As a youngster, I visited Shiloh National Military Park on a number of occasions. Given my fondness for artillery, it should be no surprise that the “Ruggles Battery” tour stop was always my favorite; I visited the interpretive stand at that tour stop countless times. This marker that orients visitors there is decades old and due for replacement (if not replaced already). The new look will reflect changes to the way historians interpret that particular episode in the battle of Shiloh, calling into question the number of cannons involved in the battle and their impact on its outcome.

For me, the marker is like a milepost in my understanding of the battle. Things I “knew” about Ruggles Battery are anchored to my formative experience on the battlefield. Today, everything I “know” about Ruggles Battery is a refinement of ideas gathered along an intellectual path away from that milepost.

Beyond my personal experience, Ruggles Battery is an example where our collective understanding of the particulars of a battle have changed over time. The “story” receives fresh updates as historians assimilate new information and reassess old assumptions.

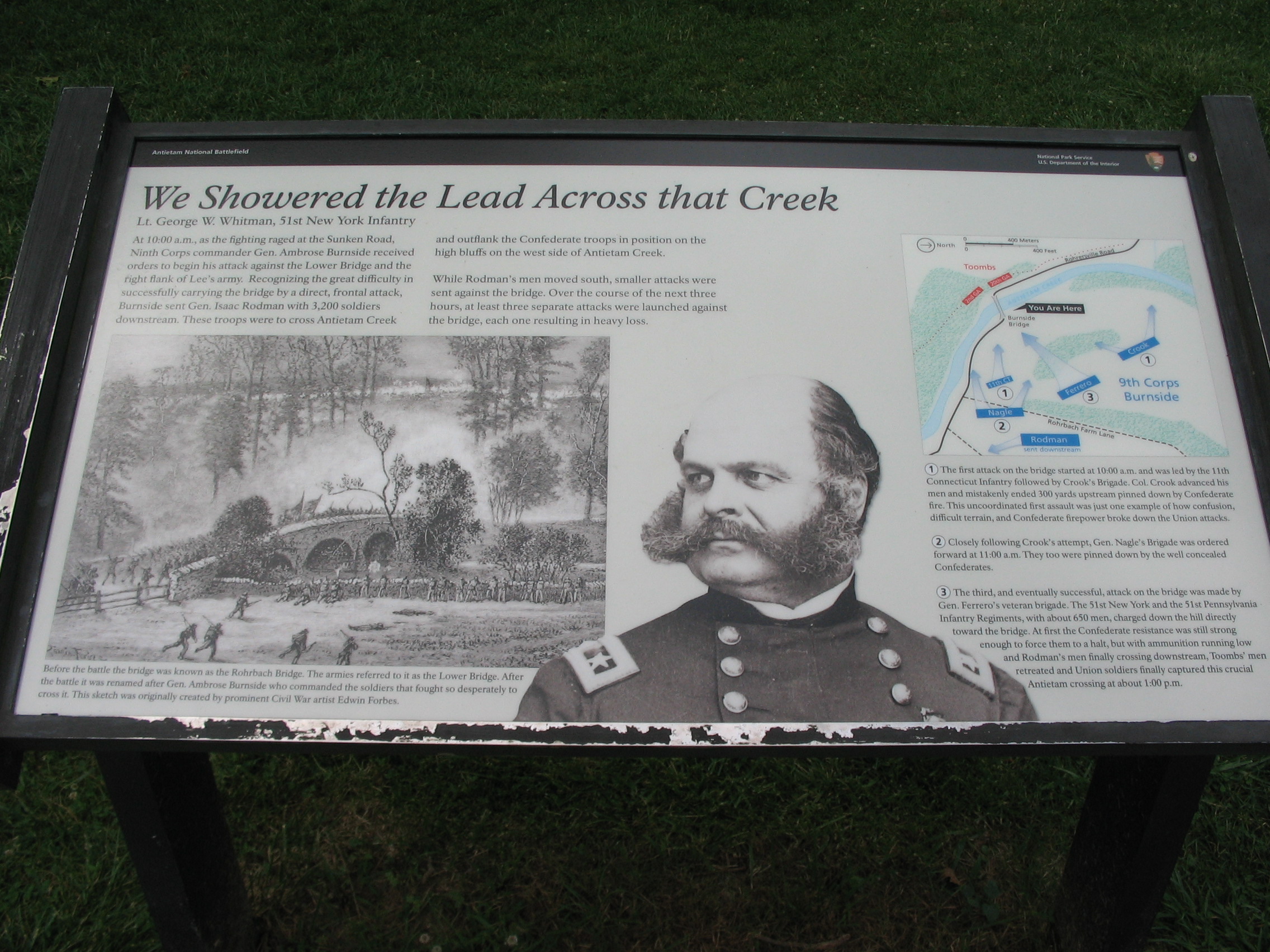

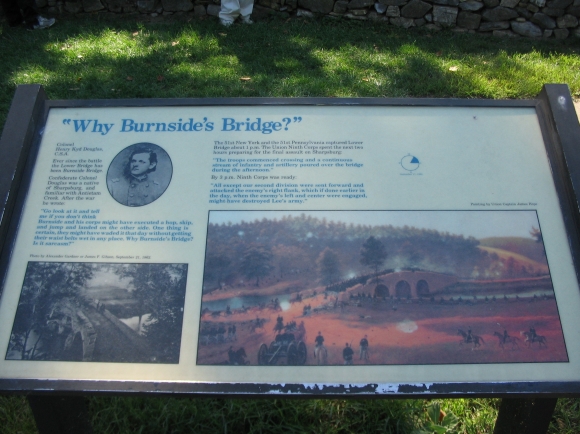

The Antietam battlefield offers another example of such change, though on broader scale. As historians studied the flow of that battle in more detail, their conclusions strained the long standing “morning, mid-day, and afternoon phases” timeline of the battle. Dutifully, the park staff began updating the public interpretation several years ago. Now the wayside interpretation for Burnside Bridge begins framing activity at the lower bridge in relation to other actions on September 17, 1862. Instead of bluntly criticizing Burnside’s tactical execution, the narrative notes that the assaults on the bridge were supporting a larger flanking movement downstream. And a colored map helps explain the sequence of events and why initial assaults failed.

The tone of this new marker stands in contrast to the wayside it replaced.

No longer does Henry Kyd Douglas chide Burnside. We’ve waded into Antietam Creek ourselves, literally and figuratively, and discovered the answer to the question posed by Douglas those many years ago.

Similar updates to other battlefield parks bring today’s visitor a more accurate appreciation of historical events. Some will certainly complain that the refreshed interpretation diminishes the “old story,” perhaps turning the battle’s narrative into a less familiar, and potentially less romantic, measure. For example, Burnside’s obsession for a dry crossing of a small creek is no longer seen as a ghastly mistake. And the same general’s repeated attacks on Marye’s Heights are removed from tactical isolation and seen in the broader context of the Fredericksburg battlefield. Massed artillery at Shiloh is no longer some invincible force that crushed a salient. And so on…. It is not that Douglas’ “hop, skip, and jump” are tossed aside. Rather, it becomes a block in a sturdier structure that better represents the whole.

Ultimately, the discipline of history is in many ways a quest for closer, finer definitions. The more we know, the better we know (or is it vice versa?).

Craig Swain is a consultant from Virginia but is a native Missourian. His background includes a degree in history and service in the Army. Craig’s focus is the study of Civil War Artillery, which you can read about on his blog—To the Sound of the Guns.

Photos from author’s collection.