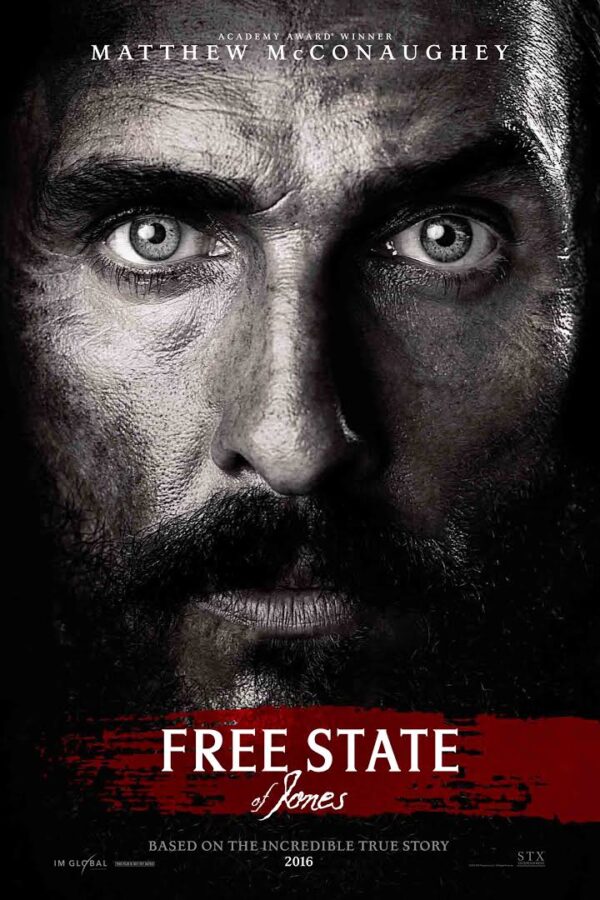

Free State of Jones directed by Gary Ross. Runtime: 2 hours, 19 minutes. Release date: June 24, 2016.

*SPOILER ALERT*

Written and directed by Gary Ross, Free State of Jones chronicles how an interracial alliance of Confederate deserters (along with their kin) and runaway slaves waged a class-based insurgency against the Confederacy. Operating in the Piney Woods region of Mississippi and led by Newton Knight (Matthew McConaughey), members of the group—also known as the “Knight Company”—united in protest against what they believed to be a “rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight.” Together they took up arms against a government that routinely conscripted their men to defend slaves they didn’t own and confiscated their property without compassion—all while allowing elite members of the slavocracy and their sons to dodge service via the “twenty negro rule.”

Written and directed by Gary Ross, Free State of Jones chronicles how an interracial alliance of Confederate deserters (along with their kin) and runaway slaves waged a class-based insurgency against the Confederacy. Operating in the Piney Woods region of Mississippi and led by Newton Knight (Matthew McConaughey), members of the group—also known as the “Knight Company”—united in protest against what they believed to be a “rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight.” Together they took up arms against a government that routinely conscripted their men to defend slaves they didn’t own and confiscated their property without compassion—all while allowing elite members of the slavocracy and their sons to dodge service via the “twenty negro rule.”

To be very clear from the start, Free State of Jones is not an expose on the gruesome realities of southern slavery in the model of Roots (1977), 12 Years a Slave (2013), or the forthcoming The Birth of a Nation (slated for release in October 2016). That fact, however, doesn’t mean Ross has whitewashed the institution for sake of a more pleasant viewing experience. Branded cheeks, slave collars, families torn apart, and white-on-black rape are all clearly present in the story. One non-violent but equally heartbreaking scene involves a slave named Rachel (Gugu Mbatha-Raw) spying on her master’s children in a desperate attempt to learn to read—an effort that brings her into non-consensual sexual contact with her wealthy owner, James Eakins. Later, when Rachel resists Eakins’s advances, he whips her back bloody.

At the same time, despite the misguided attempts of certain pundits to paint it as such, this is not another “white savior” story in the tradition of Mississippi Burning (1988), A Time to Kill (1996), or Amistad (1997). There are no absolute victories or moments for grinning self-congratulation to be had. Every wartime gain made by the insurgents comes with a significant cost in blood and treasure; some of the group’s most hated enemies—most notably Lieutenant Barbour—survive the war and thrive in its aftermath. Moreover, while white and black members of the Knight Company fight together against a common enemy, the film never depicts race relations within the group as uniformly harmonious. For much of the time spent camping in the swamp between raids, black men and women remain segregated and white insurgents are openly skeptical of Knight’s relationships with ex-slaves.

Regarding those interracial relationships: on one hand, it’s difficult to overlook the fact that Newt Knight’s transition from deserter to guerrilla leader involves being chased by a slave posse’s “nigger dogs” and then requires the help of multiple enslaved guides. On the other hand, it’s equally difficult to overlook how his whiteness afforded him privileges not available to his black comrades—such as his son not being subject to an “apprenticeship.” Simply put, Knight’s interactions with enslaved characters are generally believable because while he does become an outlaw through a process familiar to runaway slaves, and while he shares an anti-elite bond with them, filmmakers are cautious not to insinuate that this ever allowed Newt to experience the Civil War or Reconstruction as if he were black.

This is critically important to the last third of the film, when the war ends and resistance to the Confederacy no longer constitutes a socio-economic bond for white and black insurgents. At this point, white supremacy gradually regains dominance in Jones County, and Knight’s vision of a yeoman-dominated “Free State”—where the game isn’t rigged to make some men rich by keeping other men poor—disintegrates amidst a backdrop of broken political promises, the implementation of Black Codes and apprenticeship laws, the marauding of hooded nightriders, and of votes cast at gunpoint but never counted. Even Moses Washington (Mahershala Ali), a former slave who becomes Knight’s closest friend during and after the war, is castrated and hanged by a white lynch mob after successfully registering dozens of local freedmen as Republicans.

With this in mind, the point really isn’t that Newt Knight is good or bad at filling the role of white savior. It’s that in many ways, Reconstruction failed class-minded whites like Newt Knight and blacks seeking citizenship like Moses Washington all at once—and that to be a savior was not only unrealistic under such lopsided, bigotry-fueled circumstances, it was simply impossible. Even so, the film manages to salvage a whisper of hope from the wreckage. The spirit that kept Knight and his allies swimming against the tide in the 1860s and 1870s was passed to their progeny: descendants like Davis Knight, who defied Mississippi law and married a white woman despite having a black great-grandmother. Through this storytelling mechanism, Ross cleverly connects the populist opportunity lost during Reconstruction to the racial oppression of the Jim Crow South—but also hints that with continued defiance comes slow change.

Perhaps better than any other film save for Ride with the Devil (1999), Free State of Jones reenacts how wartime violence unfolded on the homefront—and exposes the extent to which the boundary between battlefront and homefront was a creation of the postwar period. Better still, the film pieces together a portrait of the Civil War South the likes of which has never before emanated from Hollywood. Missing are the perfectly manicured plantations and happy-go-lucky slaves of Gone with the Wind (1939) and the romantic unions that transcend political reality of The Horse Soldiers (1959). Absent is the uniform southern dedication to the Confederacy of The Birth of a Nation (1915) and gone are the apotheosized elites of Gods and Generals (2003). Instead, one Lost Cause trope after another is shattered against the gritty counter-narrative of men and women who temporarily erased the color line in defiance of everything the architects of the Confederate Experiment hoped to achieve.

This is, of course, not to imply that the film doesn’t have content problems. For one thing, because it attempts to cover both the war years and Reconstruction, certain backstories are neglected and relationships left undeveloped. It’s difficult to hold ambition against Ross, however, because had he not attempted to push the narrative forward into the 1870s, reviewers would undoubtedly be critiquing that decision as well. For my money, more detail isn’t perfect, but it’s better than not enough. Less forgivable is the leap of faith audiences are expected to take in accepting the post-war friendship of Serena Knight (Keri Russell), Newt’s first wife who abandoned Mississippi when he rebelled against the Confederacy, and Rachel Knight, his second, African American wife. After the war, a destitute Serena not only returns to Mississippi with Newt’s white son, but also takes up residence with Newt, Rachel, and the couple’s mixed race child without so much as a glare or an unfriendly word. Luckily, there’s a solution to both of these pleas for more information: read Victoria Bynum’s outstanding book, The Free State of Jones: Mississippi’s Longest Civil War, upon which the movie is largely based. (The book was recently re-released in paperback to commemorate the film’s release, and is also available in an audio edition read by none other than Mahershala Ali.)

The film’s main shortcoming may be its ability to reach a substantial audience. Also like Ride with the Devil before it, the potential is certainly there. Free State of Jones is packed with the right charge to breech the gates of our mainstream Civil War narrative. Only time will tell, however, if McConaughey’s star power, breakout performances from Ali and Mbatha-Raw, a haunting soundtrack, and excellent cinematography can light the fuse and trigger the popular explosion that Ride with the Devil could not.

As both a professional historian and a cinephile, I’ll confess that I’m rooting for the film. In the interest of full disclosure, I will also confess that when I viewed it, only three other patrons were in the theater. This is one of the few instances in which the writers, director, and producers of a film made a concerted effort to obey the historical script and actually pulled it off. So it would be a genuine shame for this “anti-Confederate experiment” on film to sink because critics don’t care for a story based on real sources and events, not just on how we’d like to imagine things turned out.

Matthew C. Hulbert is the author of The Ghosts of Guerrilla Memory: How Civil War Bushwhackers became Gunslingers in the American West (UGA, 2016) and co-editor of The Civil War Guerrilla: Unfolding the Black Flag in History, Memory, and Myth (UPK, 2015).