.” For Scales and modern military practitioners, it is “the true realm of the general officer—or at least the realm of the general’s authority and responsibility.” In operational art, Scales finds Forrest first rate.

It’s no exaggeration to say that Forrest became a legend in his own time. It began early in the war, when he refused to surrender with most of the Confederate garrison at Fort Donelson and led his cavalry and others on a daring nighttime escape. Throughout the Western Theater, his audacious forays behind Union lines, decisive defeats of cavalry expeditions sent against him, capture and destruction of much Union war material, and uncanny ability to repeatedly reorganize and refit his command made Forrest a hero to most Southerners.

Forrest chafed at control. But when in command on the battlefield, Forrest and his men acquitted themselves admirably at places like Fallen Timbers, Murfreesboro, Okolona, Hog’s Mountain, Brice’s Crossroads, and numerous other engagements. He also performed duties usually associated with cavalry operations such as screening and reconnaissance for the Army of Tennessee under its various commanders. Forrest’s performance in set-piece battles, however, requires a more nuanced evaluation. In these engagements, Forrest was subordinate to a higher ranking officer and his men fought in concert with other units. Scales provides the information necessary for readers to make informed judgments regarding Forrest’s actions at Shiloh, Chickamauga, Harrisburg, Franklin, and Nashville.

The most controversial action of Forrest’s career occurred at Fort Pillow on April 12, 1864. Scales rightly concludes, “In purely military terms, Fort Pillow was a minor action that had no significant effect, but as a propaganda event it had a profound impact on the war.” As to the massacre of more than 300 soldiers, most of them African American, after they had surrendered, Scales finds “no creditable evidence indicates that Forrest ordered or even condoned the executions of prisoners, although neither did he appear to investigate the later allegations. Unquestionably, this incident is an ugly blotch on the reputation of both Forrest and his cavalry.” It is a reputation that Forrest carries to this day.

Scales’ narrative style reflects his years immersed in a military environment. It is data driven and dense with specific names, numbers, and distances. There is more narrative than analysis; facts predominate opinion. This is not to criticize Scales’ scholarship, but those seeking a stirring rendition of Forrest’s exploits would be better served by reading Shelby Foote.

Savas Beatie’s numerous Civil War publications make it convenient for readers seeking source references by putting footnotes at the bottom of the page. Including numerous maps provides useful visual clarification of the geography being described. Usually, the detailed driving directions that allow today’s readers to retrace the movements described in the book are a welcome addition to the historical text. But when following Forrest, the depth of detail Scales provides might overwhelm even the most careful GPS navigator. Take, for example, just a portion of the directions for following Forrest’s route from Fort Pillow back to Mississippi: “In 1.3 mi turn L on CR242 (this is Molino) & bear R at 0.7 mi (still CR 242), go 0.8 mi, then L on CR 157. In 0.1 mi turn R on CR 241 & go 0.4 mi to MS 30.” It goes on like this all the way to Tupelo. Little wonder that Union cavalry never caught up with the gray raider and his hard riding marauders.

Forrest has been the subject of more than 50 books and countless articles. Some are pure hagiography; others are unabashedly damning. Most, however, reflect the complexity of the man himself. Readers looking for a professional presentation of all facets of Forrest’s military activities will profit by consulting Scales’ comprehensive accounting. Forrest might say that Scales, while not getting there first, certainly got there with the most: the most, at least, since Jordan and Pryor—and that’s saying a lot.

Gordon Berg’s articles and reviews have appeared in many Civil War periodicals. He writes from Gaithersburg, Maryland.