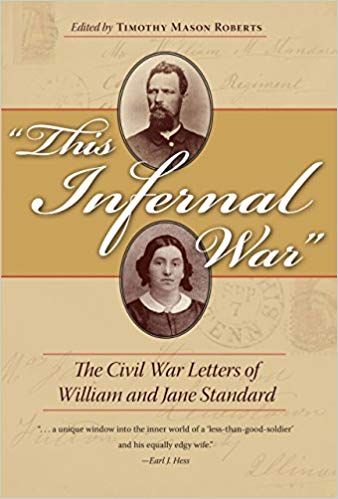

“This Infernal War”: The Civil War Letters of William and Jane Standard edited by Timothy Mason Roberts. Kent State University Press, 2018. Cloth, ISBN: 978-1606353356. $34.95.

The correspondence of William and Jane Standard is unusual in several respects. At age forty, William Standard was much older than the typical Union volunteer. Nor was he an enthusiastic soldier, and one can only wonder why he ever enlisted in the 103rd Illinois Infantry. Jane Standard shared her husband’s skeptical view of the war; having both sides of the correspondence not only amplifies that, but also offers important insights about their relationship and the connections between camp and home front. Both the Standards had much to say and expressed themselves in often tart language.

The correspondence of William and Jane Standard is unusual in several respects. At age forty, William Standard was much older than the typical Union volunteer. Nor was he an enthusiastic soldier, and one can only wonder why he ever enlisted in the 103rd Illinois Infantry. Jane Standard shared her husband’s skeptical view of the war; having both sides of the correspondence not only amplifies that, but also offers important insights about their relationship and the connections between camp and home front. Both the Standards had much to say and expressed themselves in often tart language.

From William, there were the usual comments about officers and his daily routine, and from Jane, there were immediate pleas for him to return home. “Get off if [you] can honorably. . . .Nobody knows anything about it but them that has the trial. I cannot live this way” (20). Many of her letters detailed hardships large and small. William in turn complained about habitual thievery among his comrades and later wrote of countless soldiers visiting prostitutes in occupied Savanah; nonetheless, like many an enlisted man, he believed that the common soldiers on both sides could easily negotiate a peace settlement. Often cynical, at one point, he deemed the war simply a “big speculation” (47). By early January 1863, he had given up on the Lincoln administration in part because it could not even pay the troops on time. His letters present vivid pictures of camp life including the sleeping arrangements, the unpalatable rations, and the peculiarities of his comrades. When it came to a soldier’s duty, William clearly relished foraging above all else.

Increasingly, William railed against both Lincoln and emancipation, hoping that northern Democrats would rise up to bring the war to an end. In early 1863, he forecast an avalanche of officer resignations that never took place. Jane agreed that Republicans simply “stay at home and talk big” (63). In February, a thoroughly disgusted William wrote: “It is more honorable to desert than to stay in this abolition war to free the niggers and [e]nslave the white man” (66). Jane suggested he conspire with a group of comrades to get captured, paroled, and then sent home. She did not necessarily want him to desert, but in early 1863 doubted the rebellion could be defeated. The couple worried about each other’s health and about paying taxes; occasionally, Jane took in boarders and later received assistance from the county.

William fought in the Vicksburg campaign, but Jane acerbically remarked that a local Republican celebration of the victory would have “their women and children out tonight to rejoice over the dead men and orphant [orphaned] children” (137). Both Standards judged the war through a partisan lens. William had grown “so disgusted with the army that I am not fit to keep company with anybody” (154). Despite his racial views, he briefly considered seeking a commission in an African American regiment. William even claimed that Republicans who enlisted in the army often turned Democrat after becoming disillusioned with how the war was being conducted. He soon decided, however, that War Democrats (who had turned into abolitionists) were little better than Republicans, and “all piss through the same quill” (189). Yet during the hard-fought Atlanta Campaign, his opinions shifted to some degree. Although he still deemed it folly for a young man to join the army, claimed that Lincoln intended to “kill off all the northern men and boys” (210) and southern white people just to free the slaves, and favored George B. McClellan in the presidential election, he grudgingly admitted to being a “very good abolitionist while I am in the army” (219). The Standards remained staunch opponents of the Republican administration. Jane even begrudged the local celebrations over the news of Lee’s surrender and, after Lincoln’s assassination, could only think of all the men the president had sent to their deaths.

Editor Timothy Roberts deserves high marks. The concise introduction sets the stage well for the documents that follow; the annotations for the letters are thorough and helpful. The volume has a fine index not only of individuals but of subjects—a feature often deficient or even absent in such edited volumes. Altogether, This Infernal War makes for good reading, and researchers will find it equally rewarding.

George C. Rable, the author of numerous books, is Professor of History, Emeritus at the University of Alabama.