Our host, John Heckman, talks to historian Cecily Zander about the challenges Robert E. Lee and his vaunted Army of Northern Virginia encountered when facing a new opponent in Ulysses S. Grant during the summer of 1864.

Our host, John Heckman, talks to historian Cecily Zander about the challenges Robert E. Lee and his vaunted Army of Northern Virginia encountered when facing a new opponent in Ulysses S. Grant during the summer of 1864.

John Heckman: Can you let us know a little bit about what the Army of Northern Virginia looked like in 1864? How is it different from previous years?

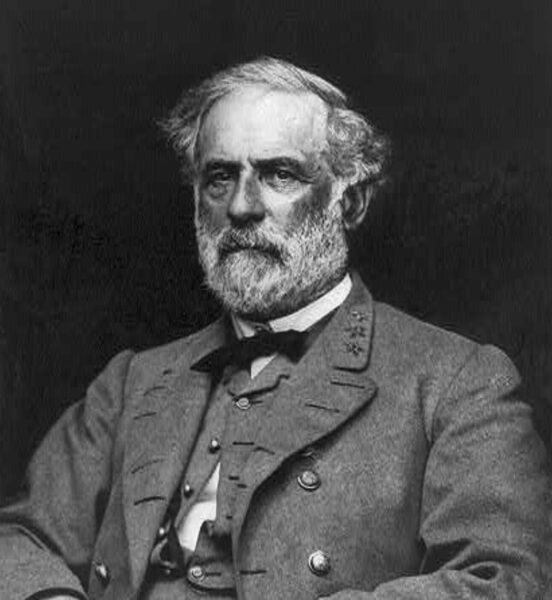

Cecily Zander: I think with all things Civil War we can go back to the summer of 1863. Robert E. Lee and his army experience a defeat at Gettysburg and they retreat. But Lee leaves Pennsylvania feeling quite confident that he’s dealt a measurable blow to the Army of the Potomac.

He says to some of his subordinates that army will be as quiet as a sucking dove for three months. It’s actually not until the following May that they fight a major battle at the opening shots of the Overland Campaign. So, Lee basically has from the end of the Battle of Gettysburg and his retreat till the beginning of May 1864 to reconstitute and reorganize this Army of Northern Virginia, which is now functioning around this nucleus of three corps, which it was reorganized into from its two-wing structure after the death of Stonewall Jackson. And those core commanders are our same familiar faces from Gettysburg.

Library of Congress

Library of CongressRobert E. Lee

We have James Longstreet, we have Richard Ewell, and we have A.P. Hill. And Jeb Stuart, of course, in command of Lee’s cavalry, though we know that Jeb Stuart comes out of Gettysburg a little bit tarnished, a little bit lower in the estimation of Lee than he had been maybe going into the campaign. But I think Lee and his army are feeling quite confident.

They’ve never yet faced a Union army commander who seemed willing to pursue them beyond a single battle. Of course, we know this is going to change in the beginning of May 1864. I think one really interesting thing for us to talk about is the kind of psychological difference of the warfare Lee’s army is about to face when you’re under constant fire for a period of six weeks when that’s never been the experience of this war.

It’s probably one of the first times in human history where soldiers have been under that kind of strain of battle for that extended a period of time. It’s going to strain commanders as well. We know stories of commanders on both sides breaking under this pressure. But I think Lee has reason to feel confident.

His army stands at about 60,000 to 65,000 troops across those three wings and his cavalry. Of course, he’s going to be outnumbered at various points in the campaign that follows, almost two to one. On paper, the Union army is going to number 120,000 men. And for Lee, he’s going to have a new adversary.

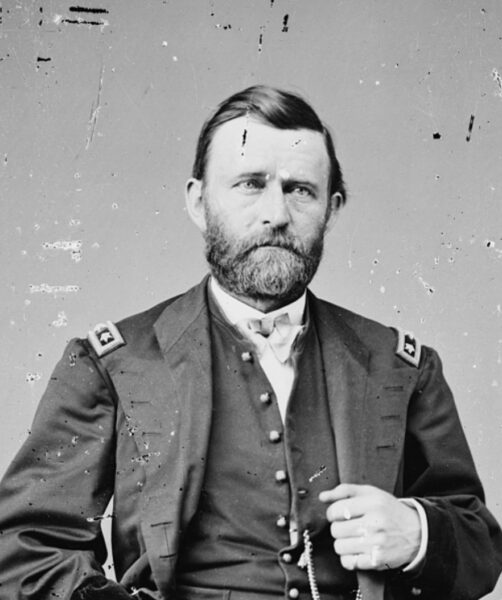

Of course, George Gordon Meade is going to maintain, or retain, command of the Army of the Potomac. But in the late winter and early January 1864, discussions in the War Department in Washington result in Ulysses S. Grant being called from the West, where he’s just dealt a quite embarrassing blow to Braxton Bragg in the battles for Chattanooga, to take command of all Union armies.

And Grant is going to decide, rather than sit in Washington, he’s going to join the Army of the Potomac in the field. He knows he needs to operate alongside the principal Union army against the most important Confederate army, which is Lee’s army for various strategic and tactical reasons, but also for really political and social ones.

We know that by this point in the war, Confederate national identity and the Army of Northern Virginia are almost synonymous. The Army of Northern Virginia’s success is Confederate success, and Lee is the avatar for Confederate nationhood. And so, as long as Lee is in the field, the Confederates have a great deal of hope.

But Lee is also 57 years old. And he’s going to be constantly campaigning with this army. I’m fortunate not to be there yet, but I cannot imagine the aches and pains, the rheumatism, and we know that for a good bunch of this campaign, Lee is not going to feel his best, nor are Richard Ewell nor A.P. Hill. James Longstreet is going to be wounded early on.

The army is maybe starting to feel the effects of a war stretching into its third year. And the pincer movement that they’re facing. Grant’s goal, of course, to pin lee as close as he can to Richmond, ideally in a siege like the kind that had worked so well at Vicksburg, is underway, and Lee knows that the last thing he can do, or the last thing he wants to do for his army, is to be settled into a siege near Richmond. Because he knows that at that point you can start the clock. It’s only a matter of time waiting it out.

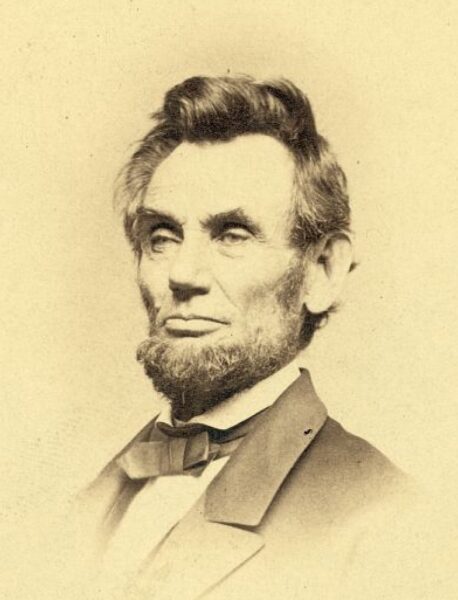

Lee’s mainly hopeful in the summer of 1864 that if he can hold out against Grant, it could have a major effect on the elections for the president in November in the United States. And so, I think in the back of Lee’s mind, he’s always attuned to this. The longer he can hold out, as long as he doesn’t give Grant any major victories, the worse it is for Lincoln.

And maybe if Lincoln doesn’t get reelected and George McClellan does, McClellan sues for peace and the Confederacy wins its independence. And so, the stakes are pretty high. And we should always remember that Lee is very well aware of those politics and that’s one thing that he’s trying to manage in how he conducts his campaign against Grant. That was long-winded but that gives you a sense of what’s going on as we enter the spring and summer of 1864, probably one of the most consequential periods of the Army Northern Virginia’s existence, but really in the Civil War bar none.

John Heckman: Do you think that action of defending at Petersburg, settling in for this siege, do you think that’s Lee’s way of a delaying action, just to see what happens in November? Because it’s like the last gasp of trying to win this war in a certain way, and if they can hold out and stall, then maybe they can survive.

Cecily Zander: Yeah, Lee always understands this, and he says it to his subordinates. We just need to convince the northern populace this war isn’t worth fighting. And the way we do that is by holding out. We just have to break their resolve. And until William Tecumseh Sherman really has his breakthrough in Atlanta, it’s not really looking great for Lincoln at all.

That’s when Lincoln writes his famous letter, right? It’s in the midst of the siege of Petersburg, Lincoln writes his note to his cabinet. It says, we’re going to lose the election. So, really, Lee was doing everything right. For Lee in terms of his personality and his inclination, settling into a siege is 180 degrees from what he would like to do.

We know he’s one of the most aggressive commanders in the war. He’s often aggressive with a much smaller army, which is very, very risky, but it seems to pay off for him time and time again. So, he’s going against instinct and inclination in doing that, but I think you’re exactly right. The reason he’s doing it is he’s playing the political game.

And if not for William Tecumseh Sherman and Lee’s archnemesis and opposite number, Joe Johnston, agreeing basically to retreat into the defenses of Atlanta as Sherman approaches him, it might’ve worked. But there was no equivalent commander to Lee in the West who could prevent Sherman’s conquering of Georgia and the Carolinas.

And that’s ultimately what turns the tide for Lincoln.

John Heckman: What’s Lee’s standpoint on his new adversary coming East? Does he say anything about it? Does he write anything about it to others? What does he think?

Cecily Zander: You know, not really. Lee and Grant are so funny. They almost never acknowledge each other, either in their wartime writings or their postbellum writings. We know at Appomattox, Grant has a memory where he thought he’d been so junior to Lee in the Mexican War, he wasn’t sure Lee remembered him. I don’t think Lee fears any Union commander. He doesn’t really have a reason to. The one that gets under his skin the most, for whatever reason, is John Pope.

Library of Congress

Library of CongressUlysses S. Grant

He really, really is bothered by Pope. He calls Pope a miscreant, which in 19th century parlance is like a really, really insulting thing to be called. Because Pope was political, and Pope went after Confederate property and Confederate civilians, and this really upset Lee, especially because Pope was operating in Virginia in the summer of 1862.

He doesn’t see Grant that way. He doesn’t write about Grant in those terms. And again, he doesn’t know yet exactly what Grant’s going to do. That’s all going to hinge on the final hours of the Battle of the Wilderness, when the action slows and Grant is approaching the Orange Plank Road and the entire Union army is watching him to see if he will turn and continue south toward where they know Lee has withdrawn, or whether he’s going to turn and retreat.

And the question is equal on the Confederate side. Is Grant going to keep fighting? After the Wilderness, I think Lee knows that Grant is coming for him. He’s not going to give up. So, he’s facing a different kind of animal. But after the war they still won’t really acknowledge each other.

These two great commanders, they have their couple of interactions at Appomattox and that’s about it. Neither one of them could ever fully admit that they were each other’s greatest rival, which is really funny. And people love to debate that question. Who was the better military genius or who was the better commander?

It depends on what you value. It depends on what your criteria are for assessing that. But I think we could agree that they are the two great commanders of the war. They are the greatest of their respective sides at the very least, and it is their titanic clash that will decide the outcome of the conflict.

No offense to Joe Johnston and William Tecumseh Sherman, who are going to have their several tête-à-têtes as they march toward 1865, but it’s not the same kind of weight of circumstance that is the one that Grant and Lee are going to play out over this period.

John Heckman: You mentioned how Lee’s the avatar for the Confederate experience and the Confederate war effort. And when he gets involved in this siege at this time in 1864, as you said, it’s 180 degrees different from where he wants to be. He wants to be maneuvering and fainting and doing all kinds of stuff to try to throw off his enemy.

How does that leadership style influence the morale of the army when all of a sudden, the commander who wants to break out and scurry around the flank and do those kinds of movements is now bogged down in this siege to buy time to see what happens in the future?

Cecily Zander: I think in terms of morale, the Confederacy still believes in the Army of Northern Virginia.

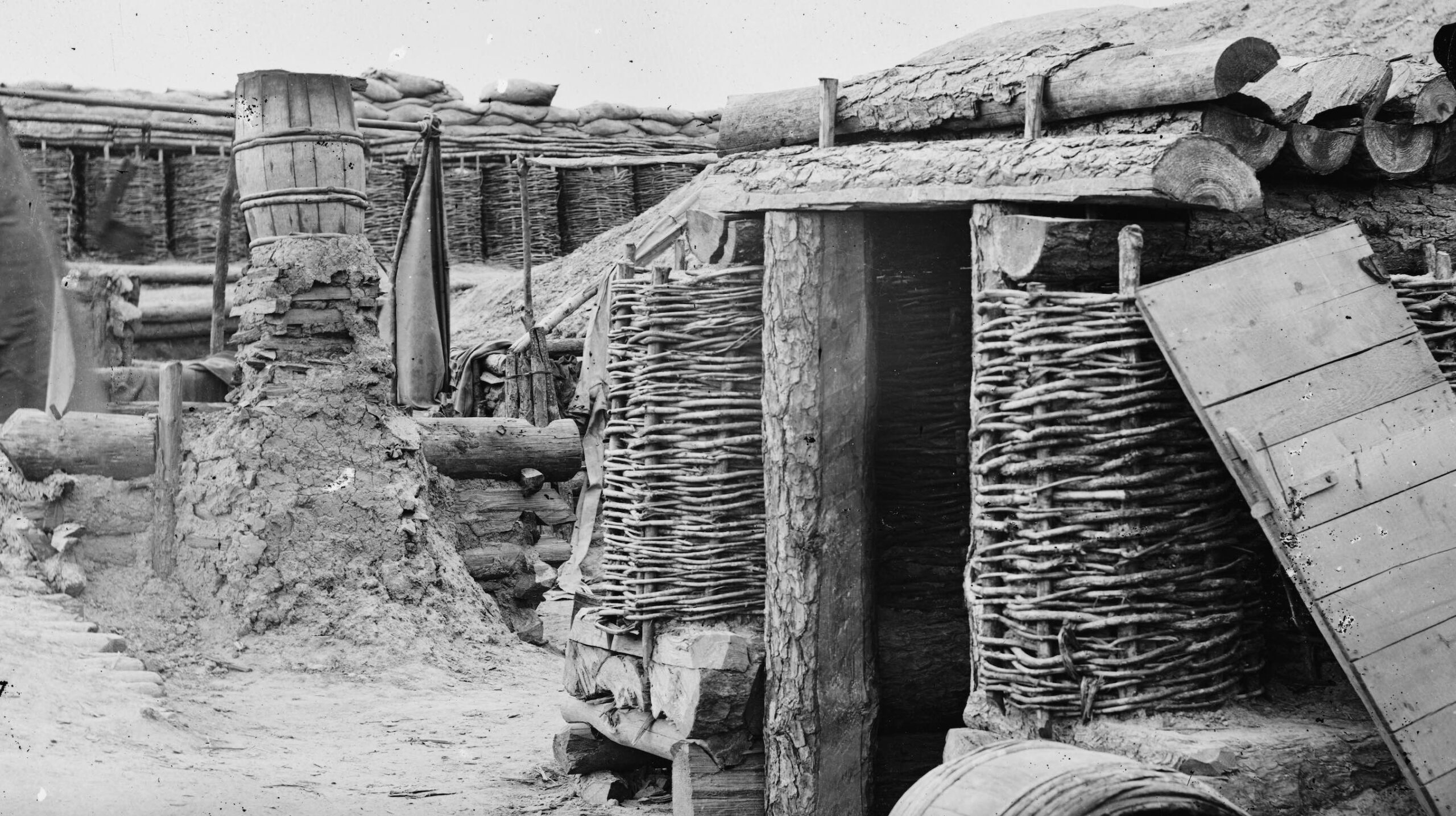

If you look at southern newspapers, if you look at civilian correspondents, it’s like they expect that he’s planning something, like some great breakout or some strategy. I think what you see actually in the trenches, which we know are literally trenches by this point in the siege of Petersburg, you start to see the slow leaking of men away from the army when it is not actively moving and maneuvering through the field.

Sitting in this siege becomes very hard for a lot of rank-and-file Confederate soldiers. We should remember that by 1864, if you were in a gray uniform, you were not getting out of a gray uniform. They were also increasing conscription to include everyone from the age of 17 to the age of 50 because they were losing so many men from the ranks.

About one in two soldiers in Lee’s army are going to become casualties during the Overland Campaign, so before they even get to Petersburg. So, Lee needs to refill his ranks. So, in some ways, the siege is good because it gives him a chance and time to bring men up and refill his army, or let those who were wounded or injured recover.

But fewer men are going to be given furloughs or allowed to go home, and that’s going to become increasingly hard. And so, on the flight to Appomattox, we know that huge numbers of Lee’s troops just walk away. The army just melts away, and that’s 1865, of course, but I think it tells you what’s happening, is this slow realization that as much as everyone expected Lee to have this great plan to break out of the siege, he was right when he predicted that if it gets to a siege, that’s the end. Because he knew as well as anyone Grant had him outnumbered and Grant had a resource advantage that Lee simply couldn’t match. And all Grant had to do was be patient, work that line out toward Appomattox, and fully surround the army and give them really no chance.

And then Lee is not willing to condone or sign off on a guerrilla conflict. And so, I think that tells you something too. Lee wanted to win in a regular fashion on a battlefield. He didn’t want to win in a subversive, guerrilla way. And so, I think you look at men in the ranks, they don’t lose belief in Lee but I think they can see the writing on the wall as the summer of 1864 turns to fall and there’s not really much movement.

You have these pieces like at Fort Steadman or in the Crater, but it’s not the kind of fighting you’d expect. And Confederate soldiers don’t have any choice. They’re stuck. They can’t go home. And it’s become really hard on wives and children at home. We know lots of men leave the ranks and come back because they go help get the crops in, they go down to North Carolina to their farm, they take in the crops and they come back. But we have these weird numbers over the course of this campaign. Portions of the army just seem to disappear for a period of time. And I think it’s getting increasingly hard on Confederates to sustain that individual belief and that waning of the army, that siphoning off of troops tells us that.

But again, I don’t think that’s about Lee. I think that’s just about a broader malaise that’s setting in when the war goes from these great climactic battles to this quite boring, on a day-to-day basis, siege that seems like it’s going to go on forever.

Because it’s a very slow process, this nine-month siege of Petersburg. It just must’ve been the most boring three-quarters of a year that they ever lived through.

Library of Congress

Library of CongressAn interior view of Confederate works built during the Siege of Petersburg.

John Heckman: Can you speak about the home front and the fact that we think of the postwar view of the Army of Northern Virginia as this unbeatable force. We don’t think about the idea that it was seen as almost magical in 1863–1864, as in, oh, that was a setback, but we’re still going to find a way out because this army cannot be beaten. How is that seen on the home front, when these men are receiving letters from wives who are saying, hey, I’m on the farm by myself and we need to take care of this crop, or we need to take care of these children. How is that seen in the press and other places where they’re like, oh, Lee has to have a plan to break out? They keep saying this.

Cecily Zander: Yeah, it’s a great question. It’s something we forget. The field of Civil War history is so wonderful because you can write about anything you want. You can write about military topics and you can write about social topics.

And we have things in 1864 like the Richmond Bread Riots, which show you how much dissent there is on the home front and how desperate people are getting because prices are rising and there aren’t any crops and you can’t get bread. But Lee is still in the field. That’s the thing they always come back to, is the war’s not over, and if we have to bear this strain so that dad or brother can stay in the ranks, we’re going to do that, because they’re part of the chief instrument for Confederate independence. And so, the burden that Confederate civilians are willing to bear is immense.

And, of course, you see this throughout 1864 in the fact that William Tecumseh Sherman expected his campaign through Georgia to break the back of the Confederacy in terms of the civilian morale. And people like Jacqueline Glass Campbell have written about this. It actually galvanized Confederates. It made their belief even stronger that they could win the war. They respond to these hardships coming back and saying, we can still do this because the Army of Northern Virginia has really never been defeated, at least as they see it. Antietam is a half defeat because they retreat safely.

Gettysburg the same. So even though those battles end with the Union army in control of the battlefield and therefore Union victory, the Army of Northern Virginia does not suffer the reputation of being an army that’s constantly being defeated. Certainly not in the same way Braxton Bragg’s army suffers that reputation.

Because even when Braxton Bragg wins a battle, and that’s singular, the only battle he won at Chickamauga, he fails to control the city. And therefore, it’s still seen as not fully a victory. Whereas all of Lee’s defeats are almost spun as victories. And it tells you how different the rhetoric that surrounds Lee is. And I think what civilians show you is, if this is the burden we have to bear to keep Lee’s army in the field, to keep the Army of Northern Virginia in the field, we’re going to do it. And we’re going to funnel support away sometimes from other Confederate armies—to the great frustration of other commanders like Joseph Johnson and Braxton Bragg—to the Army of Northern Virginia.

We’re going to give Lee the best personnel. We’re going to send the Daniel Harvey Hills and the Leonidas Polks out to the West. They’re not going to help us in Virginia. Virginia is our focus. Virginia is where the war is going to be either won or lost. And so, we need to funnel our resources and support to Lee.

And so, the answer to that question is, we’ll bear everything that we have to, to do this. And they really look to the revolutionary legacy in that regard. Again, how did the Patriots win their independence? That’s the kind of war the Confederates see themselves as fighting. So, you can’t give up the morale. You just have to outlast the will of those who would otherwise be your conquerors or oppose your independence. And so, they’re also always hearkening back to that. This is, maybe Lee at Petersburg moment is Washington at Valley Forge. What can we do in this moment to galvanize this army?

And they try to do it. They send everything they can to the trenches. Socks, food, water, everything that they can give to this army. Because, it needs to be the army that wins. And if they can defeat Grant, they’re going to win the war. That’s the bottom line for them. That’s the belief. And it’s hard for us to realize the degree to which the Confederacy did imbibe that sense of nationhood. That they already were a nation, that they were fighting to establish an independent nation that would be equal in its reputation and fame to the United States.

We don’t like to talk about this kind of exceptionalism, but they truly did believe they were exceptional, and one of the reasons for that was Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia.

John Heckman: It really reminds me of the arguments that we still have at every conference or every time two Civil War historians get together about which theater was the most important.

And it seems like that discussion was already starting in ’63, ’64, ’65, where it’s like, we need to make sure the ANV stays alive. Grant coming east, things like that. Some people, they don’t want the answer to be like that. But for people like me who think the eastern theater is the important one, we have primary sources to back that up right?

Library of Congress

Library of CongressAbraham Lincoln in 1864

Cecily Zander: Well, Lincoln tells you it. He’s going crazy in the summer of ’62–’63 when Union armies are just absolutely destroying the Confederates out West. And it’s not being written about in the international press. The British and the French are still having conversations about recognizing the Confederacy as a nation.

And Lincoln’s like, why does a half defeat in Maryland hurt us so much when all of these victories out West seem to amount to nothing? So, you also have the international component. The eyes of London and Paris and Berlin were focused on what’s going on in Virginia.

It’s got the two capitals. It’s got the most important armies. Every commander of note has his shot there. Yeah, it’s absolutely true. And when we say that, I think people get really upset because they’re like, you’re ignoring these other theaters. Absolutely not. Grant doesn’t end up in Virginia without the record of victories he establishes in the West.

The West does matter. It creates U.S. Grant. It creates William Tecumseh Sherman. But if you were actually going to say, where was the outcome of the war decided, it’s in the trenches around Petersburg in the summer of 1864. Because Confederates did not attach their national identity to Braxton Bragg. They were never going to do that. They attached their sense of national identity to Robert E. Lee. And, therefore, what Lee did mattered far more than what any other Confederate commander did.

An interesting counterfactual: What if Albert Sidney Johnston lives to continue to command armies in the West? Would he have had the same kind of love because he was at least as capable as a military officer? Possibly. But Lee also has the connection to George Washington. He has the status of being one of Virginia’s first families and he doesn’t lose and he’s aggressive. And that’s what the Confederates want to see because they have a series of other generals who really love to retreat.

And, when you’re an army, you’re the underdog, and you’re fighting, you want to see that tenacity. And so I think Lee, in terms of his personality, suits the idea that this is an upstart nation fighting for its survival. That aggression, that willingness to take a gamble and see it pay off.

It makes a lot of sense why it’s Lee over anyone else that Confederates attach their identity to. And therefore Virginia, the eastern theater, really has to be the most important theater in determining the outcome of the war.

John Heckman: There’s another episode on this series where we discuss Johnston and Hood. And I always thought Joe Johnston was so kicked to the side in a way because he’s not that aggressive Lee type. And Lee obviously takes over for Johnston. What is their relationship like, at least in correspondence with each other, especially at this time where they’re in a do or die now. This is it. And one’s dealing with Sherman and one’s dealing with Grant.

Cecily Zander: It’s really interesting. They’re mirror figures in so many ways. They’re very close in age. Both Virginia gentlemen upbringings, slaveholding families, very high ranking. Joe Johnston was the highest-ranking general who defected to join the Confederacy, which is why he thought he should have been the highest-ranking Confederate general at the beginning of the war. And he ended up like third on the list and that was really galling to him. And he and Jefferson Davis didn’t get along. Lee and Davis can work together. That’s another thing that sets Lee apart is that Lee can work with Davis. And Davis trusts Lee. Davis never trusts Joe Johnston. Lee and Johnston have to work together.

I think Johnston gets knocked in the Atlanta Campaign for not standing up to Sherman more. But I think Johnston actually fought the smartest campaign he ever conceived of during the war. Because his idea is really the same as Lee there. We’re trying to delay these Union victories until after the election.

So, Johnston is retreating this way into Atlanta. Lee’s retreating down here into Petersburg. They’re mirroring each other in some ways. It’s just that Johnston actually avoids set-piece battles that destroy his army, whereas Lee fights at the Wilderness, in Spotsylvania, and Cold Harbor and ends up with half his army becoming casualties.

I think Johnston actually fights the smarter, better battle if you’re looking at which one of these is preserving Confederate resources, but they’re operating on this same idea and they’re in that together. They’re colluding in that. We need to make sure that we don’t give the Union civilians any reason before the second week of November 1864 to reelect Abraham Lincoln.

So how can we do this? And it’s one place where Johnston’s tendency to retreat actually works out really well. But because that’s his reputation by the time they get in and around Atlanta, Jefferson Davis becomes so fed up that he puts John Bell Hood in charge, and Hood, as he always does, immolates the army and refuses to evacuate the civilians. And Sherman’s like, what are you doing, bud? I’m giving you every chance to get out of here, and Hood won’t take it. And so, I think the Confederacy would have been better off leaving Joe Johnston in charge, because more of Atlanta might have been saved if it had just been surrendered the way Vicksburg had been. But John Bell Hood won’t do that, and so Sherman says, well, I guess I have a green light to light the torches, because you’re not going to respect that I told you to get out.

And so, yeah, I think it’s really interesting. They mirror each other for the first time in the war, where it’s the delaying action retreat that Lee has to do, which is Joe Johnston’s forte. And I think they’re communicating on that level. Lee surrenders before Johnston, of course, in April 1865.

And they’re in correspondence there too. There’s some thought that Lee’s army could turn south rather than out toward Appomattox and try and join Johnston’s army. It just doesn’t end up being feasible. But they do have a working relationship at this point. Though I don’t think anyone considered Johnston to be even half the soldier Robert E. Lee was. But he was probably the next best commander that Confederates had in 1864, ’65. He’s not nearly as good as Lee. He keeps getting these really important commands because he’s clearly the second most capable general that the army has.

He’s really understudied. It’s really interesting. It would be interesting to see a dual biography of those two guys, but Craig Symonds’ work is still phenomenal. So, we don’t necessarily need brand new Joe Johnston stuff, but they’re in a really interesting mirror action through the summer of 1864.

John Heckman: You said how Jefferson Davis trusts Robert E. Lee. This is something else that a lot of people may not realize: Because Lee’s backed up where he is, he can be in constant contact with Davis. He’s not that far away and they have this trusting relationship. Can you discuss that line of communications between those two, that they’re keeping each other abreast of what is going on on both sides, not only in Petersburg, but also in Richmond?

Cecily Zander: Yeah, they are in constant contact. In the summer of 1864, Braxton Bragg is also serving as Davis’ chief military advisor, so he’s just hanging out in the Confederate White House. And that’s probably where Bragg should have been from the beginning.

He’s almost a Halleck-like figure. Better to put him in a staff role than actually have him on the battlefield. So, they’re in constant communication. But what you have to say about Jefferson Davis here is Davis’ instinct was always to meddle, to try to be the one that set the plan, to try and actually design Confederate grand strategy.

But when it came to Robert E. Lee, he kept his nose out of it because he knew that Lee could do it on his own. So Lee is the one guy Davis will not meddle with. And so, they’re in cordial, constant communication, conferring about what’s going on, but Davis is always going to defer to Lee in terms of, what do we need to do? What’s going on here? I trust you that you’re not going to let Grant’s army march into Richmond. But, you know, it’s that summer when we get to 1865, the spring, when Lee’s sending a letter like, I can’t hold them back anymore. You better get out of the city. And Richmond is abandoned. But yeah, they’re in constant communication.

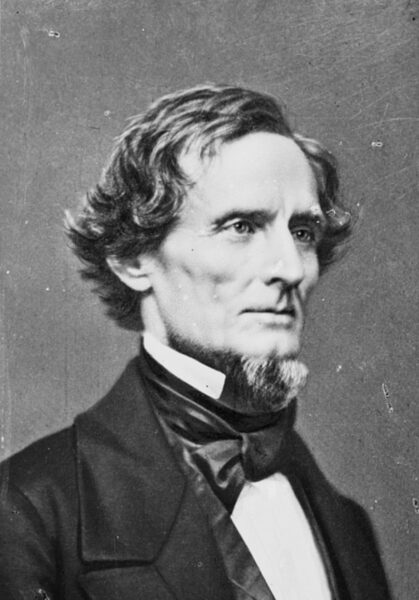

Library of Congress

Library of CongressJefferson Davis

What you have in this Overland Campaign into Petersburg, Grant and Lincoln have a phenomenal working relationship because Grant keeps his nose out of politics and says, I’m just going to do the war stuff. You can trust me to do that. And Lincoln says, that’s all I’ve ever wanted. Where were you in 1861? And with Lee and Davis it’s more like, Davis is outlining his thoughts all of the time. But he trusts Robert E. Lee to sift through that and take what’s most important. He doesn’t expect Lee to follow his every dictate. He rarely dictates to Lee about what Lee ought to be doing, which is rare for him, because his military background and his personality really made him a meddler in a way that Lincoln never was. Lincoln was not super confident in his ability. He grew into his ability as a military thinker and started to be more assertive about his ideas toward the end of the war.

But Davis from the beginning thought that he should be the one dictating strategy. He was going to try and lead the army onto the field at First Bull Run and they were like, no, maybe not. But with Lee, he doesn’t interfere or intervene in that way, though Lee is back in Richmond a lot.

Porter Alexander, of course, is wonderful on this. He’s spending a lot of time in Richmond as well. He’s the chief of Lee’s artillery at this point in the war. And so, a really important figure. His diary is wonderful through this Overland Campaign, siege of Petersburg period. And again, he doesn’t note any flagging or loss of confidence in Lee or the Army of Northern Virginia, either from Richmond or from the ranks.

But they’re trying to figure out this puzzle. Lee has not faced a siege. The world has never seen trench warfare. So, both Lee and Grant are innovating on that score as well. Like, what does this actually look like? And I was just telling a friend the other day, it’s amazing how quickly soldiers realize that the last thing you want to do when you’re in a trench is go over the top of that trench toward the other guy. I mean, Civil War soldiers realize this within in a matter of weeks and they start refusing to go. And so, you have that as well.

But back to Lee and Davis. I think that that trust develops. At various points, Lee offers to step down and Davis constantly refuses, says you’re the best person we’ve got, and I trust you to do this. It is to Davis that Lee says if this becomes a siege, I don’t know how long we can last, but I don’t know where Lee could have kept retreating to, right? The Union army’s goal is Richmond, and Petersburg is going to be the outlying suburb where you’re going to end up in that siege. And so, we don’t like to say in history anything’s inevitable, but I think Lee probably would not have written a letter saying if this ends in a siege, it’s over if he didn’t think that was a real possibility. He just didn’t have the solution or the resources to break out of that situation. So, he and Davis just confer about what’s it going to look like and how long can we hold out. And again, it’s that holding out. It’s that, let’s get to November and see where things go. Can we break Union morale and convince them that this war is unsustainable?

And Lee always inflicted incredibly high casualties on Union armies. That’s what makes him such an annoyance to the Union and beloved by the Confederates is that no Union general is as bloody as when they face anyone else except Robert E. Lee. And they all get bloody when they run into Robert E. Lee. Which is great for the Confederacy.

He embarrasses Union commanders. And that’s why he has the green light to be so aggressive. In a war where the Confederacy really should have fought on the defensive, and that was Davis’ plan, Lee is always given an exemption from Davis’ grand strategy.

You can be aggressive. You can set your own military policy, use your own tactics. And it works out in almost every case for Lee and Davis. So, they have this really harmonized relationship where they respected each other. Davis does not achieve that with a single other one of his highest-ranking general officers.

In fact, he spends a lot of the war just arguing with all of them. So, he’s not the greatest commander in chief or president in that regard, but he was president of a nation that spent its entire existence in the universe at war with a much more powerful, stronger opponent trying to establish its independence.

So, he was up against the wall.

John Heckman: Do you think this summer of ’64 is harder for historical memories simply because it’s not what we see in paintings, the grandiose battle lines and open-field warfare? Do you think that’s why when we are looking at popular history with Petersburg or popular books that come out that sometimes the people off the street don’t really tend to notice them as much as a book about Antietam or a book about Shiloh because it’s not that kind of traditional way of thinking of Civil War battle?

Cecily Zander: There’s not the maneuver. We’re not going to discuss why the 15th Virginia was moved from here to here at the Wilderness, but that’s what people really love to think about. Those are the things they love to dig into. And at Petersburg, the question would be, why did they move 200 yards down the trench? That’s not really as interesting. What you have in the trenches of Petersburg is an incredible fertile ground for social history, for gender history, for all kinds of these other questions, but not necessarily the military topics that I think popular readers gravitate to.

Of course, there’s ways to combine those. I find it really fascinating. Part of me wonders, having been to northern France and Belgium and seen the battlefields of the First World War. The United States has these—and I’m sure you’ve seen them, John—like huge World War I monuments that Dwight Eisenhower picked out the spaces for, which was convenient because he knew the territory of northern France incredibly well by the time he got there. That was weird. But there are these remarkable monuments, four or five times as large as the biggest Civil War monuments you’ve ever seen. And I don’t know how many Americans would ever go to look at a World War I monument. And when I was standing there, seeing them, I was just thinking, this is such a forgotten war.

And I wonder if part of it is because it does not have that cachet of the set-piece battle. World War I is incredibly difficult to read about and study. And the tour that I was on, people were just depressed by the end. They were like, what do you mean 600,000 people died at Verdun? And then there was going to be another war 20 years later over the same territory and ground.

And it was like, yeah, it’s really, really difficult. This advent of modern war period, when you don’t have these major battles going on. And it’s always shocking to my students when I show them pictures of Petersburg once the trenches are abandoned. I show them the picture and I say, where do you think this is from? And they almost always say World War I. And I wonder if there’s a kind of relationship there. It’s like this kind of warfare is seen as so tragic in a way. So slow, so uninteresting. That in a kind of military aspect that it’s just not written about as much.

Of course, there are wonderful books about Petersburg and we should shout out A. Wilson Greene here, especially. There’s phenomenal work going on Petersburg, but it’s just slower. The day-to-day doesn’t look all that exciting or interesting. But we should also remember that if a soldier fought in every major battle in 1863, in the Army of the Potomac or the Army of Northern Virginia, you were fighting for nine days. Which means the other 356 days, you were sitting in camp or maybe marching somewhere. It’s not that different from sitting in a trench. They were just sitting in a field. But we have those exciting battles in between. And so, yeah, there’s books about the Battle of the Crater, and there’s books about Fort Stedman, and there’s books about the initial breakthrough at Petersburg.

But the day-to-day history of life in the trenches, I’d love someone to write that book. Because I think it’s a very, very rich and fertile way to especially do comparative history. But if Americans don’t remember Petersburg, I think it would also explain in many ways why they perhaps don’t remember World War I either.

These wars that are seen as aberrations in the norm. And that’s what you said, the Civil War is so interesting, some of it seems so Napoleonic and so exciting in that way, and then some of it seems so modern when you get to the end. It’s like, in 1864, this summer, when we get to Petersburg, it’s like the war cracks open and you look at the pre-modern and modern portions of the war in some ways. It’s so interesting. And for soldiers, I imagine it was difficult to comprehend. You go from being these marching mobile armies to being these stagnant sitting forces. I mean, that’s why a bunch of Pennsylvanians get so bored that they look at the Confederate line two miles over there and say, we can dig a tunnel. And it goes all the way up to Ulysses S. Grant and he’s like, ah, why not? They’re not doing anything else. Yeah, they might as well. What else are Pennsylvanians good for, right? Mining. Let them dig.

John Heckman: Well, thanks, Cecily. I’m a Pennsylvanian. What are you trying to say?

Cecily Zander: I’m a Penn State grad.

John Heckman: It’d be an interesting comparative history of a sociological look at it. And you being a Civil War historian and me being a First World War nerd, I think we have the potential to discuss those kinds of things. Because you’re absolutely right. You’re going from these major campaigns, like the Overland Campaign, and into Petersburg, and it’s an alien way of looking at warfare to most of these guys.

And you have the same thing in 1914 into 1915. And they’re like, what are we doing? And I’m sure the Army of Northern Virginia is like, yeah, it’s this or we go into the open field again like in the Overland Campaign and just suffer another how many thousand losses.

Cecily Zander: Right. What I’ve always been interested in, as I was mentioning, so many Civil War soldiers so quickly start refusing to attack over the top of these trenches. You don’t see that in World War I to the same degree. You might see like individual soldiers hold back, but oftentimes they do go forward.

And I’ve always wondered if this has to do with the fact that we have in the United States citizen armies. Where soldiers put themselves as citizens first and soldiers second. And so, they maybe feel they can assert more agency and saying, I’m actually not going to go forward. Whereas European armies’ conscripts, they feel like they don’t have a choice. Because there doesn’t seem to be quite as much full stop, like full scale refusal to go over the top in the First World War, as you see almost a few weeks into the siege of Petersburg in the Civil War.

And I wonder if that also says something about the different kinds of societies that are fighting these wars. And of course, when the Americans arrive in France and the French and the British army say, okay, we’re going to integrate you. And it’s nice to meet you, General Pershing. You’re not going to be in command of your own army. And Pershing’s like, no, I will be. Thank you. I’ll work with you guys, but no, I’ll be in charge of my army. They weren’t sure how these volunteer U.S. soldiers were going to mesh with these professional European armies. I think I’ve always been interested in that question, and increasingly so, as I’ve thought about it.

But, yeah, the civilian citizen armies of the Civil War treat the trenches quite differently than their European counterparts will about 50 years later. We don’t often think of Europeans paying much attention to American military history. Because American soldiers would go to Europe throughout the 19th century to observe European warfare.

The U.S. Army loves France, they model everything on France, even a lot of their terminology. But at the beginning of World War I, when the Germans and the Belgians and the French and the British start to dig in, are they saying anything about the American Civil War? Or did they have no idea that they’re replicating conditions that had existed 50 years previously?

I would love to know that.

Cecily Zander is assistant professor of history at Texas Women’s University and author of the recently published book, The Army Under Fire: The Politics of Anti-Militarism in the Civil War Era (Louisiana State University Press, 2024).

Cecily Zander is assistant professor of history at Texas Women’s University and author of the recently published book, The Army Under Fire: The Politics of Anti-Militarism in the Civil War Era (Louisiana State University Press, 2024).