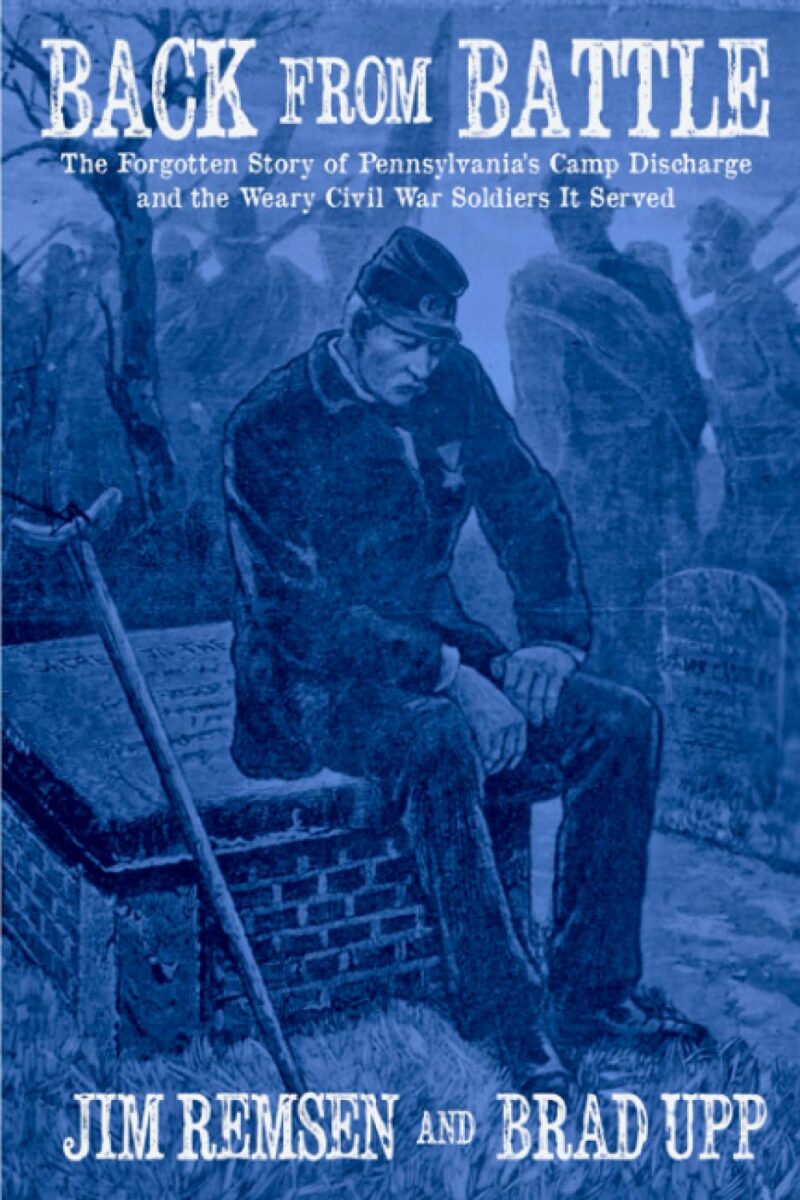

“Camp Discharge never got its monument,” writes Jim Remsen. “If it weren’t for the military records, memoirs, and news clippings, one could think the place never existed.”

Fortunately for the military post near modern Gladwyne, Pennsylvania, and for the personnel stationed there from 1864 to 1866, Back from Battle provides readers with evidence that “the place” did exist—and that it performed a valuable role in the conflict’s final months and immediate aftermath.

In the summer of 1864, the U.S. War Department authorized the establishment of temporary barracks “in the vicinity of Philadelphia” to accommodate 2,000 men. The “new camp…was set up not to muster in and train reinforcements to join the hot war,” but rather “to reduce ranks—to muster a particular set of Union soldiers out of the service.” According to Remsen, “the camp carried out an essential function processing a particular category of Pennsylvania volunteers—castaways…who had become separated from their regiments due to capture, injury, or other grim happenstances of war.”

By the end of 1865, more than 800,000 soldiers mustered out of federal service; about 1,100 of them passed through Camp Discharge, including nearly 500 former captives held in Confederate military prisons. At an initial cost of $61,000 (about $1.1 million today), the facility boasted a headquarters, officers’ quarters, hospital, barracks, water distribution system, stables, latrines, and storehouses for both commissaries and a quartermaster. One newspaper noted that the camp was intentionally placed on a “high and airy” hill several miles from Philadelphia proper, owing to persistent smallpox outbreaks in what was then the second-most populous city in the U.S.

Throughout Back from Battle, the authors effectively utilize the Camp Discharge story to highlight bigger-picture themes of the Civil War era, including bureaucratic frictions, medicine, desertion, the prisoner of war experience, and veterans’ attempts to forge memories of the conflict.

A dozen men per day sought aid at the camp’s hospital, which hit a daily record of 87 patients. Hundreds of soldiers ailed from airborne diseases, skin infections, and gastrointestinal illnesses. One soldier confided, “I am more dead than alive after all my trials of suffering and hardships.” Another lost his sight and was later committed to a state mental hospital.

The camp experienced its share of controversies, including a scandal between Hancock and a subordinate officer over a construction project. Some soldiers begged to go home, insisting they were being held in army service beyond the terms of their enlistments. Others alleged that the commanding officers were “constantly drunk.” At a New Year’s Eve celebration, an infantry soldier wounded five times on the battlefields suffered an accidental gunshot wound. On another occasion, a nearby train accident caused a fire in the camp.

In addition to their primary narrative, Remsen and Upp provide a host of valuable resources, including dozens of images and portraits, separate panels that vignette individuals, and a 120-page roster identifying the names and units of Camp Discharge’s soldiers: 1,119 troops from 89 Pennsylvania regiments, and 644 soldiers from three regiments who served as garrison guards. One chapter by Upp reveals the story of the facility’s discovery and his personal archaeological and research efforts.

The authors also inform readers about how they may see traces of the site today. “All the familiar symptoms of a once-bustling Army post are present if you look hard enough,” writes Bradd Upp. Fortunately, thanks to his and Jim Remsen’s thoroughly researched and movingly written Back from Battle, interested Civil War aficionados now have a resource to help them do so.

Codie Eash serves as Director of Education and Museum Operations at Seminary Ridge Museum and Education Center in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. He operates the independent Facebook blog “Codie Eash – Writer and Historian” and is a founding contributor to PennCivilWar.com.