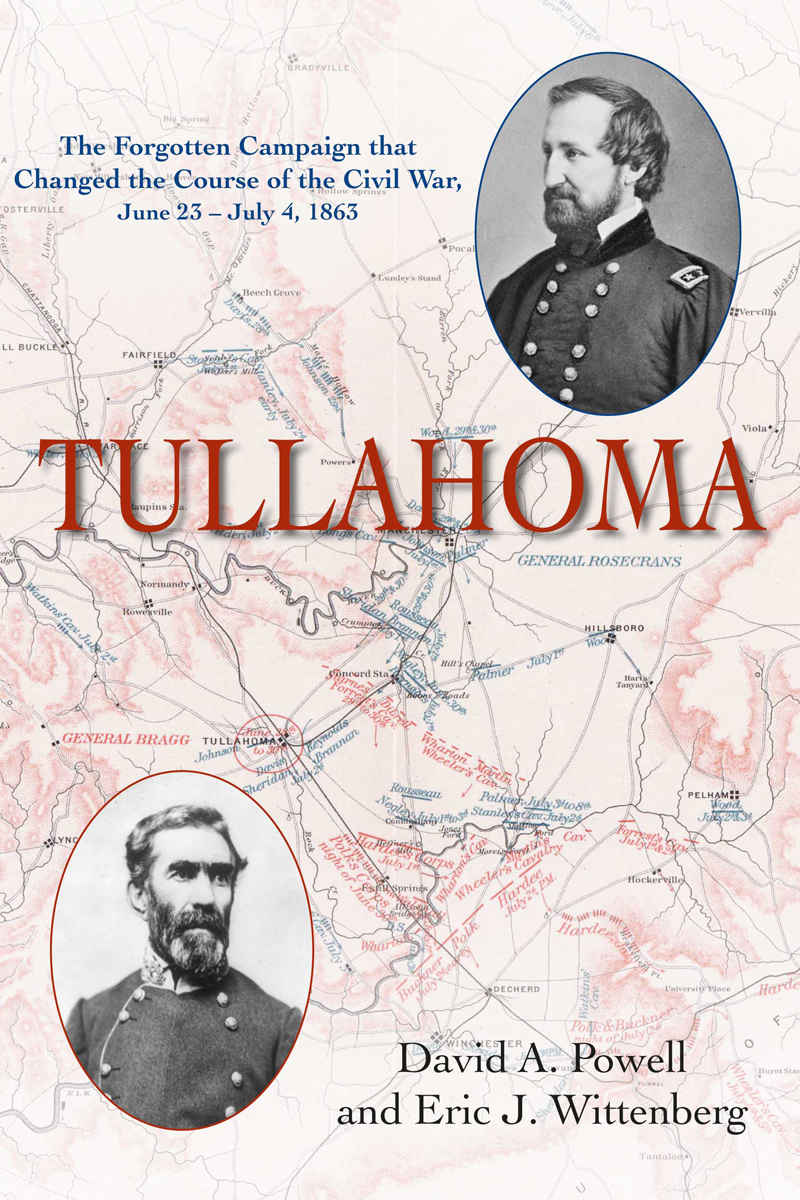

The diligent, robust scholarship found on the pages of Tullahoma: The Forgotten Campaign that Challenged the Course of the Civil War, June 23 – July 4, 1863 has not only expanded the range of historiography pertaining to that perennially relevant subject—the Civil War—but helped to further balance perspectives on the relative importance of the Western Theater. From the outset, authors David A. Powell and Eric J. Wittenberg provide understandably positive recognition to the outstanding achievements of Federal armies in July 1863 relative to their victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg, but they quickly pivot and assert that “the war was not confined to Pennsylvania and Mississippi” (ix).

In redirecting their focus toward the Tullahoma Campaign—i.e., the struggle to determine whether or not the Union or Confederacy would control Middle Tennessee—and through their subsequent, detailed explanations of that campaign’s challenges and overall strategic importance, the authors demonstrate that the war out west was more than just a hinterland backdrop to the stellar accomplishments of Meade and Grant. If anything, the significance of the Union’s eastern victories was underscored by the success of General William S. Rosecrans and his Army of the Cumberland during the same period.

An outstanding example of the authors’ skills as researchers, writers, and expositors of historical information is exemplified by the manner in which they emphasize the critical nature of the Tullahoma Campaign without bemoaning the deficit of such detailed examinations in Civil War scholarship. Taking the Tullahoma Campaign on its own terms as a critical turning point in the Civil War, the authors delve into the myriad factors that directly impacted the campaign’s outcome, especially the quality of the northern and southern commanders.

The biographical backgrounds pertaining to Union General William S. Rosecrans and Confederate General Braxton Bragg are rendered with such captivating description and analysis that their subsequent actions during the contest are quickly understood for the specific influences their respective strengths and weaknesses had upon the Tullahoma Campaign. While possessing talents that helped elevate them to command, Rosecrans and Bragg were also burdened by deep flaws that often neutralized the benefits of their gifts. This was displayed most prominently in the ability of both men to earn the hostility of senior officials in their respective chains of command.

For Rosecrans, imperiously demanding that the Army of the Cumberland’s supply needs be prioritized over other commands steadily diminished the patience of General Henry W. Halleck, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, and even President Abraham Lincoln. The Union’s military and political leadership had already been vexed by self-important subordinates like, for example, General George B. McClellan, so similar behaviors from Rosecrans generated a negative “turning point in the relationship between Rosecrans and Washington” (28). The authors further note that “Rosecrans, ever politically tone-deaf, failed to understand why his relationship with the government seemed to be deteriorating.” (28).

While Rosecrans surely possessed his share of interpersonal defects, Confederate General Braxton Bragg proved himself even more inept in personal relations. His generally disagreeable personality was exacerbated by his persistently poor health, his basic inability to “get along with people he disliked,” and his utter failure in winning the “loyalty of his chief lieutenants” (48). As one of Bragg’s subordinates put it, the General’s “‘manner made him malignant enemies and callous, indifferent friends’” (48).

Nevertheless, in a testament to the thoroughness of their research and commitment to a professional, rigorous analyses of the evidence, the authors take time to highlight the strengths that made Bragg such a good choice to command the Army of Tennessee. Their challenging the historiographical trend that has generally summarized Bragg as an overall failure sends an alert and challenge for historians to beware of being passively swept into currents of popular perspective and, likewise, to boldly take differing positions on a subject when armed with sufficient evidence. Recent scholarship on the presidency of Ulysses S. Grant like Charles Calhoun’s The Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant (University Press of Kansas, 2017) and the more popular Grant (Penguin Books, 2018) by Ron Chernow, both illuminating the actions of Grant to ensure that African Americans did not lose during Reconstruction the civil rights won during the Civil War, underscores the point that there is always more research waiting and more revelations to discover about the people, events, and eras of the past.

Along with its many narrative strengths, the information in Tullahoma sits on a massive foundation of facts that are drawn from sources like the Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, diaries, newspapers, manuscript collections, letter collections, historical societies, newspapers, and an impressive array of secondary publications. Such a treasure of resources leaves no doubt that the authors spared no effort to produce a top-quality work.

Mercifully, the authors use of military terminology is done in a selective, judicious manner that prevents the narrative from being overwhelmed by jargon. They also smoothly make the point that, as was the case with Antietam, which gave Lincoln the political room to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, and Gettysburg and Vicksburg, which boosted Lincoln’s fortunes heading into the 1864 presidential election, the Union’s Tullahoma Campaign victory was a major, positive variable affecting the political equation for Lincoln’s administration. Conversely, the setback for the Confederacy moved some of Bragg’s lieutenants to attempt his removal, which “bordered on near mutiny” (319). The crisis in the ranks paralleled the dimmed outlook for the Confederacy’s survival. In sum, authors David A. Powell and Eric J. Wittenberg provide a compelling narrative that explains the critical significance of the Union’s Tullahoma Campaign victory, which helped put the Confederacy—and, with it, the vile system of slavery for which it fought—on a path toward ultimate extinction.

Fred L. Johnson III is an Associate Professor at Hope College in Holland, Michigan. He is currently working on General Robert E. Lee’s Priority Target: The Baltimore & Ohio Railroad.